Parallel Paths – 3.3 Canada Harmonizes with the U.S. on Climate Policy

This section explores the implications of Canada and the U.S. pursuing parallel climate policies with the aim of harmonizing on GHG reduction targets or on carbon price. This section does not include linkage scenarios, which are explored in the following chapter as possible tools to address the risks highlighted in this chapter.

As seen, Canada has already harmonized GHG emission-reduction targets with the U.S. as well as vehicle emissions standards for new cars and light trucks. Yet Canada has signaled its intent to phase out coal-fired electricity plants starting in 2015, independent of the U.S. Competitiveness has been cited as a key reason Canada should harmonize its climate policy with trading partners and specifically with the U.S. However, harmonizing with the U.S. is not straightforward. As we will see, Canada cannot easily achieve the same levels of emission reductions at the same carbon price as the U.S. Different approaches to harmonization therefore result in different environmental and economic outcomes.

ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS

Harmonizing Canadian climate policy with the U.S. generally reduces environmental risks for Canada, if the U.S. implements a similar cap-and-trade system. Harmonized 2020 targets in Canada and the U.S., with a carbon price in both countries, would lead to emission reductions in Canada. This action would, in turn, set the stage for deeper reductions in the long term. Harmonizing on carbon price with the U.S., by contrast, does not lead to the full, stated 2020 emission reductions due to differences in the cost of carbon abatement in Canada. A higher carbon price is required in Canada to achieve the same level of domestic emission reductions. So, Canada risks not achieving its targets if a harmonized carbon-pricing policy is pursued rather than a harmonized GHG-target policy.

ECONOMIC RISKS

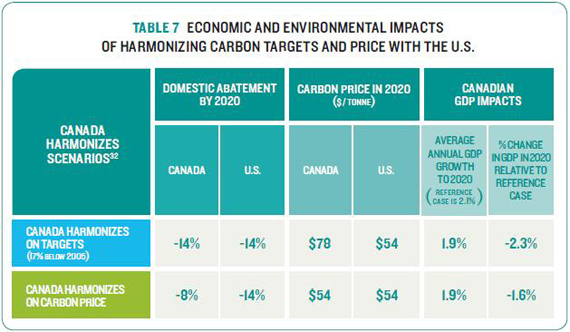

Economic risks to Canada of harmonization depend in large part on the nature of Canada-U.S. climate policy harmonization. Current federal government policy is to harmonize on targets. Our analysis below demonstrates that this approach requires a carbon price differential that could pose certain competitiveness risks. So, common carbon-reduction targets do not result in common carbon prices. Harmonization on carbon price tends to reduce economic impacts by addressing competitiveness risks, but does not eliminate impacts. And, as we illustrate in Table 7, it raises environmental risks of not achieving similar levels of emission reductions for the two countries. Our analysis shows that, overall, Canada’s own GHG mitigation policy and the resulting emission reductions in the Canadian economy are the single-largest determinant of economic impact in Canada.

HARMONIZING CARBON PRICES AND TARGETS

NRTEE modelling considered the environmental and economic impacts of harmonizing on targets and on prices in detail. Key results are set out in Table 7.

Differences between the costs of abatement in Canada and in the U.S. explain the results in this table. Setting matching targets with matching levels of reductions to be achieved will likely result in significantly different carbon prices — and they will be higher for Canada. With both countries achieving reductions of 14 % below 2005 levels by 2020 in terms of domestic emissions (the remainder — to get to 17 % below 2005 — is made up from international purchases of permits, which helps keep domestic costs down), NRTEE modelling suggests Canada would have a price of $78/tonne CO2e, while the U.S. would have a price of $54/tonne CO2e.

On the other hand, aligning carbon prices would result in different domestic reductions. For example, if Canada were to match the U.S. carbon price of $54/tonne CO2e, it would achieve only an 8 % reduction domestically — less than half its stated target — while the U.S. would achieve close to a 14 % reduction from 2005 levels. Matching price then, would impact Canada’s ability to achieve its emission-reduction targets. Canada would then have to look to other options to make up the shortfall to reach its 17 % target, such as access to international permit markets. There are costs to these options also, which we assess later.

