6.4 Canada ’s Preparedness for Low-Carbon Growth: Detailed State-of-Play – Investment

Framing the Future: Embracing the Low-Carbon Economy

Investment

A transformation to a global low-carbon economy like the one envisioned hinges on mobilizing financial capital and delivering it where needed. At stake is the development of LCGS and their economical, profitable, and complete deployment domestically and globally — as well as the related environmental benefits. The emphasis on low-carbon spending was first evident as a response to the global recession through “green stimulus” funding, signalling that a green economy was a source of future growth. Investment and financing figure prominently in low-carbon growth plans, covering both the scale of investments required and the steps needed to unlock the necessary capital.230

Investment in LCGS is a leading indicator of potential shifts in the carbon or emissions intensity of an economy. LCGS investment includes public or private expenditures, or a mix of both. These expenditures may target specific LCGS segments like efficient vehicles or renewable energy, focus on infrastructure deployment, or focus on a particular stage of innovation. What follows is an overview of low-carbon investment across the globe. We next explore recent investment trends in Canada and assess their implications for the low-carbon transition.

PROFILE IN BRIEF

The world is witnessing a growing investment in low-carbon goods and services. The upward trend in world exports of “green” goods as a proportion of general merchandise exports began in 1990, posting higher growth rates than general merchandise exports overall.231 Investments in clean energy alone show significant gains. Since 2004, global new investment in renewable energy has increased roughly five and a half times.232 By way of rough comparison, annual investment in oil and gas increased four-fold between 2000 and 2011, not accounting for inflation.233 Strictly comparing investments related to electricity, in 2010, $185 billion was invested in electricity generation from small- and large-scale renewables with an additional $46 billion in large-scale hydro investments (roughly $230 billion in total).234 Combined, this exceeds the total 2010 investment in fossil-fuel plant capacity ($217 billion). Consideration of the net investmentz in fossil-fuel plant capacity ($155 billion) further increases this difference. Despite the global economic slow-down, investment in LCGS is growing rapidly.

Public investment in clean energy has been a key driver of recent LCGS growth. The global financial crisis was an opportunity for nations to sustain and expand low-carbon investment via economic stimulus. Twelve members of the world’s major economies committed a collective $192 billion in government stimulus related to clean energy.235 Many devoted significant shares of their economic stimulus packages to fostering a “green recovery” with South Korea leading the way at 80%, followed by the EU at 64%, China at 38%, and Norway at 30%.236 The green component of Canada’s economic stimulus was a modest 8.3% and primarily focused on low-carbon power, including nuclear energy, energy efficiency, and research.237

In spite of fiscal pressures, public investment in LCGS remains strong, with investments by emerging economies poised to outstrip those of their industrialized counterparts. The U.S., despite successive budget cuts in its recent federal budgets and a downward spending trajectory, continues to invest in low-carbon energy as part of its economic recovery,aa and is ranked third globally in terms of attracting clean energy investment. 238 In Canada, LCGS growth continued during the recent financial crises, in part through initiatives by certain provinces (e.g., growth in solar PV capacity stemming from Ontario’s Green Energy and Green Economy Act)239. The scale of investment occurring in emerging economies is remarkable. By sheer magnitude, China is unparalleled in its level of investment in renewable energy – with a total investment of $48 billion.240 In fact, 2010 marked the first time in which renewable energy investments by developing economies exceeded that of industrialized economies ($71 billion versus $69).241

Private sector investment in low-carbon is also growing, more recently induced by public investment. Between 2004 and 2010, venture capital for renewable energy technology development saw an average annual growth of 36%.242 Over the same time period, equipment manufacturing for renewable energy saw substantial annual growth as well — 45% for private equity expansion capital, and 87% in public markets.243 According to forecasts by the World Economic Forum private investment in renewable energy and energy efficient technologies could amount to $445 billion in 2012 and $594 billion in 2020.244

LOW-CARBON PREPAREDNESS

Investment, whether low-carbon or otherwise, closely relates to innovation. Investment in each phase of the innovation process plays a key role in enabling growth and ensuring that Canadian firms remain competitive in a global low-carbon economy.

