6.4 Canada ’s Preparedness for Low-Carbon Growth: Detailed State-of-Play – Innovation

Framing the Future: Embracing the Low-Carbon Economy

Innovation

Innovation is a tool for increasing productivity and competitiveness; it is also a building block of many low-carbon growth plans (see Box 8 for a definition). Innovation can close the gap between the lowcarbon technologies of today and the low-cost, high-performance — breakthrough — technologies that are needed for the future. Why is accelerating low-carbon innovation key for Canada? In today’s global economy, Canadian firms are up against counterparts facing lower labour costs199 and, to an extent, greater access to capital and policy certainty. Rather than trying to compete on “last generation” technology by cutting input costs, a focus on innovation can enable the rise of Canada’s low-carbon goods and services (LCGS) sector — a segment of cleantech — in global low-carbon value chains. Innovation is also the only way to enhance environmental performance of traditional industries despite increased use of natural resources, including energy.

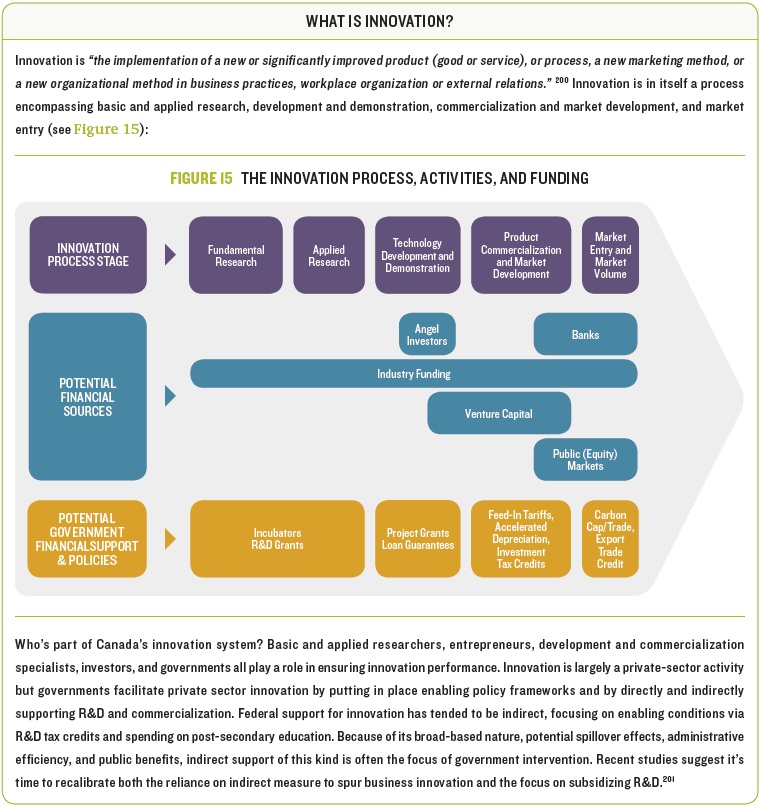

Box 8

PROFILE IN BRIEF

Canada’s innovation performance has been subject to discussions for decades. Economic, policy, and benchmarking studies all arrive at the basic conclusion that Canadian business innovation is underwhelming relative to that of its competitors.202 Several explore root causes of this chronic issue and recommend ways to narrow the gap between levels of support for business innovation and commercial success.t Since lowcarbon innovation is a subset of innovation at large, key characteristics of Canada’s innovation system are worth noting.

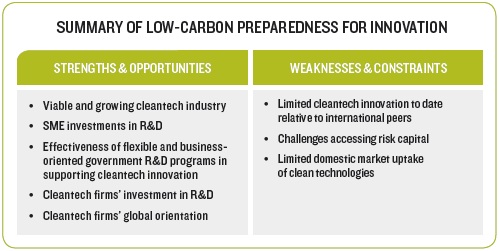

Overall, the strengths and weaknesses of Canada’s innovation system sum up as follows. Canada focuses most on and succeeds at basic science and research, and adapting (already) commercial products to meet industry requirements. Canada is less effective than its OECD peers in product demonstration and in the transition to commercial scale and market development.203

Canada’s performance in early stages of innovation — idea generation, basic and applied research, laboratory demonstration, and related academic support — compares well to OECD peers’.204 Within the OECD, Canada offers the second highest level of support to R&D at 0.24% of GDP. Over 90% of R&D support is provided as tax credits (such as the long-standing Scientific Research and Experimental Development program).205 Public investment in universities and colleges is also notable. At approximately 0.7%, Canada ranks second highest among OECD peers in higher education expenditure on R&D (HERD) as a proportion of GDP.206 The high quality of Canada’s education system overall — and specifically the high quality of math, science, and engineering education and management schools — provides a strong base for innovation in Canada. In contrast, private sector or business expenditure on R&D as a percentage of GDP is below the OECD average (see Box 9).

