4.1 International Competitiveness – Life Cycle Approaches

Canada is an exporting nation with internationally and regionally integrated supply chains. The increasing inclusion of Life Cycle Approaches in private sector supply-chain requirements and foreign public regulations has exposed the country to economic risks to international competitiveness. Both the private and public sectors need to step up their use of Life Cycle Approaches to remain competitive in this new reality.

TRADE RESTRICTIONS

Several international regulations threaten to restrict Canadian companies’ access to international markets through the required disclosure of life cycle impacts for products and commodities. This is of particular significance as the Canadian economy relies heavily on exports. In 2010, exports of goods and services accounted for 29% of Canada’s GDP,91 with a total of approximately $400 billion worth of goods sold to other countries.92 The U.S. is Canada’s largest trading partner by far, accounting for about 70% of exports as of 2010. Canadian exports to the U.S. increased by nearly 9% in 2010 to $333.6 billion. Fewer exports are sent to the EU, however, it still remains an important trading partner. In 2010, $49.2 billion worth of goods and services were exported to the EU, up just over 10% from the previous year.93 A large proportion of Canadian exporters are SMEs. Small businesses comprised approximately 86% of exporters in 2009, for a total value of $68 billion worth of exported goods.

For the same time period, approximately $51 billion worth of exported goods originated from mediumsized businesses.94

So far, two types of government regulations have emerged that use life cycle information. In some cases, businesses are required to disclose life cycle data in order to sell products in certain jurisdictions, as is the case with France’s proposed EPD program (described in Chapter 3) and the EU’s Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) legislation described below. The U.S. EPA’s Environmentally Preferable Purchasing (EPP) Program (detailed in Chapter 3) promotes the use of life cycle information to select the most efficient option that meets the government’s needs.

Launched in 2007 and phased in over an 11-year period, the EU’s REACH legislation will require manufacturers and importers to collate information on chemical substances contained in their products or used during the manufacture of the products, and register these in a database. For substances that are manufactured or imported in quantities over 10 tonnes, companies will also need to provide information on how related risks will be managed during the manufacturing or use phase of their life cycle.95

In other cases, foreign governments are imposing requirements on the content of goods sold in their jurisdiction based on Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) data, such as setting minimum amounts of renewable fuel content in transportation fuels. Renewable fuel mandates and low carbon fuel standards have been used by government bodies interested in reducing GHG emissions from the consumption of transportation fuels in their jurisdiction. Adopted in the U.S., EU and British Columbia, these regulations require the use of LCA to measure and compare the GHG intensity of alternative fuels with baseline fuels from “well-to-wheels.” ††† This type of Life Cycle Approach focuses only on one impact category, GHG emissions, and thus negates the ability to identify effects on other environmental attributes (e.g., water, land use, etc). Nevertheless, these regulations have raised trade issues, market access issues and methodological challenges related to LCA, the impacts of which are already being felt in Canada.

Better life cycle data is needed to allow the comparison of transportation fuels and thus enable fuel choices to be made based on scientific fact.96

Two examples of these types of regulations exist in the U.S. They are the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS2) and California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS). These regulations are described in more detail in the text box below.

Similar types of regulations also exist in the EU, such as the Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and the Fuel Quality Directive. In April 2009, the EU adopted the RED, which requires that at least 20% of its energy mix come from renewable energy sources by 2020.102 This regulation may create similar complications for Canadian renewable fuel and feedstock producers interested in accessing the EU biofuels market. The main risks and uncertainties include the stringency of environmental and social criteria that will be used to evaluate life cycle biofuel performance, modelling of Canadian biofuel pathways using European data and practices, and the impact of biofuel certification costs on agricultural and biofuel producers.