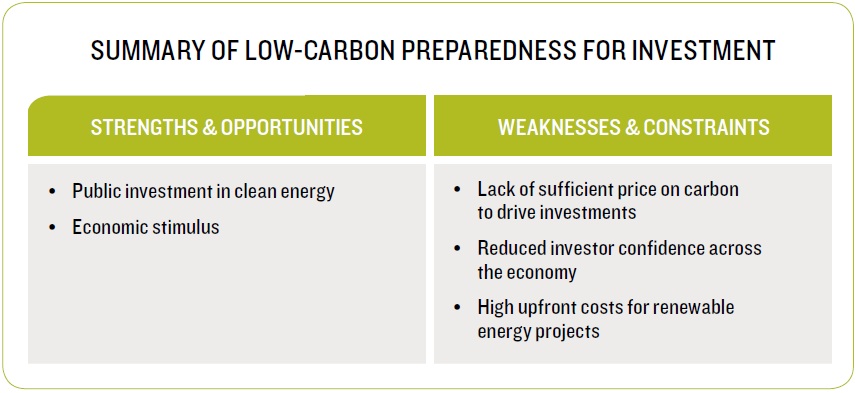

When it comes to low-carbon investment, our assessment focused on four indicators of preparedness: (1) LCGS investment relative to overall investment spending in Canada, (2) the nature of investment in lowcarbon innovation, (3) alignment between public investment and GHG emissions abatement, and (4) investor confidence in domestic LCGS markets.bb

Data and information related to baseline and forecasted public and private low-carbon investments in Canada is limited. The data and information that exist preclude a comprehensive analysis. Gaps in baseline information relate to existing data collection systems, which were not designed to permit the separation of low-carbon portion from the total. Despite data and information deficiencies, some observations are possible.

Economy-wide investment in non-residential structures, machinery and equipment (i.e., commercial products) provides a measure of the degree to which Canadian businesses are renewing capital assets and updating (and possibly adapting) technology to remain competitive. In Canada, such investment has averaged $234 billion annually over the past decade, 81% of which has been private investment.245 Spending on machinery and equipment alone accounts for an average of approximately $137 billion (58% of spending) per year.246

Based on a review of federal and provincial programs that include a significant low-carbon focus in their funding allocation criteria, we estimate that public and private investments prompted by these programs amount to approximately $5.7 billion per year.247,cc These investments are predominantly targeted at commercial products including machinery and equipment. Comparing this figure with the previously noted $118 billion annual investment in machinery and equipment suggests that Canadian low-carbon spending as a proportion of overall capital renewal is modest, in the range of 5%. The programs we considered in developing this estimate include those available through federal granting agencies, federal research agencies, the Program for Energy Research and Development, the ecoEnergy Technology Initiative, the Clean Energy Fund, Sustainable Development Technology Canada’s two funds, and 24 provincial climate change technology investment programs. Our estimates included both public and private investments that were motivated through these programs, but in many cases only partial funding data was available.dd

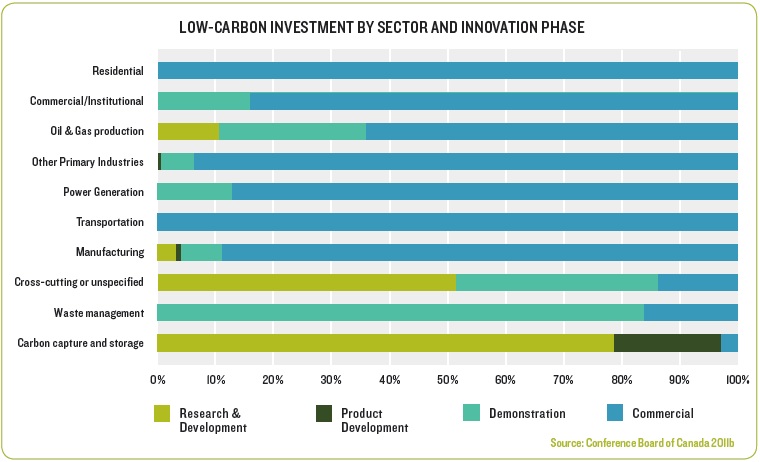

Working from this same data set we disaggregated investments by sector and innovation phase, as set out in Figure 18. This exercise illustrates three things. First, residential, commercial/institutional, and transportation sectors almost exclusively invest in already-commercial products and services. Second and not unexpectedly, carbon capture and storage investments focus on R&D and product development with the aim of overcoming cost and efficiency barriers and reducing technological risks related to its application. Third, product development — typically the purview of private-sector activity — is not a major focus of government-led investment programs. Overall, there is a heavy emphasis on investment in products that are already commercially established with much lower levels of investment in R&D, product development or product demonstration.

