2.0 State of Play – Facing the Elements

In a changing climate, the past is no longer a good guide to the future. Businesses that plan ahead can limit downside risks and take advantage of commercial opportunities, gaining an edge in the near and long terms.

Businesses and industry sectors already manage a range of business risks and opportunities, some relating to extreme and unpredictable weather. Is adapting to the risks and opportunities of a changing climate any different? How do businesses perceive their exposure to the risks and opportunities of climate change, and how are they managing the issue? Why should adapting to a changing climate be on the radar of business? What actually motivates businesses to take steps and invest in measures to build resilience today, and what could do so in the future? This chapter explores these questions.

2.1 ILLUSTRATING BUSINESS EXPOSURE

Business has always faced risks from climate variability and environmental change. For our resource industries that work on the “frontier,” planning for and adjusting to prevailing weather and seasonal climate is the normal way of doing business, and firms have amassed good practices to reduce exposure to physical and environmental risks. Eastern off-shore oil and gas businesses build platforms that withstand Atlantic hurricanes, and western oil and gas producers successfully operate under a wide range of climate conditions. Agri-businesses cope with floods and droughts and optimize production in response to changing weather forecasts. Forestry and tourism businesses are accustomed to dealing with environmental change, including natural disturbances like wildfires.

Yet there’s a difference between coping in the short-term by relying on past experience in a stable climate and preparing for continuous change over the long term. For example, the rail industry recognizes that it needs better technologies for managing avalanche risk to deal with changing snow conditions and that rising sea levels and related flooding risks in coastal estuaries will affect operations and siting decisions.12 Planning ahead for future impacts of climate change also means amending traditional management systems to accommodate greater uncertainty than what businesses are accustomed to, and doing so systematically. The prospect of increasingly intense hurricane seasons, for instance, could justify reinforcements of drilling platforms once viewed as too costly. And consider the economic and operational implications of the potential for both more severe and frequent drought and “unusually wet years” in the Prairies.13

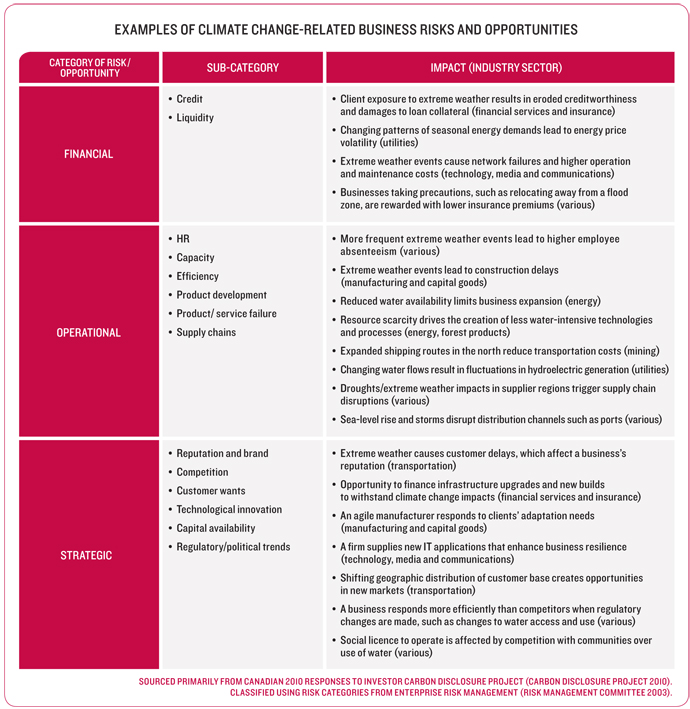

For firms beginning to evaluate what a changing climate could mean for their own business, Table 1 shows ways different industry sectors become exposed. Some risks are internal, others arise across supply chains, and still others relate to broader aspects of society like markets, stakeholder expectations, and the regulatory environment.