The EU’s Fuel Quality Directive (98/70) mandate was amended in December 2008 to require a 10% reduction in life cycle (well-to-wheel) emissions from transport fuels by 2020.103 The final values for various types of fuels have not yet been approved by national governments, but the proposal approved by the European Commission in October 2011 was to assign default values to oil sands product at 107 g CO2e/MJ, in contrast to conventional fuel at 87.5 g CO2e/MJ.104 Canada has minimal exports of oil to the EU, but the sector sees danger in yet another precedent.

In general, renewable fuel mandates and LCFS have catalyzed a huge change in the energy sector. Previously, the use of Life Cycle Approaches were not necessarily on industry’s radar, but the implementation of these regulations has brought a number of large companies on board—largely because of potentially significant impacts on their businesses.105

Canada needs to keep pace with other countries by creating policies that incorporate Life Cycle Approaches, especially those related to standards and regulations. Other jurisdictions are setting their own criteria that are not harmonized with those in Canada or that are based on analysis or methodologies that result in a competitive disadvantage for Canada. This is important to note as Canada is currently entering into talks with other countries or groups of countries, including India and the EU, to enhance our trading relationships.

Companies that have not adopted Life Cycle Approaches are not prepared for or able to comply easily or quickly with existing or anticipated foreign government regulations that require information based on Life Cycle Approaches. This restricts both the end-use product manufacturers’ and extractive industries’ ability to sell commodities and consumer products in jurisdictions that have requirements and standards based on Life Cycle Approaches. The risk that Canadian companies are not prepared for existing and future foreign government regulations that require Life Cycle Approaches has significant economic repercussions. Businesses can lose part or all of their access to export markets,106 face fines or penalties for not complying with the regulations, or suffer damage to brand recognition. Companies that are forced to comply with the regulations and adopt Life Cycle Approaches in a short time frame face larger and more-immediate investments to build the capacity to respond to this demand or risk losing market share.

The design and implementation of regulations based on Life Cycle Approaches, including the measurement frameworks and indicators used to assess environmental life cycle impacts, have significant implications. For example, environmental indicators should be relevant for the productproduction system being studied and reflective of the local geographic characteristics. Issues or indicators of importance to one jurisdiction may not be of significance to the trading partner.107 If the federal government is not broadly engaged and well informed about the design and implementation of international regulations based on Life Cycle Approaches, there is the risk that the regulations will have negative repercussions for Canada, both economically and environmentally.

By applying or strengthening the application of Life Cycle Approaches in international trade agreement negotiations, the government has an opportunity to influence the development of international agreements based on sound analysis that advance both environmental and economic objectives. Life Cycle Approaches could be used to better understand the environmental impacts of trade agreements on an issue (e.g., land, water, GHG emissions, mercury) or sectoral basis through the stages of resource extraction, production, distribution, use, and disposal/ recycling, as well as their geographic distribution within the trade zone. However, the complexity of trade flows and associated material flows suggests that Life Cycle Approaches would need to be applied in concert with other tools.

The increasing inclusion of Life Cycle Approaches in private sector supply-chain requirements and foreign public regulations has exposed the country to economic risks to international competitiveness.