Figure 18

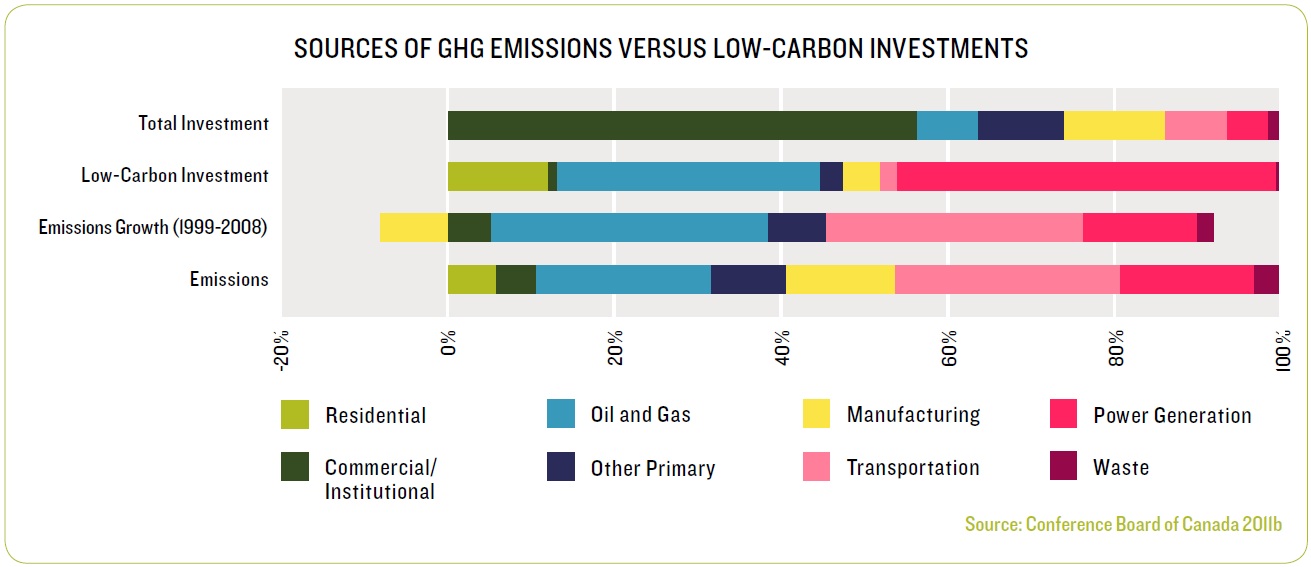

Figure 19 shows the shares of emissions and growth in emissions over the past 20 years for eight sectors, and their respective shares of total and low-carbon investment from the sample of government programs described above (excluding in-house R&D). Because available data sources do not capture investments that are made outside of those programs, what’s shown below understates the total. Although simplistic, such comparisons of Canada’s GHG emissions with low-carbon investments by sector can help identify whether Canada is making investments in sectors facing the greatest emissions challenge, thereby improving competitiveness for those sectors as well as other sectors that purchase their goods or use their services.

Figure 19

THE ANALYSIS RAISES A FEW QUESTIONS :

Is the scale of low-carbon investments by government directed at transportation less than it should be? Several measures targeting transportation emissions are low cost, which partially accounts for the low investment levels in that sector. For example, most provinces have programs in place to encourage consumers, industry, and government departments to purchase fuel-efficient vehicles and adjust practices to reduce fuel consumption. Québec pioneered the use of speed-limiting devices for heavy-duty trucks, and other provinces are following suit. Finally, the federal government has imposed tailpipe emissions standards on new vehicles, a step that is expected to reduce GHG emissions with a relatively modest level of investment. As low-cost opportunities to reduce transportation emissions are exhausted, high-cost measures and related investments will be necessary.

What accounts for the drop in emissions from manufacturing where emissions have declined in spite of a very low level of government support as compared to other sectors? Two reasons stand out. One is regular investment in machinery and equipment that is undertaken to modernize and remain competitive, over and above any response to government initiatives. The other is the impact of capital cost allowances and investment tax credits that are not directly measured in program investments.

