Parallel Paths – 3.1 Canada Lags the U.S. on Climate Policy

This section explores the implications for Canada from both environmental and economic perspectives of lagging behind the U.S. on implementing climate policy.

It assesses impacts on the Canadian economy of U.S. policy from the perspective of competitive advantage, decreased growth in the U.S., and border carbon adjustments.

ENVIRONMENTAL RISKS

With no Canadian climate policy, Canadian emissions continue to grow to about 10 % above 2005 levels in 2020, significantly higher than Canada’s target of 17 % below 2005 levels. As we have shown, existing policies at this stage are insufficient to achieve Canada’s current emission-reduction targets.20

A further environmental risk emerges for long-term reductions. If Canada lags on climate policy, firms have no expectations of the long-term value of carbon and will fail to invest in necessary low-carbon technology choices or innovation. While less-stringent Canadian policy reduces economic impacts in the short term, it stimulates less innovation and commercialization of new low-carbon technologies, essential both for achieving long-term targets as well as for being competitive in a future carbon-constrained global market. Achieving the deeper longer-term emission reductions required to meet targets becomes more difficult because they become more expensive. Not addressing Canadian emissions thus creates the obvious but real environmental risks of missing targets and of increased cumulative GHG emissions as a result.

ECONOMIC RISKS

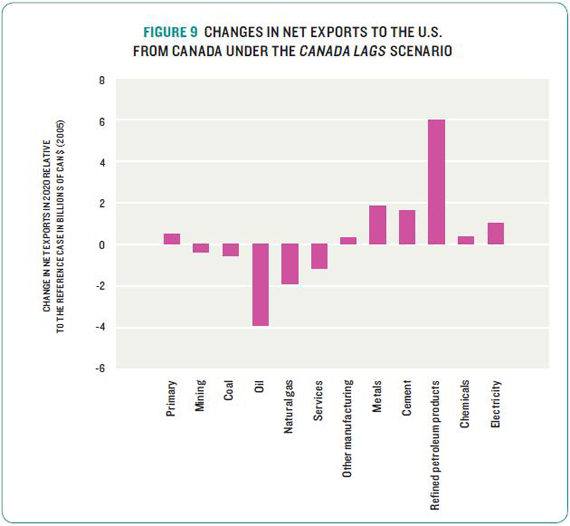

With U.S. climate policy only (and presuming no countervailing border measures), the NRTEE modelling suggests that Canada’s overall trade surplus would likely increase as Canadian goods become less expensive to U.S. buyers. U.S. climate policies would necessarily increase energy costs and subsequently the price of U.S. goods, and in the absence of comparable policies in other countries, could disadvantage domestic producers in U.S. markets. Our modelling results, as illustrated in Figure 9, show that Canadian exports of metal, cement, chemicals, and refined petroleum products would increase as a result of this advantage. Yet this gain is partly offset by dampened demand in the U.S. for emissions -intensive exports. Our analysis suggests that a U.S. climate policy would trigger a decline in demand as the American economy contracts in response. Exports of some products — such as oil and gas, coal, and mining products — fall in the Canada Lags scenario forecast, which then lowers Canada’s national income in 2020 by about 0.2 % of GDP. Table 5 shows these national results.

BORDER CARBON ADJUSTMENTS (BCAs)

BORDER CARBON ADJUSTMENTS (BCAS) are an approach to addressing competitiveness issues through requiring imported goods from jurisdictions without a carbon pricing policy to pay for their un-priced carbon emissions costs, and / or relieving exports of their expected emissions costs. Their aim is to “level the playing field” for firms either in domestic or international markets. Our analysis focuses primarily on U.S. import tariffs, represented in the Waxman-Markey bill as International Allowance Reserves, a form of BCAs.

To protect against sectors in other countries having a competitive advantage over comparable U.S. sectors under climate policy, the U.S. could very likely implement trade measures, like Border Carbon Adjustments (BCAs), as part of its climate policy. Canada’s extensive trade with the U.S. could be vulnerable to these measures on two counts: if we lagged behind the U.S. on climate policy or if our own policy were less stringent than U.S. policy.

Though the specific nature of border measures are uncertain, emerging U.S. climate policy proposals, including the American Clean Energy and Security Act (Waxman-Markey bill), the Clean Energy Jobs and American Power Act (Kerry-Boxer bill), and the American Power Act (Kerry-Lieberman bill) provide a useful lens through which to view trade risks for Canada. All three proposals contain provisions to impose costs on certain imported products from countries with comparable carbon policies. If Canadian policy was not deemed comparable, such trade measures would impose additional costs on Canadian exports. Canadian firms from sectors identified as vulnerable in the U.S. bills21 would be subject to BCAs if they are not subject to climate policy comparable to their counterparts in the U.S.