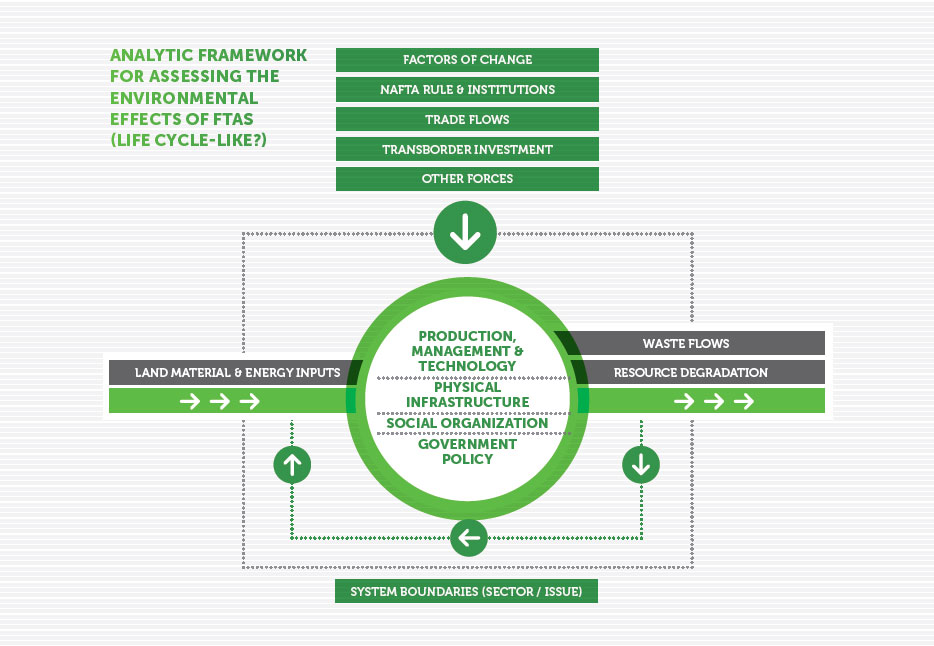

Preliminary work on the application of Life Cycle Approaches to trade negotiations has been performed by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC).§§§ It has conducted extensive analysis of environmental impacts in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) zone, including some analysis based on life cycle and material flow approaches, as illustrated in the CEC schematic reproduced in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6. LIFE CYCLE THINKING IN ASSESSING ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS OF FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS

Source: Adapted from Rodriguez 2007

This analysis has been framed in a manner similar to that used in Life Cycle Approaches. Both the environmental inputs such as land, material and energy, and environmental impacts including waste flows and resource degradation are considered. By comparing resources used at all stages of the life cycle, the effects of trade can be assessed.108 These include NAFTA rules and institutions, trade flows, transborder investments and other forces. While this analysis is not being conducted at the negotiation stage, it demonstrates the use of Life Cycle Approaches in a trade policy context.

LACK OF MARKET ACCESS

Emerging private sector “regulations,” in which business customers are demanding life cycle data and information from suppliers, are affecting many companies across a variety of supply chains. Companies that are not able to satisfy the growing demand for life cycle information will be increasingly disadvantaged. Many sectors, including building and construction, electronics, transport, aerospace, retail, packaging, food and beverage, are facing these business-to-business requirements.

Companies that fail to respond to this demand are likely to experience a decrease in revenue resulting from a loss of market share, the missed opportunity for first-mover advantages, and increased costs reacting to anticipated future customer demands. Revenue can also be lost by missing out on marketing opportunities such as distinguishing products marketed to consumers based on life cycle information of their raw materials or products109 and gaining brand recognition. These losses may increase if the anticipated future demand for this information from individuals and governments is realized.

Companies that do not have the life cycle information of their material inputs or products encounter associated environmental repercussions. These include reduced information for manufacturers on the environmental impacts of their products, resulting in a lost opportunity to reduce impacts on the environment (e.g., air, water, waste) at multiple points of the life cycle.