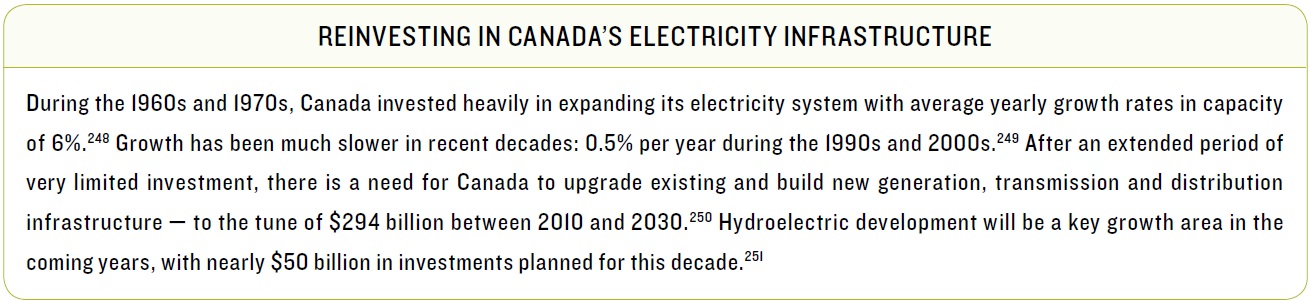

Is the scale of low-carbon investments by government directed at power generation more than it should be? This sector’s share of low-carbon investments outweighs its share of emissions, and two factors could help explain this. First, we allocated half of investments in carbon capture and storage to power generation despite its uncertain future benefits to the sector. Second, government low-carbon investment programs have focused on small-scale renewable electricity generation technologies, primarily wind power and solar power. The low-carbon investment in this sector is even higher than shown in the figure since retail support programs (such as the FIT program in Ontario) generate investments that we don’t capture in these data. Regardless of the role of electrification in the low-carbon transition, significant reinvestments in Canada’s electricity infrastructure are foreseeable (see Box 11).

Box 11

Signs of investor confidence in domestic LCGS markets provide mixed messages. In the past five years, renewable energy projects in Canada have received over $16 billion of asset financing.252 Much of the financing has gone to on-shore wind, an energy application that’s attractive to investors due to its costcompetitiveness and relatively low technological risk. Venture capital activity in Canada appears healthy: as recently as 2011, Canada ranked fourth behind the U.S., China, and the U.K. in terms of investments in cleantech.253 Much of the VC investment activity in cleantech takes place in Ontario, with investment in the province accounting for 48% of total Canadian investment since 2005.254 Recent events suggest a drop in investor confidence, however. Despite $742 million in federal and provincial subsidies and project costs remaining within the expected range, industry partners terminated the Pioneer carbon capture and storage project in Alberta in April 2012 because “the market for carbon sales and the price of emissions reductions were insufficient to allow the project to proceed.”255 As part of its plan to “refocus strategies and activities,” Ottawa-based Iogen abandoned a development project for a biofuel plant in southern Manitoba.256 Growing and maintaining investor confidence in Canada’s LCGS markets is key to the low-carbon transition (see Box 12). Public incentives, regulatory stringency, and a climate regime characterized by transparency, longevity, and certainty stand out as factors with the potential to do just that.257

