6.4 Canada ’s Preparedness for Low-Carbon Growth: Detailed State-of-Play – Governance

Framing the Future: Embracing the Low-Carbon Economy

Governance

Governance shapes a nation’s response to and management of the global transition to a low-carbon economy (see Box 13 for definitions). A transformative shift in policy direction and objectives — such as that required for countries to prosper in a low-carbon transition — requires vision and leadership above all else.285 Without exception, political leadership was necessary to propose, endorse, and embed the low-carbon growth plans where they exist.

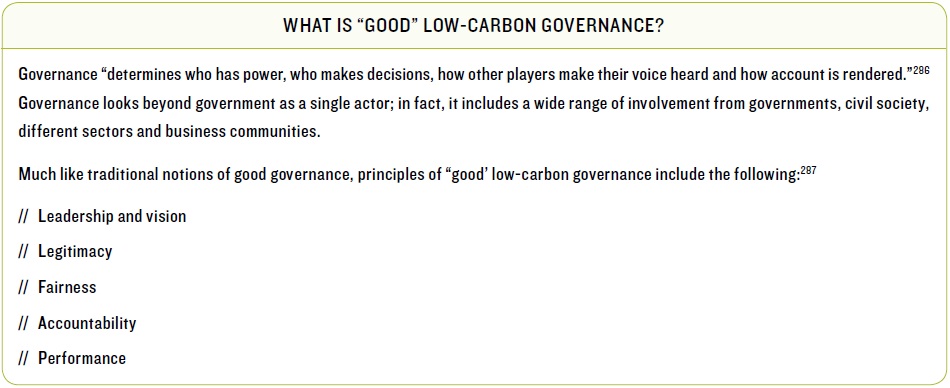

Box 13

Coordination among institutions at similar levels of organization and across jurisdictional levels is key. Mechanisms that facilitate engagement, co-operation, joint learning and information sharing all play a role.288 Canada’s federalist context combined with the need to integrate low-carbon growth across a number of policy areas makes a focus on governance solutions all the more important.

PROFILE IN BRIEF

Canadian federalism presents unique governance challenges. The federal government has regulatory control of interprovincial trade and international trade and commerce; other areas offer decentralization and delegation of authority to provinces, as with energy and natural resources. Yet other areas, such as the environment, are a shared responsibility. Divisions of power make tackling far-reaching policy issues a challenge in practice. Current structures governing energy and innovation are good illustrations of this.

Regulatory complexity and the cross-border nature of energy complicate achieving clean energy goals. The energy sector involves numerous actors and regulators. Canada’s power industry encompasses Crown corporations in some provinces, privately held utilities or both private and Crown corporations in others.289 Several provinces also include independent regulatory boards that set electricity rates and arms-length agencies that undertake long-term planning (e.g., Ontario Power Authority). The National Energy Board, as an arms-length federal agency, regulates international and interprovincial aspects of the oil, gas and electric utility industries. The nuclear sector is under federal government regulation through the Nuclear Safety Commission. Environmental regulation around energy-related developments is also a mixedjurisdictional issue.

LOW-CARBON PREPAREDNESS

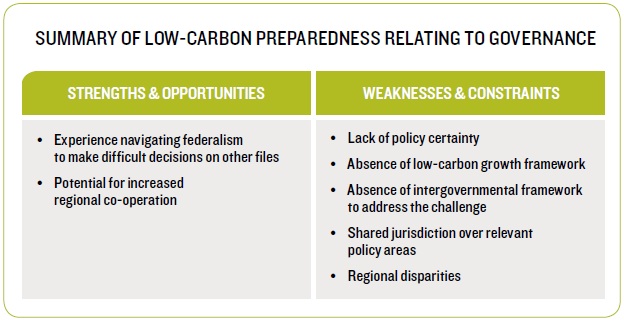

Previous NRT reports have discussed Canada’s governance performance in the low-carbon transition. Key conclusions related to weaknesses in Canada’s policy signals: a lack of a low-carbon growth framework; presence of medium-term GHG target but no systems to independently monitor and report on performance; and absence of a unified, national carbon price. What follows is a discussion focused on leadership and coordination.

Specifically, in assessing Canada’s low-carbon preparedness relating to governance, we looked at (1) opportunities and constraints to enhance leadership to set a low-carbon vision for Canada and follow through with it and (2) the extent to which existing mechanisms facilitate coordination on low-carbon issues.

Canada as a whole does not have a coherent climate change strategy or a low-carbon growth plan. The failure to bridge regional interests and perspectives over the past 20 years has resulted in a patchwork of uncoordinated federal and provincial actions to reduce emissions. Yet federations such as the European Union and Australia have managed to develop low-carbon growth plans. Federalism aside, four key factors are apparent for Canada: disparity in regional economic interests, a commitment to equitable burden sharing, a lack of capacity in institutional intergovernmental relations, and a polarized or unengaged public.