TABLE 1

Since we live in a global economy characterized by lean inventories, long supply chains, and just-in-time delivery, the potential for climate change to create systemic risks is not out of the question. The global climate is complex. Changes in one aspect of it, like warmer air temperatures, have cascading effects on other aspects, like numbers and frequency of heavy rain events and related flooding.14 The reality is that many different impacts of climate change — that materialize as sudden events or build up over time — could occur at the same time across different locations. In addition, interconnections across markets and societies make it hard to predict where, when, and how a situation could turn volatile, magnifying businesses’ exposure to risks posed by climate change. For example, a changing climate could complicate a business growth strategy that increasingly relies on an emerging economy to both supply inputs and buy goods and services. More frequent and volatile extreme weather events in that country could trigger supply-chain disruptions, reduce customer growth prospects, and shift customer preferences.

2.2 UNDERSTANDING CURRENT AWARENESS OF RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES

To understand business engagement in climate change adaptation in Canada, we analyzed two information sources on businesses’ perceived exposure to risks and opportunities from the physical impacts of climate change.

FIRST, we looked at publicly available responses by Canadian businesses to the Investor Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) from 2003 to 2010.[b] The CDP survey targets the largest businesses in terms of market capitalization. Its completion is voluntary, garnering an overall response rate of about 46% in 2010, with 37% of responses available to the public.

SECOND, we reviewed annual securities filings by 35 Canadian businesses across seven industries (chemicals and fertilizers, insurance, oil and gas, paper and forest products, pipelines, transportation, and utilities) with upward of $1 billion in market capitalization for 2008 and 2010. Publicly traded companies in Canada have long been required to disclose information that may be material to investors (i.e., information that a “reasonable investor” would consider in evaluating a business’s position). To explore whether Canadian companies see material risks stemming from the physical impacts of climate change, we assessed annual reports and annual information forms, including Management’s Discussion and Analysis (MD&A), as filed on the information system developed for Canadian Securities Administrators.[c]

THIS IS WHAT WE FOUND:

Canadian firms have a growing appreciation of the potential risks to their business from the physical impacts of climate change. Our analysis of CDP responses reveals that in 2003, 17% of Canadian businesses responding to the survey identified a perceived exposure to the physical impacts of climate change; however, by 2010, 56% of respondents said they were exposed to these risks.

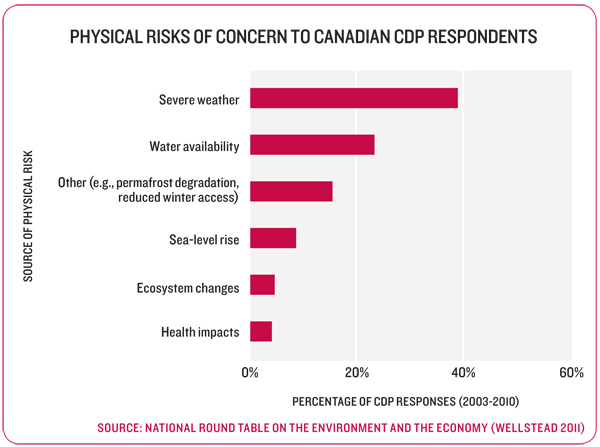

The most commonly identified risk is severe weather. By aggregating responses across all CDP survey years, and thereby smoothing out response variability over time, we were able to take a look at the kinds of physical impacts of concern to businesses. Firms are clearly aware of the potential for more frequent and severe weather events to damage existing infrastructure, facilities, or capital equipment, with 39% of respondents mentioning severe weather events as a risk to them. The impacts of potential shifts in run-off and precipitation patterns (23%) also receive relatively frequent mention. Figure 1 shows the types of impacts businesses are most concerned with, according to our CDP analysis.