Each of the bills includes provisions for BCAs in the form of an Import Allowance Reserve (IAR).22 This mechanism would require importers of goods from those same designated manufacturing sectors to purchase U.S. emissions allowances to offset the carbon footprints of their products.23 However, BCAs would only be implemented if the first line of defence for vulnerable industry — free permit allocations for emissions-intensive and trade-exposed sectors, designed to act like a subsidy for these sectors — were deemed insufficient. This constraint on U.S. importers is meant to correct any remaining carbon-cost discrepancy relative to industry in jurisdictions without comparable policy.

Exemption from border measures is offered to countries party to a multilateral climate agreement along with the U.S. with policies of comparable stringency — or if the imported goods are less carbon intensive than their U.S. counterparts, which may be achieved with less stringent policy. Under the Kerry-Lieberman bill, border carbon adjustments could only be applied after 2020 if no international climate agreement is in place. U.S. policy has been designed with emerging economies, such as China and India, more in mind than Canada, but the popularity of border measures among key U.S. constituencies leads to uncertainty and risk for Canada in how the provisions will be incorporated and ultimately applied.

To assess the full range of Canadian exposure to American BCAs and what its maximum impact could be, we considered the implications of a border carbon adjustment on all Canadian exports, not just those from sectors identified by the U.S. bills as vulnerable to competitiveness risks. The results, therefore, likely overstate impacts. The adjustment was made based on the carbon intensity of Canadian exports. The BCA level was illustrated as the U.S. carbon price applied to a specific industry.

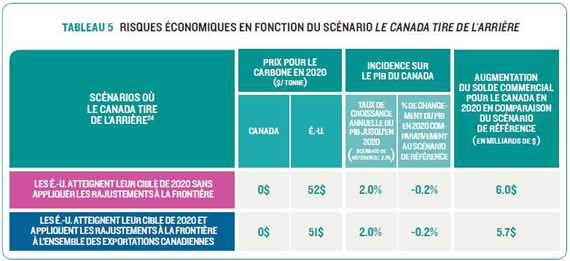

The results are presented in Table 5. Economic growth is positive, but slightly less than it would have been in the absence of the policy as a result of dampened U.S. demand. Not surprisingly, Canadian exports are negatively affected if the U.S. applies border carbon adjustments equivalent to the U.S. carbon price. Canada’s trade surplus with the U.S. is reduced by approximately $300 million in 2020, although not eliminated, if the U.S. implements BCAs. The border adjustment decreases the gains Canada would experience under the main Canada Lags scenario. Overall, Canada’s trade surplus with the U.S. still increases relative to the reference case, even with the BCAs.

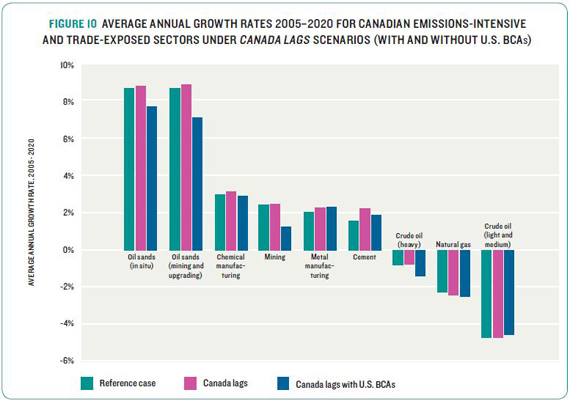

Some Canadian sectors are affected by the BCAs more than others. Figure 10 illustrates the sectoral impacts of American BCAs on the Canadian trade-exposed and emissionsintensive sectors. Oil and mining sectors show the biggest impacts under this scenario.25 Figure 10 shows that the impacts of a U.S. BCA are not uniform at a sector level; while the national economic growth rates are not appreciably affected by the BCA, some sectors show clear reductions in growth.

A LOW CARBON FUEL STANDARD (LCFS)

A LOW CARBON FUEL STANDARD (LCFS) is a regulation that mandates a decreasing carbon content in the total pool of transportation fuels.

Low carbon fuel standards (LCFS) pose a similar risk as BCAs but for different reasons. LCFS requires that the carbon content of transportation fuels meet a minimum standard. The intent of LCFS is to reduce dependence on imported oil and reduce carbon emissions. A LCFS is designed to encourage biofuels in the transportation sector, but will also likely be a disincentive for fuel refined from more carbon-intensive sources such as the oil sands. The economic risk for Canada is a reduction of export revenue from oil, and from oil produced from oil sands in particular, given its relatively high carbon content as compared to conventional oil. While there is currently no national LCFS in the U.S., it has been discussed, and some states are proceeding in this direction, with California implementing a LCFS.