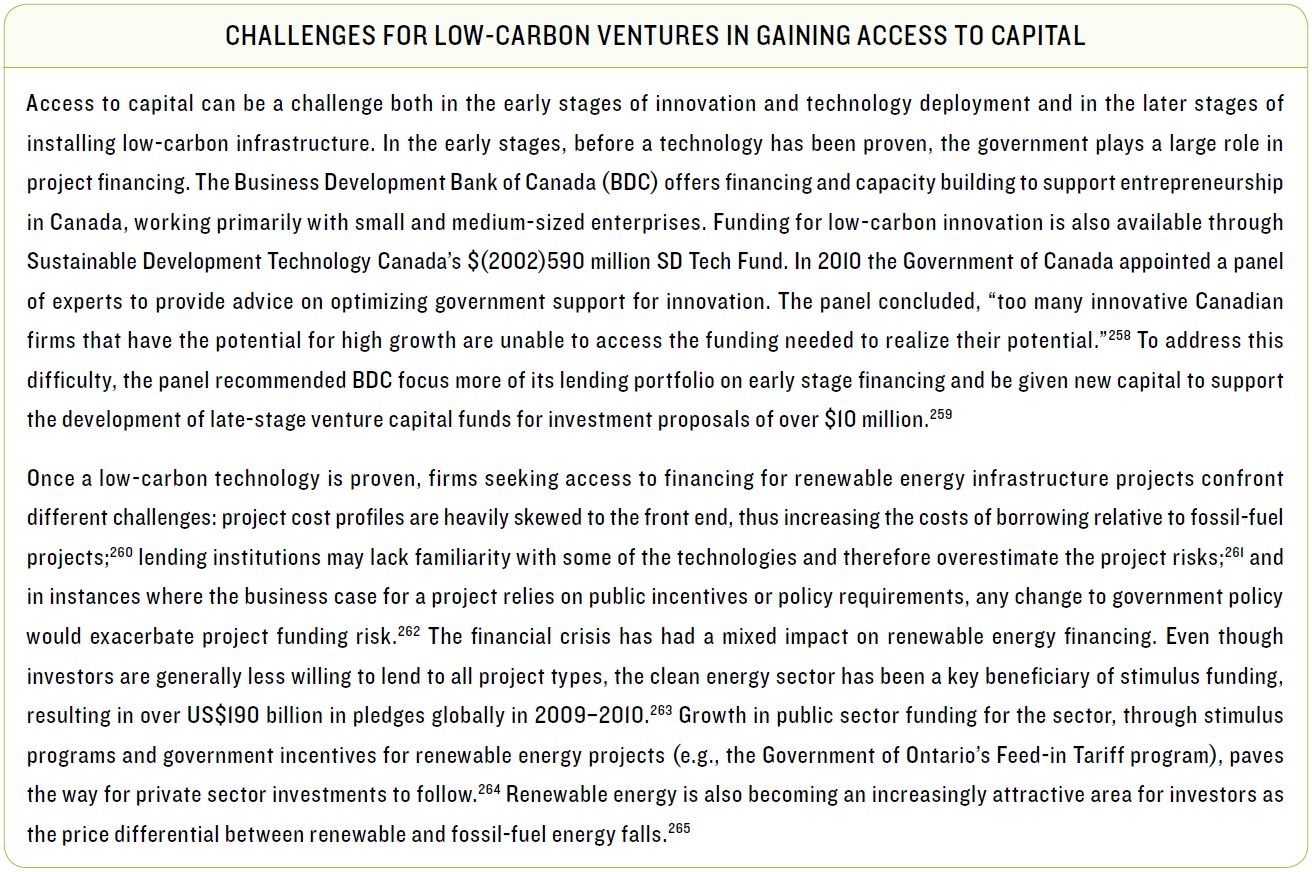

Box 12

Table 11

[z] Net investment excludes capacity being brought on-line to replace existing capacity which is being retired.

[aa] Close to 75% of all federal U.S. “clean energy” funding over the 2009–2014 period is directed toward cleantech deployment and adoption (e.g., renewable energy). It is estimated that the U.S. government will spend in excess of $150 billion on cleantech programs in the 2009–2014 period, more than 3 times its expenditure from 2002–2008. However, significant cuts were experienced over 2011, and it is expected that cleantech spending will be reduced to half the 2011 investment in 2012 with further reductions to come. Approximately one third of the total spending over this period derives from the American Recovery and Reinvestment act of 2009 (ARRA), which, along with a number of time-limited incentive programs, is coming to an end in 2012 (Jenkins et al. 2012).

[bb] The discussion in this section draws primarily from a research report prepared for the NRT by the Conference Board of Canada (2011b), available upon request.

[cc] This represents a low-end estimate that is considered to be representative of the scale of investment, but not precise. Data gaps for some programs were noted and partnering funding was not consistently available.

[dd] Conference Board of Canada (2011b) provides a complete list of the programs included in this assessment.

[230] Baer and Barnes 2010

[231] Bora and Teh 2004; as cited in OECD 2005b

[232] United Nations Environment Programme and Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2011

[233] International Energy Agency 2011a

[234] United Nations Environment Programme and Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2011

[235] The Pew Charitable Trust 2011

[236] Robins, Clover, and Singh 2009

[237] Robins, Clover, and Singh 2009; National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy 2010

[238] The Pew Charitable Trust 2011

[239] Canadian Solar Energy Industries Association 2010

[240] United Nations Environment Programme and Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2011

[241] United Nations Environment Programme and Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2011

[242] United Nations Environment Programme and Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2011

[243] United Nations Environment Programme and Bloomberg New Energy Finance 2011

[244] World Economic Forum 2010 as cited in ; Sustainable Prosperity 2010

[245] Statistics Canada 2012e

[246] Statistics Canada 2012e

[247] Conference Board of Canada 2011b

[248] Baker et al. 2011

[249] Baker et al. 2011

[250] Baker et al. 2011

[251] Tal and Shenfeld 2011

[252] Roberts 2011

[253] Michael 2011

[254] Michael 2011

[255] Project Pioneer 2012

[256] Royal Dutch Shell and Iogen Corporation 2012

[257] Deutsche Bank 2009

[258] Panel on Federal Support to Research and Development 2011

[259] Panel on Federal Support to Research and Development 2011

[260] World Economic Forum 2011a

[261] Justice 2009

[262] Justice 2009

[263] World Economic Forum 2011a

[264] Justice 2009

[265] World Economic Forum 2011a