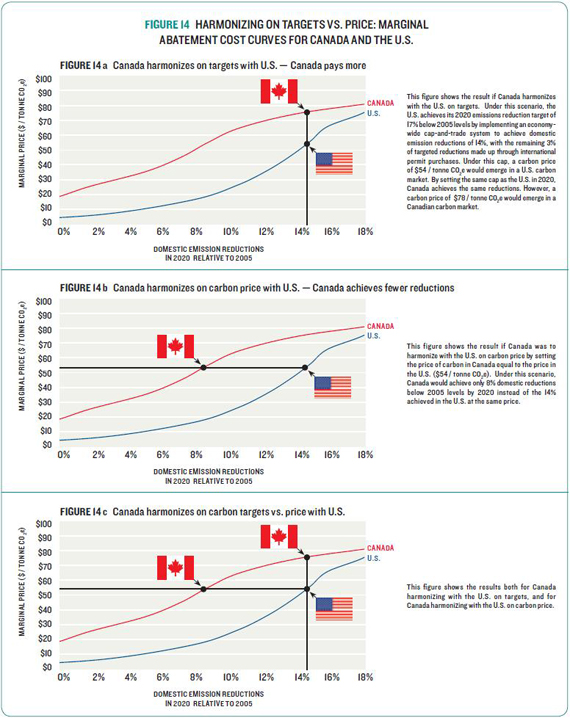

The challenges behind harmonizing on both carbon price and emission-reduction targets are illustrated in Figure 14. This figure is derived from original NRTEE modelling. The marginal abatement cost (MAC) curves shown in the Figure illustrate the incremental cost for reducing one tonne of CO2e emission. They can also be understood as the reductions that will occur as result of policy that imposes a price on carbon. At low levels of reductions, the Canadian curve is higher than the U.S. curve given the higher rate of emissions growth projected for Canada: if no policy to price CO2 was imposed, emissions in Canada would just increase. This result is broadly consistent with other economic analyses.33 Both cost curves begin to level off at higher marginal prices as the electricity generation sectors switch from coal to a range of low-carbon generation approaches. The differences between the Canadian and U.S. curves indicate that harmonizing on targets leads to different carbon prices while harmonizing on carbon price leads to different emission reductions.

Where Canada and the U.S. are positioned on the cost curves — i.e., the price of carbon and the corresponding level of emission reductions — is determined by the specific elements of policy design. The curves only include domestic abatement and do not account for elements of domestic cost-containment, which would reduce costs. Countries could use international permits or domestic offsets to achieve compliance with domestic targets at lower costs. Alternatively, they could limit the permit price using a safety valve. These forms of cost containment effectively avoid the steep parts of the cost curves associated with deep, high-cost reductions. The price of carbon resulting from the policy is therefore not only a function of the targets to be achieved but also the extent to which compliance mechanisms such as offsets or technology funds are allowed. We return to the trade-offs associated with these specific policy tools in Chapter 4.

SAFETY VALVE AND OFFSETS

- SAFETY VALVE is a cap-and-trade design mechanism to set a maximum permit price. By selling additional permits directly at this price, government can limit the magnitude of the market price of carbon.

- OFFSETS are emission reductions that are created outside any regulated system and sold to regulated emitters. Regulated emitters can use offsets, instead of permits, to comply with the carbon-pricing policy. Because emission reductions from changes in forestry, agriculture, or landfill gas practices are difficult to include under a cap-and-trade system directly, including these reductions as offsets can allow firms to take advantage of potentially lower-cost reductions in these areas, reducing the overall costs of the policy.

RISKS OF A CANADA-U.S. CARBON PRICE DIFFERENTIAL

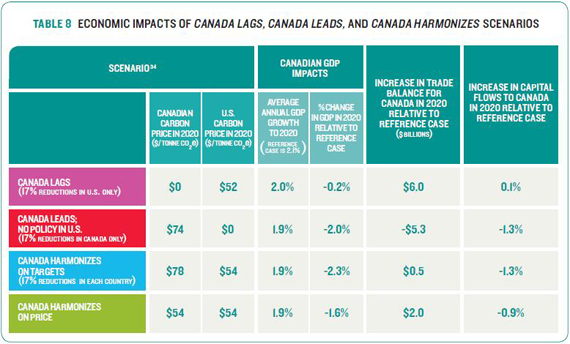

How significant are the risks of different carbon prices in Canada and the U.S. relative to other drivers of economic impacts? Table 8 illustrates GDP and trade impacts for different levels of carbon price alignment. The results show that a higher carbon price in Canada leads to decreased exports for Canada, with a larger price differential leading to a larger negative trade impact. They reinforce the idea that a higher carbon price for Canada creates competitive disadvantage. But overall macroeconomic impacts for Canada for both Canada Harmonizes and Canada Leads scenarios are very similar.

