Parallel Paths – 4.2 Aligning Carbon Prices through Cost Containment Measures

Cost containment mechanisms can help align carbon prices between Canada and the United States, addressing competitiveness issues.

Use of these mechanisms could effectively result in a harmonized carbon price between the two countries and has some of the benefits of linkage without implementing a fully linked North American carbon-trading market. Mechanisms under Canadian control include allowing for international and domestic offsets as well as a safety valve to contain the price of carbon.

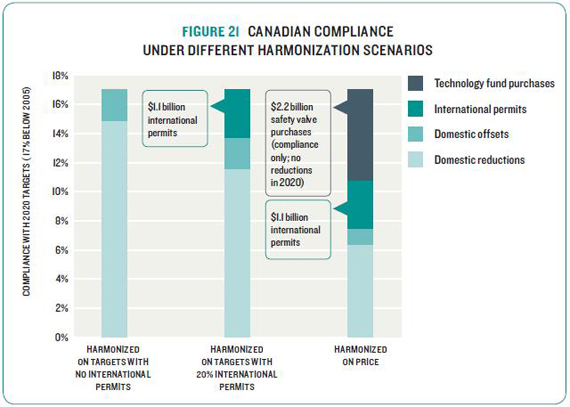

An alignment approach to match Canadian and American carbon prices does, however, pose possible trade-offs for achieving emission-reduction targets. Alignment with a lower U.S. carbon price results in less Canadian abatement, which then leaves a compliance gap that must be filled if environmental goals are to be maintained. Figure 21 highlights this trade-off. It shows how the Canadian economy is expected to meet its 2020 emissions cap under three different policy scenarios. With no international permits, compliance must be achieved through domestic reductions alone, whether emissions abatement or domestic offsets. If some purchases of international permits are allowed, less domestic abatement occurs. And finally, if Canada harmonizes with a U.S. carbon price using a safety valve, even less domestic abatement takes place, with the gap made up through purchases of additional permits from the government via the safety valve mechanism.

As noted, we consider three main design options for price alignment leading to cost containment: a safety valve with a technology fund, access to international permits, and domestic forestry and agriculture offsets. Each is explained below:

TECHNOLOGY FUND

Canada could align carbon prices with the U.S. through a technology fund. Under such a mechanism, the government would sell additional permits to firms at a fixed price. Because these additional permits would be available at the level set by government, permits would not be valued higher than this threshold on the open market. This mechanism, known as a safety valve, limits the market price of carbon and sets a price ceiling. The safety valve becomes a technology fund when the government revenue from sales of additional permits is reinvested in low-carbon technology, providing additional incentives for development of low-carbon technologies beyond a carbon price.

Similar to the other mechanisms discussed in this section, the trade-off here is that containing costs can threaten the achievement of targets since the purchase of permits using a safety valve does not necessarily result in an immediate, realized emission reduction. A technology fund brings other challenges. It could prove to be a barrier for linkage with the U.S. given that it does not ensure that the capped level of reductions is actually achieved. The more firms access the safety valve to comply with their cap, the less domestic emissions are reduced. It would effectively “bust the cap.” As a result, the U.S. might consider this Canadian system non-comparable and justification for border adjustments and for not linking cap-and-trade systems. However, the technology fund could to be structured to meet the criteria in U.S. proposals for ensuring an absolute level of reductions. For example, guarantees could be established that stipulate a fixed number of additional permits issued every year. Alternatively, similar to the Kerry-Lieberman bill, for every permit granted through the technology fund for compliance in the present, government could reduce the total number of allocations to be available in future compliance periods. This approach would ensure that over time, the total number of permits allocated would be limited.50

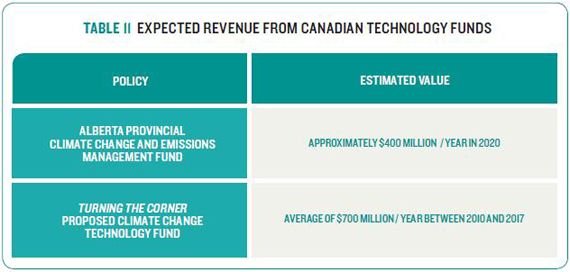

In the long term, revenue from a technology fund could increase the development and deployment of low-carbon technologies, no matter what policy choices the U.S. makes. The risk for Canada is that the limited carbon price under the safety valve could dampen expectations for higher Canadian carbon prices over the long term — and higher prices are needed to develop CCS and other technologies. Table 11 illustrates estimated values of technology fund deposits for the Alberta technology fund (operational) and the original proposed federal technology fund (on hold) for the Turning the Corner plan. It is unlikely that compliance payments into a Canadian technology fund would be sufficiently large on their own to fully finance expensive CCS technology development and deployment. Nevertheless, it could begin to establish a useful source of investment revenue for government and industry for necessary low-carbon technology development and deployment. These investment dollars could provide critical leverage to help induce additional private investment. Further, testing and demonstration of CCS can lead to learning and improvements in technology and decreased costs for broader deployment.51

