Charting a Course – Chapter 8: Conclusions and Recommendations

To achieve the policy outcomes of water conservation and efficient use of water by the natural resource sectors, we need in Canada — across all provinces and territories — a more comprehensive and innovative approach to water governance and management. Such an approach must incorporate strategies to improve our knowledge of how and what water is being used by the sectors, when it is required or will be required in the future, what policy instruments can more efficiently and effectively manage water allocations, and the state of water supplies and demands in the most at-risk regions and watersheds of Canada.

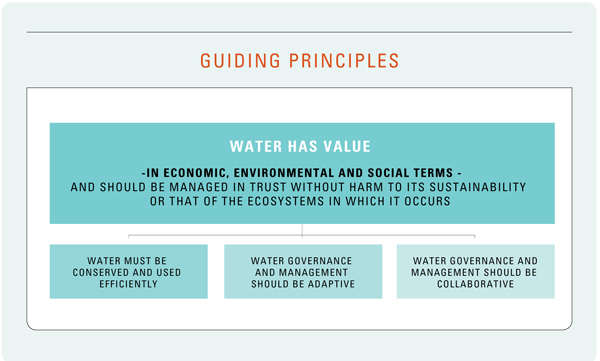

A comprehensive approach should be principles-based, and we recommend inclusion of the following principles to guide water governance and management:

- Water has value — in economic, environmental and social terms — and should be managed in trust without harm to its sustainability or that of the ecosystems in which it occurs.

- Water must be conserved and used efficiently.

- Water governance and management should be adaptive.

- Water governance and management should be collaborative.

The NRTEE’s research and discussions with experts and stakeholders have resulted in new insights and many conclusions. These conclusions have led us to provide a number of recommendations in the realms of water forecasting, policy instruments including water pricing, water-use data and information, and collaborative water governance. Our conclusions and recommendations were developed to help decision makers design the best policies and program for water management and governance for the natural resource sectors. And ultimately, they are intended to help achieve the outcomes of better water conservation and efficient water use.

WATER FORECASTS

CONCLUSIONS

A comprehensive and useful information base linking long-term economic growth to water use in Canada does not, for the most part, exist. This presents a significant gap in our knowledge of how water resources and economic development are linked. Without this knowledge, it is difficult to strategically plan for sustainable development of our natural resources.

Historical water use by the natural resource sectors demonstrates an improvement in water efficiency for most sectors, even in the absence of water policies to entice such efficiency gains. Water use requires energy — to pump, circulate, treat, and discharge it. Because of rising energy costs over the last decade, and through discussions with sector experts, we know that the natural resource sectors have found ways to reduce their energy costs, and in doing so, improve their water-use intensities. However we need to better understand the reasons for these improvements on a sector basis. This information is important in two respects: it will improve future water forecasts, which will in turn inform water allocation and management strategies; and it will inform how the natural resource sectors use policy instruments to reduce future water demands.

While most sectors currently pay very little to governments for the water they use, they nevertheless are incurring costs that drive water efficiency and conservation now. And while increased economic activity is causing increased water use in the natural resource sectors overall, historical trends of decoupling water use from economic growth are anticipated to continue, resulting in small overall increases in water use in Canada.

Even though the results of our scenario analysis reveal a potentially small overall increase in water intake on a national average, this result likely masks some regional challenges, in particular in oil and gas and agriculture. Further analysis on a regional basis is required to improve our understanding of where water demands are likely to increase substantially with economic growth.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- The federal, provincial and territorial governments should collaborate in the development and publication of a national water-use forecast, updated on a regular basis – a Water Outlook – the first to be published within two years. This could be led by a national organization such as the Canadian Council for Ministers of the Environment.

- Governments should develop new predictive tools, such as water forecasting, to improve their understanding of where and when water demands might increase. The information provided by forecasts will be important to inform water allocations and management strategies in the future.

- Recognizing that accurate water forecasting requires improving how we measure and report water-quantity data, governments and industry should work collaboratively to develop appropriate measurement and reporting requirements on a sector-by-sector basis.