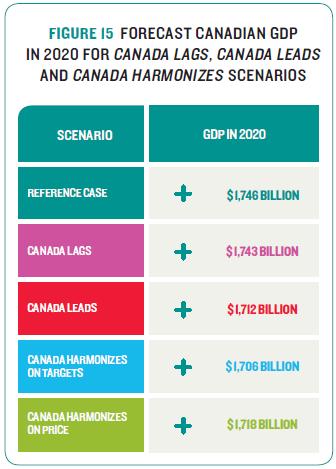

In all cases, the modelling shows that while there is less economic growth with any climate policy compared to no policy, that growth is impacted only modestly. The economy does not shrink; it simply does not grow as much as it is projected to grow otherwise. Figure 15 illustrates the forecast GDP under the four main scenarios.

Yet the results raise a question as to other factors at play. Are there other economic or policy drivers causing economic impacts beyond carbon price differentials between the two countries? Any effective climate policy leads to some costs and hence, to impacts on the economy. So, what are the key drivers of economic impacts for Canada — Canada’s own emission reductions policy or differences between Canadian and American policies?

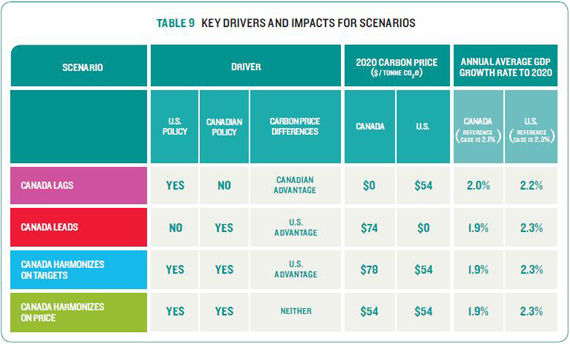

Table 9 sets out the key drivers for each of the four NRTEE policy scenarios: Canada Leads, Canada Lags, Canada Harmonizes on Targets, and Canada Harmonizes on Price. We identify three key drivers: U.S. climate policy, Canadian climate policy, and carbon price differential. For example, when only Canada implements policy, impacts under the scenario result from the Canadian policy driver and from the competitiveness policy driver because there is a carbon price in Canada but not in the U.S. Similarly, when only the U.S. implements policy, Canada would experience decreased demand for exports to the U.S., but would also enjoy a competitive advantage in that Canadian industry would not face added costs for their GHG emissions.

THREE CONCLUSIONS CAN BE DRAWN FROM THIS ANALYSIS :

- CANADA’S OWN POLICY is the largest driver of impacts. Effective Canadian climate policy that drives Canadian emission reductions imposes costs on the Canadian economy as it restructures — costs that are independent of U.S policies and their impacts.

- U.S. POLICY IMPOSES COSTS on the Canadian economy, but these costs are secondary to those imposed by Canadian policy. Effective climate policy implemented in the U.S. causes similar restructuring of its economy over time with additional costs imposed. Any dampening of the U.S. economy subsequently imposes costs on Canada through decreased demand for Canadian goods in the U.S. and reduced exports.

- DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CANADIAN AND U.S. carbon prices can result in competitiveness impacts to Canada, both positive and negative. If policy is more stringent in Canada than in the U.S., American firms could have a competitive advantage over Canadian firms. A significant competitive disadvantage could drive Canadian industry to relocate to jurisdictions with less stringent policy, resulting in negative overall economic impacts for Canada. Yet differences between Canadian and U.S. policy are less important than Canadian policy itself. As Table 9 illustrates, even when carbon prices in Canada and the U.S. are matched in the Harmonized on Price scenario, removing any competitive advantage either country might enjoy as a result of less-stringent policy, costs to Canada still exist as evidenced in the lower GDP growth rate relative to the reference case.

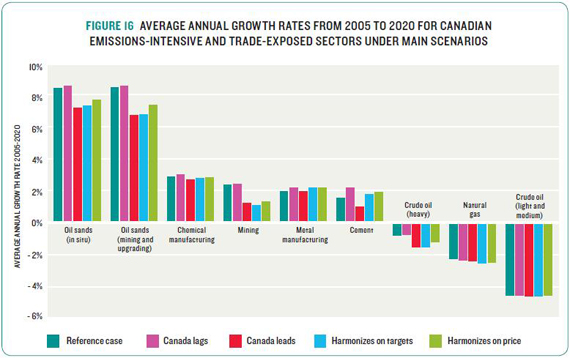

As the NRTEE noted in its Achieving 2050 reports,35 competitiveness is largely a sectoral story. How then are Canada-U.S. climate policy impacts distributed among specific sectors in Canada? Figure 16 illustrates the GDP impacts for emissions-intensive and tradeexposed sectors under our four main scenarios: Canada Leads, Canada Lags, Canada Harmonizes on Price, and Canada Harmonizes on Targets.