A recent report from Ceres, a U.S. think tank,26 finds that more than half of the U.S. states and four Canadian provinces are weighing the adoption of LCFS to reduce the carbon intensity of some petroleum fuels. In particular, the report identifies emerging low-carbon fuel standards in the U.S. as jeopardizing Canadian fuel from oil sands production to longterm access to the U.S. market.27 California’s LCFS requires a 10 % reduction in the average carbon intensity of motor vehicle fuels by 2020. States in the northeast may soon follow suit. Together, these states comprise one-quarter of U.S. demand for transportation fuels. Adoption of LCFS would place oil sands producers at a disadvantage to conventional petroleum producers, because their synthetic crude oil is around 12 % more carbon intensive than average crude oil. That means oil sands suppliers would need to achieve a 20 % total reduction in carbon intensity over the next decade in order to meet the average regain under an LCFS based on the California standard.

The Ceres report concludes that the adoption of an LCFS would have a negative impact on projected oil sands production under any scenario considered. For example, it suggests that a U.S. federal standard seeking a 20 % reduction in the carbon intensity of transportation fuels could result in a 33 % reduction in oil sands production relative to projected growth. The analysis does not consider how alternative markets for oil-sand products (potentially enabled through a future pipeline to the Pacific) could mitigate these impacts.

Finally, lagging behind the U.S. in climate policies will hinder the development and deployment of new low-carbon technologies. As other nations around the world implement climate policies, new markets will emerge for low-carbon goods and services. Canada will be less well-positioned to compete in these markets and to seize these new opportunities without domestic climate policy, including a carbon pricing policy. 28

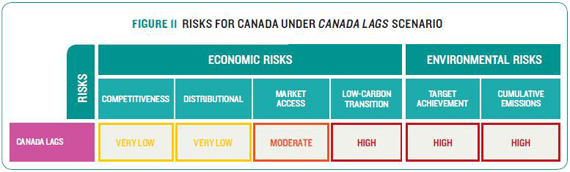

Figure 11 qualitatively summarizes our combined assessment of the economic and environmental risks if Canada were to lag behind the U.S. on climate policy. Certain Canadian industries would experience competitive advantage relative to the U.S., though economic risks from U.S. trade measures would partially offset these gains. Therefore, while competitiveness and distributional risks are very low, market access risks are moderate. Canada would also face long-term economic risks from higher costs of reducing emissions given delays in Canadian policy. Lagging would also delay Canada’s transition to a low-carbon economy and development of innovative low-carbon technologies. Similarly, it faces clear environmental risks in terms of achieving both short- and long-term reductions. Therefore, the risks of not achieving targets and greater cumulative emissions for Canada are high.

[20] See Figure 6 on page 39, which illustrates the estimated reductions from Environment Canada from announced government policies.

[21] As discussed in Chapter 2, the Waxman-Markey bill identifies those U.S. sectors with potential competitiveness risks deemed to be emissions-intensive and trade-exposed (EITE). Oil and refined petroleum products are excluded under the EITE designation.

[22] The IAR is defined in the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009, H.R. 2454, section 768.

[23] The Kerry-Boxer bill (S.1733) does not contain specific detail for an IAR, however a place-holder in Section 765 states that, ‘‘It is the sense of the Senate that this Act will contain a trade title that will include a border measure that is consistent with our international obligations and designed to work in conjunction with provisions that allocate allowances to energy-intensive and trade-exposed industries.’’ See the Clean Energy Jobs and American Power Act of 2009, S. 1733, section 765.

[24] In these scenarios, Canada implements no policy. The U.S. implements a cap-and-trade system to achieve its 2020 target of 17% below 2005 levels, with 20% of its compliance coming from international permits. We model U.S. policy as this simplified economy-wide cap-and-trade system so as to have a common point of comparison across the Canada Lags, Canada Leads, and Canada Harmonizes scenarios. Permits to large emitters are allocated for free as output-based allocations in order to reflect trends toward free permits in the U.S. The rest of the economy is covered through an upstream cap with permit auction and revenue recycling 50% to corporate and 50% to income tax. This split reflects a neutral distribution; revenue is roughly distributed back to households and firms in the proportion in which it was collected. Note that this scenario is illustrative, and is not an exact replication of the Waxman-Markey bill, or any other specific proposed legislation. It does not include the same level of offsets proposed in the Waxman-Markey bill, and so has a higher carbon price. In the second scenario, the border carbon adjustment (BCA) imposes the same carbon price on all Canadian exports to the U.S. Again, this BCA scenario is more severe than the more limited one proposed in Waxman-Markey. It is intended to better represent the worst-case scenario.

[25] Again, note that under the Waxman-Markey bill, oil is not an eligible sector under the BCAs, though it is included here to represent the worst-case scenario.

[26] RiskMetrics Group (2010). Report commissioned by Ceres.

[27] More than half of U.S. states and four Canadian provinces are weighing adoption of LCFS to reduce the carbon intensity of some petroleum fuels.

[28] The NRTEE has begun to explore this issue in the recent report Measuring Up: Benchmarking Canada’s Competitiveness in a Low-carbon World. (NRTEE, 2010). It will explore this issue in even more detail in the sixth report of the Climate Prosperity series.