POLICY INSTRUMENTS

CONCLUSIONS

Economic instruments (EIs) — either water charges or tradable water permits — allow the economic value of water to be revealed. They offer the opportunity to meet conservation and water-efficiency targets by transitioning current regulatory approaches toward instruments that are more efficient: water pricing or water trading. EIs have the potential to provide incentives and flexibility for water users by allowing them to determine their water use and adopt water-conserving technologies.

The use of a water charge seems the most likely option of the two, at least in the shorter term, and can be viewed as a transitional policy option. Licensing and water rental fees exist in all provinces and territories. This provides a solid foundation from which to move from a fee structure that is fiscally oriented, aimed at recovering administrative costs but providing little incentive to conserve water, to one that is incentive-based, where water charges send a signal that water is valuable and should be efficiently used and conserved. There are opportunities here to work within established management systems.

Trading water within watersheds represents a fundamental shift in water-management systems, and can be seen as a transformative option. With water trading, regulators must become market designers and enforcers while remaining focused on water-supply constraints. Existing legal, institutional, and administrative frameworks need to be assessed and reoriented to detach historical or riparian water rights, therefore allowing water to be reallocated through market trading. Political barriers can be significant when it comes to trading water rights. Real or perceived, concerns about stripping away long-standing rights, commoditizing water, and concentrating water rights in the hands of wealthier firms or sectors can be a barrier to trading. Water charges and water trading both face formidable challenges associated with their design and implementation. For water charges, the complexity of determining the value of water to society can make it very difficult to design and manage simple, transparent, efficient, and equitable pricing rules. A market for water trading requires a higher level of governance, increased capacity, and more knowledge. Therefore, water trading would likely be a more costly option to design and implement.

In the absence of government intervention, voluntary initiatives are likely to continue playing a role in improving water management across all sectors. While the effectiveness of such initiatives is still in question, past experience shows the promise of these approaches as they relate to measuring and reporting water use, and improving the transparency of industrial water management. Together, they help support industry’s “social licence” to operate. The sectors may therefore continue to generate interest in voluntary initiatives, as the financial community and customers are looking for more information on aspects of corporate social responsibility, including water management.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Recognizing that water policy strategies across Canada need to be flexible and responsive to changing water realities (changing hydrological conditions and increased water demands on regional and watershed bases) to avoid potential water conflicts, governments should take a phased approach to policy change:

- Ensure that enabling conditions such as legislation and regulation are in place. Because it takes years to develop and enact the legislation and regulation necessary for new economic instruments, jurisdictions that have not already done so should begin reviewing and working on the necessary legislative/regulatory and policy changes today if they want to strategically manage their water sustainability.

- Stage policy options, thereby allowing for adaptation to different circumstances. A comprehensive evaluation of economic and environmental conditions within a watershed must take place before determining which policy instruments are the most appropriate and the most likely to address water-allocation issues. Only then will governments be in a position to implement policy options appropriate to the situation within the watershed. Staging of options should be based on the existing or expected water constraints within a watershed. For example, watersheds experiencing existing or growing pressures on their water resources should take more aggressive policy approaches.

- Provincial and territorial governments should provide policy direction that is focused on more efficient water use and increased conservation, where required. To do so, jurisdictions should

- set conservation targets based on in-stream flow needs to ensure healthy aquatic ecosystems;

- set efficiency targets for the natural resource sectors to achieve;

- allow industry to demonstrate how they could achieve the efficiency targets on a voluntary basis first; and

- where necessary, send a long-term signal that water has an economic value by setting a volumetric price on water intake, in situations where water scarcity is or could be a real risk.

- Recognizing that further research is required on the use of economic instruments within the context of watersheds, governments intending to use EIs should evaluate their environmental, economic, and social implications, allowing for an informed discussion of trade-offs.