The Alberta Climate Change and Emissions Management Fund provides some useful learning. In a recent report by the Conference Board of Canada52 on the economic and employment impacts of climate-related technology investments in Canada, the Alberta system is singled out as a model that “appears to be working, based on the revenues generated to date and the fact that emitters are making use of all compliance options. They are reducing emissions, purchasing offsets, and trading in credits, as well as contributing to the technology fund.” The report goes on to note that “the flexibility inherent in this system allows emitters to select the mix of options that best suits their circumstances.” While the report does qualify that it is still too early in the investment cycle to quantify the emissions impact of the Fund, it is expected to generate and implement emissions reducing technologies that will “contribute to reaching targets and provide sales opportunities on international markets.” In June 2010, for example, Alberta’s fund handed out $5.7 million for six energy efficiency projects.53.

ACCESS TO INTERNATIONAL PERMITS

Allowing Canadian firms to comply with some of their emission-reduction obligations (the “cap”) through the purchase of international permits would allow them to avoid higher cost emission reductions domestically. Increased access to international permits54 would also lower the Canadian carbon price, pulling it closer to the U.S. price. This mechanism is important to consider as the U.S. proposals from the House and Senate all include extensive opportunities for compliance through international permits.55 Canadian firms would be at a competitive disadvantage if similar measures were not reflected in Canada’s climate policy. However, international permits could pose potential problems due to concern regarding challenges in verifying the credibility of international permits, unanticipated social and environmental implications, and flows of investment out of Canada.

Allowing real, verifiable, and measurable international permits would not affect the environmental effectiveness of the policy as emission reductions have the same effect in reducing climate change independent of their geographic location. However, this point is predicated on the assumption that the international reductions achieved are verifiable and additional. That is, sufficient quality control would be required to ensure that every reduction would not have occurred in the absence of the purchase of the permit. It also would be necessary to ensure that permit projects are environmentally and socially sustainable to ensure the integrity of the policy.56

Aligning prices through international permits poses some of the same economic risks that linkage does in that it implies comparable financial transfers out of Canada. NRTEE modelling suggests that this could amount to around $3 billion in 2020.57 Flows of investment outside Canada could also have implications for long-term low-carbon competitiveness in Canada. Money spent on international permit purchases to reduce short-term costs of GHG obligations is money not spent on the long-term low-carbon technology innovation, development and deployment necessary to succeed in a global low-carbon economy. Further, it is important to note that availability of low-cost international reductions from developing countries58 could be limited or delayed given lack of institutional capacity and competition from other countries with domestic cap-and-trade systems. In this case, the price of international emission reductions would be higher and less desirable. U.S. policy proposals like Waxman-Markey and Kerry-Lieberman rely extensively on international offsets, and analyses of these policies by the EPA largely assume international supply will be sufficient to meet this demand.59 Yet the EPA analysis also recognizes uncertainty in the supply of these offsets due to limited institutional structure in developing countries to ensure that offsets are credible and meet quality standards.

The NRTEE’s analysis follows similar thinking presented in the EPA analysis. Two elements of our analysis explicitly explored the issue of international permit availability. First, our assumption in the price of international offsets was dependent on U.S. policy in each scenario. This assumption explicitly recognized that there would be competing demand for international offsets, and that the U.S. would likely be a major buyer of permits if it implemented policy.60 Second, like the EPA, we also explored scenarios in which no international offsets were allowed. In these scenarios, the price of carbon and costs of Canadian policy were correspondingly higher.

DOMESTIC OFFSETS

Access to domestic offsets is another mechanism for containing costs for Canadian firms. The extent to which offsets can be used to lower the Canadian carbon price (and thus to align with the U.S.) depends on the availability of real, verifiable, and measurable emission reductions from offsets in Canada. The NRTEE modelling considers only landfill gas. However, domestic forestry and agricultural offsets could contribute toward emission reductions in Canada. Domestic offsets from these and other industries could also reduce the required carbon price in Canada; however, a full analysis of these additional non-energy offsets is outside the scope of this analysis. Alternatively, as suggested in Achieving 2050, complementary regulations could be applied where possible to ensure emission reductions from non-energy emission sources not easily included in a cap-and-trade system.