// Regional economic interests vary widely and differences in aspirations and identities surface immediately in discussions on energy and GHG emissions. Earlier in this appendix we covered regional differences in emissions sources and profiles. Provincial jurisdiction over natural resources can further distance regional interests in cases where gains in resource developments in one region are perceived to damage another. The public dispute in April 2012 between the Premiers of Ontario and Alberta over the net costs to Ontario’s manufacturing economy of Alberta’s oil sands development is an example of this.290 A renewed interest in a collaborative, pan-Canadian energy strategy represents an opportunity to orient the discussions toward low-carbon growth.291

// Burden sharing — internationally and domestically — while noble in intent is difficult to implement. Canada has a principle that “no region shall bear an undue portion of the cost” to meet emissions targets;292 however, consensus on how this ought to play out in reality remains elusive. Canada’s regional diversity in energy sources is a strength. This same diversity — and the diversity in the carbon intensity of the energy sources — has made discussion of climate policy and mitigation difficult due to significant variation in compliance costs across regions.

// Intergovernmental fora for discussion of environmental issues are lacking in stability and, in some cases, legitimacy. Gaps in stability refer for example to “participation rules that exclude first ministers” and processes that are “subject to change or dissolution in the face of changes in the underlying interests of actors.”293 Gaps in legitimacy become evident when actors choose to “opt out and work outside or around” existing processes.294 The National Climate Change Process (1998–2002) is a case in point: Ontario, Alberta, and Québec opted out of several ministerial decisions and remained unengaged at high political levels.295 Governance scholars have argued for the need to augment existing intergovernmental mechanisms in both substance and process to effectively address environmental issues.296 Although legitimate and effective institutions for intergovernmental relations exist, they have not been used well to make progress in tackling climate change. Institutions such as the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment, Canadian Council of Energy Ministers, First Ministers Meetings, and the Council of the Federation are mechanisms that could be improved to facilitate Canada’s low-carbon transition in a way that strengthens participation rules to guarantee appropriate decision making.

// Public opinion can help or hinder federal government leadership and, in the case of climate policy and low-carbon growth, public and media interest have inhibited political endorsement to date. Framing of low-carbon growth hasn’t aligned with Canada’s core interests. Due to Canada’s fossil-fuel energy wealth, a low-carbon growth plan is not seen to promote either energy security or economic expansion, but rather is seen to solely promote environmental merits. Public engagement on regional and national challenges and opportunities in the global low-carbon transition is a key step to steer the country toward a low-carbon economy (see Box 14).

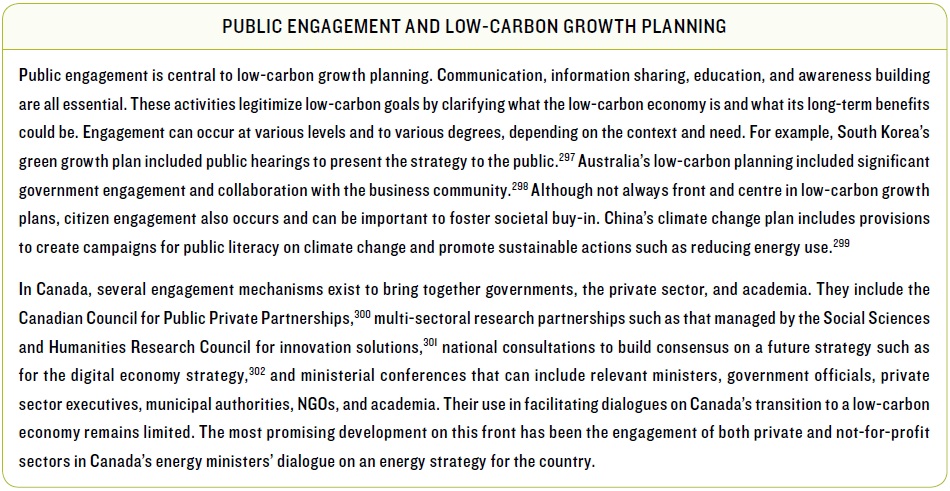

Box 14

Baseline deficiencies in coordination within and across government departments and ministries could stifle progress on low-carbon planning in the future. Horizontal coordination requires agreeing on objectives and co-operation mechanisms to achieve them. At a high level, departments (or even groups within a department) may be tasked with mandates that require the resolution of conflicting interests. In the absence of a “wholeof- government” sense of purpose, departments may ultimately work at cross-purposes. More commonly, “silos” exist within both federal and provincial government departments. Absent the appropriate tools to break down silos, effective communication and information sharing does not occur. This leads to inefficiencies at best and counter-productive efforts at worst. Perverse outcomes such as these are in most cases unintentional, resulting from a lack of clear leadership.

The market implications of gaps in leadership and coordination are significant. Simply put, key sectors of the Canadian economy lack the policy certainty or support to prioritize low-carbon investments. Instead, investors, firms, and households may postpone investment decisions or choose conventional options with known payoffs.

Table 15

[285] Meléndex-Ortiz 2011 as cited in; The Frederick S. Pardee Center 2011

[286] Institute on Governance 2011

[287] Graham, Amos, and Plumptre 2003; Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia 2012

[288] Corfee-Morlot 2009

[289] Centre for Energy 2012

[290] Mendelsohn ND

[291] Gibbins 2009

[292] Gordon and Macdonald 2011

[293] Gordon and Macdonald 2011

[294] Gordon and Macdonald 2011

[295] Gordon and Macdonald 2011

[296] Courchene and Allan 2010

[297] United Nations Environment Programme 2010

[298] ClimateWorks Australia 2010

[299] National Development and Reform Commission People’s Republic of China 2007

[300] The Canadian Council for Private-Public Partnerships 2012

[301] Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada 2012a

[302] Industry Canada 2010