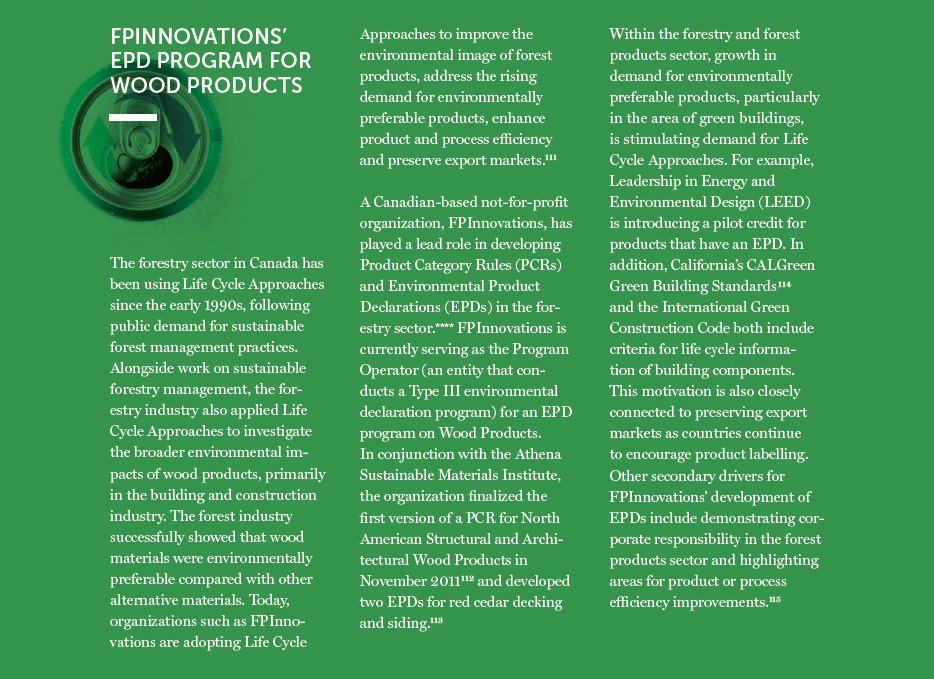

Evidence already exists that companies along the supply chain are starting to ask for information based on the life cycle of products. Walmart’s work with the Sustainability Consortium (see Chapter 3 for more details), and the green building and manufacturing codes and standards (see FPInnovations case study below) are a few examples of these emerging requirements. The most common data of interest is cradle-to-gate (i.e., from resource extraction to factory gate) data on the life cycle performance of materials. For example, within the green building and construction sector there is increasing demand for life cycle data and information on environmental inputs and impacts of basic materials such as concrete, wood and steel.110 In the mining sector, end users, smelters, and mines are starting to track where metals come from and how they are used in products.

[†††] A broad life cycle assessment measurement approach that includes GHGs produced in the course of land use change, resource extraction, feedstock and fuel production, refining, blending, transportation and storage, as well as final use.

[‡‡‡] The standard became effective in January 2010; however, the U.S. federal court issued an injunction against the LCFS in December 2011. California is currently appealing this decision. In the meantime, the legislation is not being enforced (California Environmental Protection Agency Air Resources Board 2011a).

[§§§] The CEC was established as a result of the North American Free Trade Agreement. It monitors and reports on the state of the North American environment in the context of NAFTA.

[****] PCRs establish the requirements of a Life Cycle Assessment specific to a particular product group and are the basis for the development of an EPD. EPDs are a globally recognized third-party verified product declaration based on the ISO 14025 standard. These declarations provide quantified environmental information on the environmental impacts for all stages of a product’s life cycle to help businesses and consumers compare the impacts of similar products.

[91] The World Bank 2012

[92] Industry Canada 2011b

[93] Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada 2011

[94] Industry Canada 2011c

[95] Environment Directorate General 2007

[96] Canadian Petroleum Products Institute 2012

[97] United States Environmental Protection Agency 2011

[98] California Office of the Governor 2007

[99] Mui et al. 2010

[100] California Environmental Protection Agency Air Resources Board ND

[101] California Environmental Protection Agency Air Resources Board 2011b

[102] Foreign Agricultural Service U.S. Mission to the European Union 2010

[103] European Commission Environment 2012

[104] EurActiv 2011

[105] ICF Marbek 2011

[106] Schenck 2009

[107] Demeter Environmental Inc. 2011

[108] Interuniversity Research Centre for the Life Cycle of Products Processes and Services 2007

[109] Schenck 2009

[110] Demeter Environmental Inc. 2011

[111] ICF Marbek 2011

[112] FPInnovations 2011

[113] ICF Marbek 2011

[114] California Buildings Standards Commission 2010

[115] ICF Marbek 2011