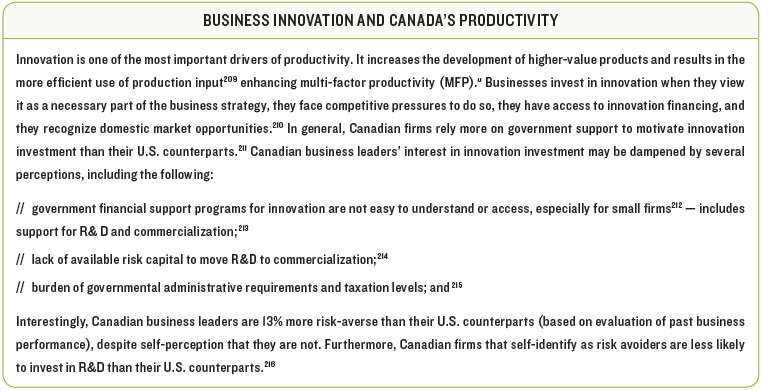

Box 9

But it is no secret that Canada is not reaping the economic benefits of public R&D investment as much as it could be.217 Canada is strong in science and engineering R&D aspects of the innovation cycle but weak on taking those ideas to market.218 Three reasons for this are apparent.219 The first is access to risk capital (venture capital or angel investors) — the primary sources of funding for the transition from a demonstrated product to a share of the market. The creation of Sustainable Development Technology Canada (SDTC) was a federal response to bridge funding gaps preventing products’ transition from demonstration to commercial success. British Columbia and Ontario have both established funds to co-invest in new technologies alongside venture capital firms. The second is actual market development. Canada has a small internal market with limited opportunities to demonstrate new technologies, inadequate government procurement and inadequate adoption of domestic technologies.v As well, a large percentage of innovations occur upstream from the end user. This not only runs the risk that Canadian firms will produce innovations that the market won’t accept, but it also supports the tendency that firms will import technologies or machinery and adapt them.220 The third is fragmentation among key players. A lack of efficient and targeted collaboration between Canadian universities and businesses has hindered the translation of academic knowledge into viable commercial applications.221

LOW-CARBON PREPAREDNESS

In its simplest form, low-carbon innovation is about bringing products, processes, or practices to market that are better, cheaper, or more resource-efficient relative to conventional counterparts while reducing or eliminating GHG emissions. Such innovation takes place within firms in traditional industry sectors and is a major focus of firms in the “clean technology” or “cleantech” sector.w Because over 80% of Canada’s total GHG emissions stem from production, transformation, transmission, or final use of energy, low-carbon innovation tends to centre on energy.

When it comes to innovation, our assessment focused on three indicators of low-carbon preparedness: (1) market presence, (2) LCGS firms’ propensity to innovate, and (3) government support for low-carbon R&D. In describing low-carbon innovation much of the research and analysis covers cleantech at large, and so our discussion below refers to cleantech and low-carbon innovation interchangeably.

Relative to its competitors, Canadian cleantech innovation is weak. Canada ranked twenty-third of 26 countries evaluated regarding the sales of clean technology products in 2008, with Germany, the United States, China and Denmark leading the pack by a considerable margin.222 Globally, Canada ranked fourteenth in terms of the magnitude of clean technology exports and seventh in terms of imports.223