U.S. analyses61 suggest that extensive low-cost reductions may be available from U.S. forestry offsets. Canada may need to explore its own potentially large opportunities for land-use offsets. Little research has been conducted to date on changes in Canadian forestry practices to deliver credible, additional emission reductions and the costs at which they might be achieved, although U.S. studies give some sense of potential.62

[50] This approach also parallels the U.S. stability reserve in the American Clean Energy and Security Act. For every additional compliance permit issued by the government under the safety valve, future (post-2020) caps could be tightened. Effectively, the safety valve would provide a mechanism for borrowing from future compliance periods. A significant challenge for this option is the need to develop institutional capacity to ensure this borrowing is credible: would future governments adhere to the tighter targets in the long term? More analysis of this option is required. Yet given that the technology fund would provide support for technologies to enable longer-term emission reductions, requiring more stringent reductions in the long term may be feasible. Further, this approach could even potentially allow for eventual linkage with the U.S. because it would ensure absolute reductions, at least over the longer term.

[51] Natural Resources Canada (2008).

[52] Conference Board of Canada (2010).

[53] Edmonton Journal (2010, June 23).

[54] International permits are emission reductions in other countries, and are bought and sold internationally. They could be permits from a other trading system such as the European ETS, but are more likely to be lower-cost reductions from the developing world from sources such as avoided deforestation. They could be obtained through existing mechanisms such as the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) or the international institution that is established as the successor to CDM. Finally, even permits from a U.S. trading system could be accepted. Accepting U.S. permits would be a one-way linkage; U.S. permits would be accepted in Canada (if non-U.S. firms are allowed to participate in a U.S. carbon market) without Canadian permits necessarily being accepted in the U.S.

[55] While we did not model a scenario with unlimited international permits in Canada and the U.S., such an approach could potentially harmonize Canadian and U.S. carbon prices through an effect known as indirect linkage. See Jaffe, J., & Stavins, R. (2007). If both Canada and the U.S. draw on the same pool of international permits, the carbon price in both countries will be drawn in the direction of the international market price. Both countries will avoid reductions that are more expensive than international permits. This indirect linkage can result some in convergence of carbon prices even without direct trading between the two countries.

[56] Environmental and community groups have criticized the World Bank-managed Prototype Carbon Fund for funding large-scale development projects such as a eucalyptus plantation in Brazil, a hydroelectric dam in Guatemala, and a landfill in South Africa. These groups have argued that such projects may cause social and environmental harm. Ensuring the quality, equity, and sustainability of international permits can thus be a challenge and may pose some risks for the environmental effectiveness of the policy as a whole.

[57] The cost of aligning prices with the U.S. through international permit purchases depends on the stringency of U.S. policy and on the cost of international permits. The $3 billion estimate assumes Canadian and U.S. carbon prices of $54/ tonne, with sufficient international permits (purchased at $50 / tonne) to make up the remainder of Canada’s target. Keeping Canada’s carbon price even lower would require more international permit purchases.

[58] Studies have estimated that large shares of low-cost offsets would likely come from reductions in deforestation in developing nations, which could require institutions to ensure reductions are verifiable and permanent and do not have other adverse social or economic impacts. See Commission on Climate and Tropical Forests (2009) and McKinsey and Company (2009).

[59] The EPA’s core scenario in its analysis of Kerry-Lieberman assumes U.S. firms will purchase between 600 to 1000 Mt of international offsets per year. See U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Atmospheric Programs (2010).

[60] We assumed a fixed price for international reductions of $25 / tCO2e if the U.S. implements policy and a fixed price of $50 / tCO2e if the U.S. does not. The analysis therefore does not incorporate a detailed supply curve for international reductions. However, given the uncertainty the price and availability of international reductions, these conservative benchmarks provide useful representation of possible international reductions.

[61] Congressional Budget Office (August, 2009), and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Atmospheric Programs (2009) and (2010).

[62] This area seems to be a research gap in Canada. However, for analysis on Canada’s forests and forests industry and GHG emission reductions, see U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Atmospheric Programs (2005); U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2010); Boyland, M. (2006); McKenney, D. W., Yemshanov, D., Fox, G., & Ramlal, E. (2004); Yemshanov, D., McKenney, D. W., Hatton, T., & Fox, G. (2005); Graham, P. (2003); Natural Resources Canada (2009).