PRICING WATER

CONCLUSIONS

The NRTEE research shows the potential that putting a price on water has on achieving water reduction objectives, with modest impacts to most sectors and the national economy. Our scenario analysis, while preliminary in its development, is an important piece of new information looking at the relationship between water demands of the natural resource sectors and industry’s responsiveness to a price on water. Our analysis demonstrates that some sectors may be responsive to water pricing, and large efficiency and conservation gains could be achieved with small increases in the price of water. However, this research needs to be taken further, with better data sources, and discussed with the sectors to better understand the opportunities to change their water use in response to water prices. Specifically, we note that future analysis would be strengthened with additional sector and regionally-specific data that would allow for an assessment of the responsiveness on a price per unit of production basis.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Governments should research the relationship between water use and pricing needs before they implement water pricing on a volumetric basis. Specifically, they need to better understand the potential implications on sectors and firms. In order to do so, data on water-use needs to improve, to gain a better understanding of water intakes, recirculation, and recycling within facilities.

- The natural resource sectors should look closely at their water intake and where the costs rest within their use of water. Incorporating the “value” of water into operations may reveal opportunities for costs savings, through implementation of improved technologies or best management practices, possibly leading to overall water intake reductions.

- If a price is put on water use by the natural resource sectors, revenues should be directed to support watershed-based governance and management initiatives, rather than put into general revenue of the province or territory.

WATER-USE DATA AND INFORMATION

CONCLUSIONS

A lack of publicly available, reliable water-quantity data has negative implications for current and future water-resource management in Canada. Specifically, the lack of baseline water-use measurements hampers efforts to improve efficiency since improvement potential is difficult to estimate, actual improvements cannot be assessed, and incentives for reductions cannot be readily developed, implemented, or evaluated. Adequate water-quantity data would be required if jurisdictions opt to recover the costs of administrating water policy and water-efficiency programs and maintaining water-use databases. All provinces and territories would benefit from developing a “toolkit” of common water-quantity measurement techniques that could measure and quantify actual water intake and discharge volumes. Mapping information through an interactive media, similar to the National Atlas, is one possible tool, which could allow policy makers, technical experts, and the public to better understand and identify the geographic areas facing water resource concerns.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Provincial and territorial governments should establish demand-side data systems that have clearly defined reporting requirements for water licence holders. These systems would have common obligations to report provisions, contain defined time periods for reporting, and introduce enforcement programs to ensure reporting of water use by water licence holders.

- The provinces and territories, in collaboration with stakeholders and partners, should develop common measurement techniques to collect water-quantity data.

- The provincial and territorial governments, in collaboration with the natural resource sectors, should research the sector-specific future water data needs of their jurisdictions. These initiatives would help jurisdictions identify and develop data-management approaches and systems that have buy-in from the natural resource sectors.

- Governments at all levels should collaborate with partners and stakeholders to develop and integrate water-quantity data for use as a water-management tool at a local watershed scale. Provinces and territories should first develop integrated water-management tools within their jurisdictions at a finer spatial resolution, as it is easier to “roll-up” small-scale assessments to larger scales rather than to disaggregate an initial assessment performed at a larger spatial scale.61

- In collaboration with partners and stakeholders, governments at all levels, should develop protocols for transparent access to water data. Provinces and territories should continue establishing their own water-data portals. The federal government should develop a national web-based water portal, in collaboration with the provinces and territories, which also provides access to provincial and territorial water portals.

COLLABORATIVE WATER GOVERNANCE

CONCLUSIONS

Provincial governments need to clearly define the mandate, scope of activities, and role of collaborative groups as well as the role and importance of First Nations and the natural resource sectors in collaborative water governance initiatives. We also note the need to move toward the integration of land and water management in addressing many connected watershed challenges.

Three crosscutting themes arise from the research:

THE CONTINUED IMPORTANCE OF HIGHER ORDERS OF GOVERNMENT

Successful collaborative governance depends on strategic support from higher orders of government. The NRTEE notes that stakeholders often perceive a lack of guidance and/or support from governments. This is particularly interesting given the high degree of variability with respect to provincial/federal involvement, financial support, and oversight across the country. A central theme is the alignment (or lack thereof ) of municipal, regional, and provincial governments, collaborative watershed groups, and the public. Although focused on the watershed, collaborative water governance touches land use and other key planning processes, and cannot be conducted in isolation from them. When creating collaborative water governance partnerships, government agencies should remember that they must continue to play a key ongoing role.