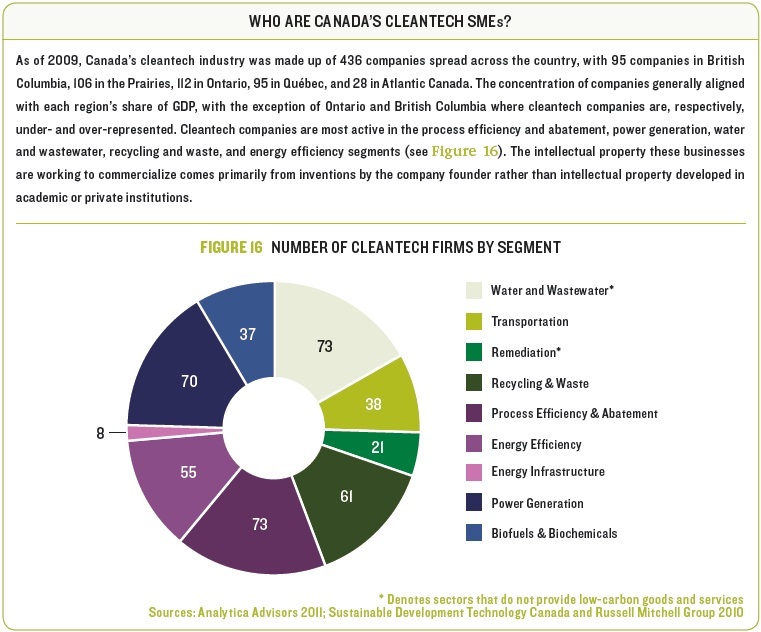

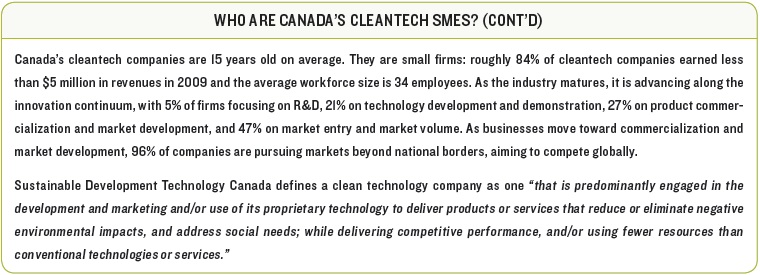

Yet Canada’s cleantech industry is a viable and growing contributor to the economy. Over eight in ten firms in this industry are small and mid-sized enterprises (SMEs),x reflecting its relatively young (15-year) age as an industry. In 2009, these 436 firms amounted to a $2 billion industry,y posting double-digit growth rates through the global financial downturn. Based on current and projected growth rates, Canada’s cleantech industry is on track to achieving $10 billion in revenue by its twentieth-year milestone, much like occurred with the aerospace and defence industry. A snapshot of Canada’s cleantech SMEs appears in Box 10.

Box 10

Canada’s cleantech industry is well positioned to become a globally competitive and innovative LCGS sector. The single greatest motivation for business innovation is competition.224 Absent a domestic market and despite a strong dollar, Canadian cleantech SMEs have ambitions to compete globally and take advantage of growth in emerging economies. Canadian cleantech SMEs are nine times more likely to export than Canadian SMEs overall and far less reliant on export sales from the U.S.225 By implication, they will have to innovate to survive and could well do so. Canadian clean technology SMEs invest early and generously in R&D — and this is with pre-profitability dollars and during times of recession.

