Parallel Paths – 3.0 Assessing Risks in Canada-U.S. Climate Policy

The biggest risks for Canadian climate policy stem from U.S. climate policy uncertainty. This uncertainty complicates our own policy choices in response.

A range of legislative proposals were considered in the U.S. in 2010, including the economy -wide cap-and-trade system in the House of Representatives’ Waxman-Markey bill, and the parallel Kerry-Lieberman Senate bill that proposed starting with electricity generation and transportation and phasing in large manufacturing.18 Given that no legislation was passed, an EPA-led regulatory approach also remains a possibility.

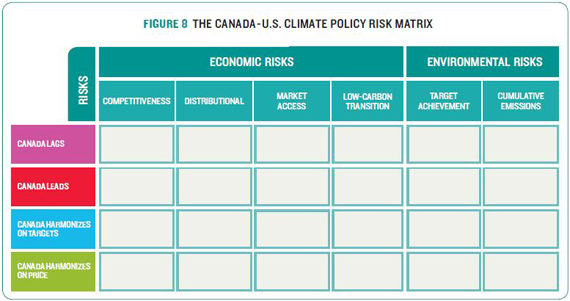

Canada has three choices in the face of this uncertainty. It can wait until the U.S. implements some form of climate policy, it can take immediate action ahead of the U.S., or it can harmonize its policy with what is being considered in the U.S. This chapter details an assessment of both the economic and environmental risks associated with each of these three choices for Canada through three illustrative scenarios :

- CANADA LAGS THE U.S. on climate policy. In this scenario, the U.S. implements policy ahead of Canada. If Canadian policy lags, this means higher costs imposed on the U.S. economy but not on Canada’s. While there are competitiveness benefits for some Canadian firms, there is a key risk of U.S. trade measures being applied to Canadian exports (in the form of border carbon adjustments) as well as the environmental risk of not achieving Canada’s GHG targets.

- CANADA LEADS THE U.S. on climate policy. In this scenario, Canada implements policy ahead of the U.S. The key risk is to our economy, with likely competitiveness impacts on emissions-intensive, trade-exposed firms and specific regional economic impacts. This scenario reduces the environmental risks of not achieving emission reduction targets.

- CANADA HARMONIZES WITH THE U.S. on climate policy. In this scenario, Canada and the U.S. both implement policy along the same lines. At present, harmonization is occurring on targets and on some regulatory measures (vehicle emission standards). But harmonization on GHG targets is different than harmonization on carbon price and so these are assessed separately as there are economic and environmental risks to Canada of one approach over the other.

Throughout this chapter, we will assess the key economic and environmental risks to Canada for each of the three scenarios. By assessing these risks, we are then able to identify and explore possible opportunities to address these risks in the following chapter.

ECONOMIC RISKS

- COMPETITIVENESS RISKS stem from differential carbon prices between Canada and the U.S. They impact a small but important subset of our national economy that is emissions-intensive and trade-exposed.

- DISTRIBUTIONAL RISKS arise from Canadian climate policy choices. While regional and sectoral economic-impact risks are somewhat affected by relative carbon prices in Canada and the U.S., they are more strongly affected by the chosen elements of Canadian policy than whether or not the U.S. implements policy.

- MARKET ACCESS RISKS are associated with U.S. trade measures such as border carbon adjustments or a low-carbon fuel standard. These measures could pose a direct risk to Canadian exports to the U.S. by imposing additional costs on and/or limiting demand for our energy exports.

- LONG-TERM LOW-CARBON-ECONOMY TRANSITION RISKS occur when climate policy fails to drive technological change and innovation. Reducing emissions in the Canadian economy will become more expensive to accomplish and more difficult to achieve. Further, Canadian industry will be less well positioned to compete in large emerging global markets for low-carbon technologies and services.

ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS

- THERE IS A TARGET ACHIEVEMENT RISK with Canada not realizing its stated 2020 emission reductions target. This risk is largely a function of Canadian policy choices since more stringent domestic policy results in more GHG reductions, but if U.S. uncertainty leads to Canadian delay, then this outcome is inevitable.

- THERE IS A CUMULATIVE EMISSION RISK. That is, the longer significant action to reduce emissions is delayed, a greater amount of emissions contributed by Canada accumulates in the atmosphere and remains there for a longer period of time.

To assist in this analysis, we have created a Canada-U.S. Climate Policy Risk Matrix to illustrate which risks arise from each scenario. In order to present as comprehensive an illustration of risks as possible, we have taken a two-step approach — first, we analyzed the magnitude of the impacts of each risk and second, we analyzed the likelihood of the risk within each scenario.19 The risk matrices in this chapter show the combined results of both steps. Each source of risk is assessed as very low, low, moderate, or high to give a full range of possibilities that could ensue. Although no scenario is entirely risk-free, our quantitative and qualitative analysis allows us to characterize these risks and to identify policy choices for Canada that offer the narrowest range of risks or those that could be the most manageable. Figure 8 illustrates this framework. We populate the framework by assessing risks through the remainder of this chapter.

[18] Other bills that have been discussed in the U.S. include the initial Senate bill, Kerry-Boxer (S. 1733), which closely resembled the Waxman- Markey bill (H.R. 2454), and the Cantwell-Collins bill (S. 2877), a simplified upstream approach that imposed a cap on upstream fuel distributers.

[19] See Appendix 7.2 for the full breakdown of this analysis.