THE IMPORTANCE OF RELATIONSHIPS

Building relationships and trust is central to the success of collaborative governance processes. Collaborative governance initiatives are both a space to build relationships, and entities dependent on these relationships. Their value is seen as being both formal (e.g., sharing data or holding regularly scheduled meetings) and informal (e.g., building friendships and understanding, knowing who to call with a question). This, in turn, highlights an important element of successful collaborative governance: sufficient time devoted to the process.

THE NEED FOR CAREFUL DESIGN OF COLLABORATIVE GOVERNANCE PROCESSES

Collaborative governance is a tool to be selected in particular situations, not a panacea for all water governance challenges. It is an excellent tool for conducting public outreach and education, for preventing potential conflict, and for bringing stakeholders together. On the other hand, collaborative governance initiatives need clear rules, guidance, and support from their respective provincial governments in order to “do their jobs well,” and they are not a replacement for strong provincial leadership. In fact, collaborative governance “badly done” — i.e., without stakeholder or government support, in a conflict-ridden situation, or not in the “true spirit” of collaboration — has the potential to make things worse, not better.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Governments should affirm the legitimacy of collaborative water governance and demonstrate that collaborative governance bodies have an important role to play. If governments choose to invest in collaborative processes, they must act on the recommendations provided by the collaborative process as much as possible and commit to provide formal feedback to the group when recommendations are ignored. Otherwise, participants from the natural resource sectors will lose confidence and leave the process, given the significant time and financial commitment for them.

- Governments must recognize that collaborative water governance structures require clear roles and responsibilities and well-defined accountability rules. Most people and organizations involved in collaborative water governance across Canada, including the natural resource sectors, believe that there is insufficient clarity about authority and accountability for decision making within the current frameworks. As a minimum, the Terms of Reference for the collaborative processes require a written description of roles and responsibilities. A more formal document would strengthen the accountability, and in some cases, governments may want to enshrine the governance structure into a new piece of legislation.

- Collaborative water governance processes should be developed and implemented in a coordinated manner with other planning processes and policies. Water governance is not only about water and cannot take place in isolation from other planning processes affecting and involving the natural resource sectors, such as municipal land use planning or forest management plans. As these processes operate at various scales and involve several orders of governments, policy alignment will require coordination between a number of governmental and non-governmental organizations.

- Governments should provide incentives for participation. Effective collaborative water governance requires the involvement of a broad range of stakeholders, including the major water users in the natural resources sectors. For collaborative water governance processes to become operating concerns in the natural resources sectors (rather than optional activities), government must identify them as a priority. This could be done by making participation mandatory, through regulation or as a condition of water licences.

FUTURE AREAS OF POLICY RESEARCH

In conducting our research, experts and stakeholders brought forward many issues related to water use by the natural resource sectors, of both a quantitative and qualitative nature. It is worth noting some of these issues, and pointing out that the NRTEE recommends that they should be further investigated as Canada continues to develop its natural resource sectors.

EFFECTS ON WATER QUALITY AS A RESULT OF NATURAL RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT

Most, if not all, of the natural resource sectors have some potential effect on the quality of the water they use in their production and operational activities. While some of these effects are well understood, emerging sectors, such as shale gas, are not well understood in the Canadian context and need to be assessed further.

UNDERSTANDING OUR GROUNDWATER

While the NRTEE’s research focused on surface water resources, we recognize the inherent link between many of Canada’s surface waters and groundwater. Our recommendations regarding the need for improved data and information of surface water extends to that of our groundwater resources. The NRTEE recommends that governments continue to prioritize the mapping of Canada’s aquifers in an attempt to better understand the groundwater supplies and the withdrawals that are taken from these sources.

WATER-ENERGY NEXUS

Through our investigation of water use by the natural resource sectors, it has become apparent that the relationship between water and energy is very important. As we noted in our first report Changing Currents, this linkage warrants further detailed analysis in Canada, especially as policies are developed for energy, water, and greenhouse gas reductions. A better understanding of these linkages will lead to more effective policy development.

_____________________

Footnote