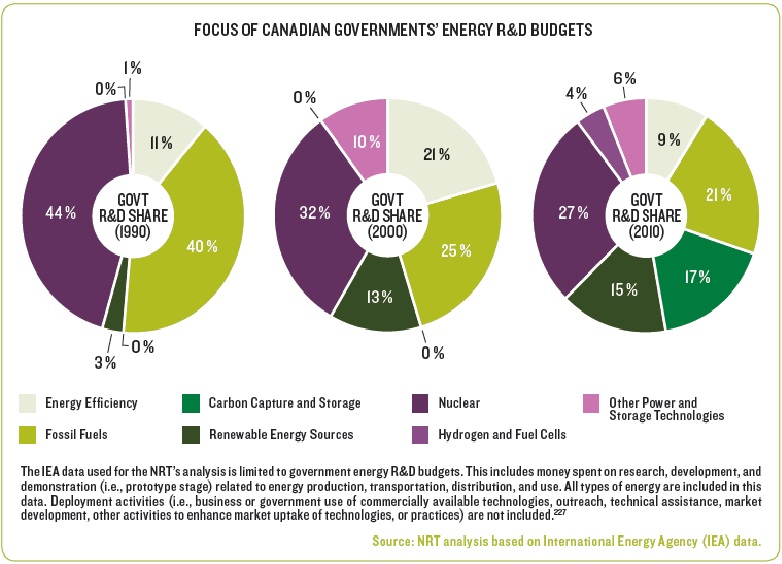

Canadian governments perform and support R&D with the potential to spur low-carbon innovation that, for the most part, aligns with cleantech firms’ needs. A look at three snapshots in time of Canadian governments’ R&D budgets targeting energy activities shows a shift from a heavy focus on fossil fuels and nuclear to an increasing share of renewable energy sources and carbon capture and storage (Figure 17). When it comes to the needs of cleantech firms specifically, strengths and weaknesses of federal R&D programs are apparent. Canadian cleantech SMEs have high regard for R&D programs that are business-oriented and don’t require multi-year collaborations with academia and large companies. These include the Scientific Research and Experimental Development tax-credit program, the Industrial Research Assistance Program, and Sustainable Development Technology Canada’s Tech Fund.226 The majority of federal R&D programs, however, present high barriers to entry for SMEs. Streamlining administration and approvals for federal R&D programs would increase their attractiveness to SMEs.

Figure 17

A final message from Canada’s cleantech SMEs was clear: enhancing domestic adoption of their innovations was necessary for Canada to benefit from public and private R&D investments.228 If unaddressed, the lack of domestic adoption and support could hinder export growth. For innovative clean technologies, international customers expect domestic references before making procurement decisions.229

Table 10

[t] See, for example, Council of Canadian Academies 2009; Ontario Chamber of Commerce and Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation 2012

[u] MFP is considered one of three principal factors that account for labour productivity growth. It is “a residual measure that captures all other factors that affect productivity. MFP reflects how effectively labour and capital are employed jointly to produce output” (Panel on Federal Support to Research and Development 2011).

[v] Domestic technology procurement and adoption by the public sector has been identified as an urgent issue by the Canadian Clean Technology industry (Analytica Advisors 2011). A federally commissioned review of Canadian R&D found that more government support was needed on the demand side to foster Canadian business innovation (Panel on Federal Support to Research and Development 2011). They recommended increasing public sector procurement of Canadian goods, services, and technologies,by expanding existing federal initiatives such as the Canadian Innovation Commercialization Program (Public Works and Government Services Canada 2012).

[w] Clean technology firms focus on developing, marketing, and/or using proprietary technology to deliver products or services that reduce or eliminate negative environmental impacts and address social needs while delivering competitive performance and/or using fewer resources than conventional technologies or services (Analytica Advisors 2011).

[x] In this report SMEs refer to companies having fewer than 500 employees and less than $50 million in annual revenues (Analytica Advisors 2011).

[y] The information on SMEs in this section is taken from Analytica Advisors 2011.

[199] Toronto Dominion 2011

[200] OECD 2005c, 2005a

[201] Panel on Federal Support to Research and Development 2011

[202] Conference Board of Canada 2004; Council of Canadian Academies 2009; Panel on Federal Support to Research and Development 2011

[203] Conference Board of Canada 2011b

[204] Government of Canada 2009a

[205] OECD 2010

[206] Niosi, Samarasekera, and Treurnicht 2008

[207] World Economic Forum 2011b

[208] OECD 2010

[209] Rao 2011

[210] Conference Board of Canada 2012a

[211] Deloitte & Touche LLP 2011

[212] Deloitte & Touche LLP 2011

[213] Ontario Chamber of Commerce and Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation 2012

[214] Deloitte & Touche LLP 2011

[215] Conference Board of Canada 2012a

[216] Deloitte & Touche LLP 2011

[217] Panel on Federal Support to Research and Development 2011

[218] Council of Canadian Academies 2009

[219] Conference Board of Canada 2011b

[220] Council of Canadian Academies 2009

[221] Panel on Federal Support to Research and Development 2011

[222] Roland Berger Strategy Consultants 2009

[223] Goldfarb 2010

[224] Jenkins 2011

[225] Analytica Advisors 2010

[226] Analytica Advisors 2011

[227] International Energy Agency 2011b

[228] Analytica Advisors 2011

[229] Analytica Advisors 2011