TWO KEY FINDINGS EMERGE FROM THIS ANALYSIS :

FIRST, the results confirm that sectors that are emissions-intensive and trade-exposed are most affected by carbon price differentials between Canada and the U.S.36 When Canada lags and the U.S. acts alone, these sectors grow more rapidly, enjoying a competitive advantage over their U.S. competitors. On the other hand, when Canada acts alone, these sectors are disadvantaged. When both the U.S. and Canada implement policy, this impact is significantly mitigated when the carbon prices are the same in the U.S. as shown in the harmonized scenario.

SECOND, the analysis reinforces that Canada has influence over only some of the economic impacts that would be imposed on the Canadian economy by climate policy. Aligning carbon prices with the U.S. will reduce, but not eliminate, negative economic impacts. Some sectors, such as oil sands producers, are affected more by overall stringency of Canadian and U.S. policy, not by the relative difference between policies in each country. However, Canadian policy choices can reduce economic impacts to some extent: if Canada wishes to achieve actual domestic emission reductions, some costs cannot be avoided.

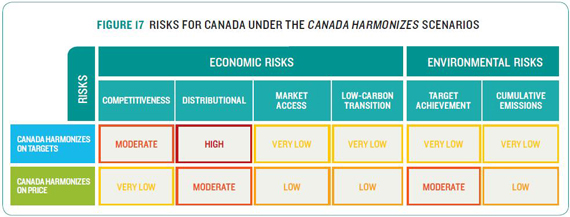

Figure 17 qualitatively summarizes our assessment of economic and environmental risks for Canada of harmonizing with the U.S. If Canada were to harmonize with the U.S. on targets, it would still face competitiveness and distributional risks from higher prices in Canada relative to the U.S. On the other hand, if it were to harmonize on price, it would face risks of not achieving its 2020 targets and setting Canada up for the risk of more challenging and more expensive emission reductions in the long term. Harmonizing on carbon price would moderate but not eliminate market-access risks in the form of U.S. border adjustments, which could potentially be applied based on comparability of targets.

[32] In these scenarios, the U.S implements a cap-and-trade system to achieve its 2020 target of 17% below 2005 levels, with 20% of its compliance coming from international permits. We model U.S. policy as this simplified economy-wide cap-and-trade system so as to have a common point of comparison across the Canada Lags, Canada Leads, and Canada Harmonizes scenarios. Permits to large emitters are allocated for free as output-based allocations in order to reflect trends toward free permits in the U.S. The rest of the economy is covered through an upstream cap with permit auction and revenue recycling 50% to corporate and 50% to income tax. This split reflects a neutral distribution; revenue is roughly distributed back to households and firms in the proportion in which it was collected. In the first scenario, Canada implements comparable policy to achieve the same targets. In the second, the Canadian carbon price is constrained to match the U.S. carbon price, resulting in fewer percent emission reductions in Canada relative to the U.S. relative to 2005 emissions.

[33] Clapp, C., Karousakis, K., Buchner, B., & Chateau J. (2009), and Morris J., Paltsev S., & Reilly J (2008).

[34] All these scenarios represent variations on the case in which Canada and the U.S each implement a cap-and-trade system to achieve 2020 target of 17% below 2005 levels, with 20% of its compliance coming from international permits. We model U.S. policy as this simplified economy-wide cap-and-trade system so as to have a common point of comparison across the Canada Lags, Canada Leads, and Canada Harmonizes scenarios. Permits to large emitters are allocated for free as output-based allocations in order to reflect trends toward free permits in the U.S. The rest of the economy is covered through an upstream cap with permit auction and revenue recycling 50% to corporate and 50% to income tax. This split reflects a neutral distribution; revenue is roughly distributed back to households and firms in the proportion in which it was collected. In the Canada Leads and Canada Lags scenarios, only one country implements this policy by 2020, while the other has no policy at all. In the Canada Harmonizes on Price scenario, the Canadian carbon price is limited so as to match the price of carbon in the U.S.

[35] NRTEE (2009), NRTEE (2009a).

[36] Bramley, M., Partington, P.J., & Sawyer D. (2009), and National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy (2009).