FIGURE 1

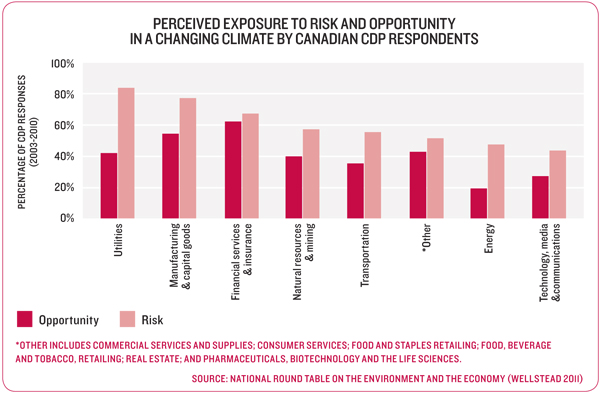

Businesses also see opportunities arising from the physical impacts of climate change. Identification of opportunities has grown between 2003 and 2010, and responses pooled over the eight-year period of analysis let us shed light on whether and how Canadian businesses perceive opportunities in a changing climate. Overall, 38% of Canadian CDP responses indicated the potential for opportunities to arise, mostly stemming from lower production costs, increased demand for goods or services, or reduced competition with respect to existing lines of business. Far fewer mentioned business opportunities related to new product areas and services, but those that did mainly pointed to new financial products and resource development opportunities in the Arctic. Perceived opportunities have shifted over time: in 2003, no Canadian businesses identified opportunities related to the physical impacts of climate change; but by 2010, 43% did.

Perceptions of a changing climate as a source of risk or opportunity differ by industry sector. Figure 2 shows the extent to which businesses see risk or opportunity from the physical impacts of climate change by industry sector, according to their CDP responses. For the most part, a changing climate represents to businesses a source of downside risk more so than opportunity. This is particularly the case for utilities, energy, manufacturing and capital goods, and transportation sectors where perceptions of risk outweigh opportunities by 20 percentage points or more. The financial services and insurance sector is the most likely to perceive opportunities related to the physical impacts of climate change. The three most represented sectors in the Canadian CDP responses are energy, financial services and insurance, and natural resources and mining. Here we offer general observations on each:

// FINANCIAL SERVICES AND INSURANCE: Banks and financial services firms tended to report both high levels of perceived risk (including types of risk rarely mentioned by other sectors) and high levels of perceived opportunity. CDP responses from this sector were the most comprehensive and thorough: they identified and discussed a range of risks and impacts and described their business implications.

// NATURAL RESOURCES AND MINING: Businesses’ responses in this sector reflected a moderate concern and attention to both risks and potential opportunities. These businesses were more likely to express specific issues arising from physical changes, such as impacts on international supply chains or impacts on foreign operations, reduced or limited access to facilities due to unreliable use of winter roads or routes, and potential opportunities in a warming Arctic.

// ENERGY: Businesses in this sector were the least likely to report possible opportunities arising from climate change and the second least likely to report exposure to physical risks of all the sectors. It was not uncommon for energy firms to register the significance of physical climate change risks lower than the risks posed by GHG emissions mitigation policy.

FIGURE 2

For the most part, the physical impacts of climate change do not register as material risks. Compared to 2008 securities filings, disclosure rates of risks related to a changing climate in 2010 show some improvement for utilities and transportation. Still, disclosure rates and quality continue to be limited: the analysis of 35 annual securities filings yielded few examples of material risks presented by a changing climate.[d] Three material risks were identified: potential damage to electricity generation facilities and revenue losses linked to shifts in water flows and wind patterns; disruption to rail operations, infrastructure and properties, and adverse impact on financial position and liquidity related to more frequent severe weather events; and threats to operations through storm-water flooding. Some businesses in the pipelines, chemicals and fertilizers, and utilities sectors disclose material risks to their business posed by severe weather, water availability and quality, and seasonality (a source of operational risk), but not in the context of a changing climate. Remarkably, insurance businesses provide no disclosure of how a changing climate could present material risks.

Businesses tend to provide much more information on how climate change could affect them in voluntary reports than in their mandatory securities filings. This finding comes from a comparative analysis of the 35 companies’ securities filings for 2010 with their CDP responses, when available. For example, companies in the chemicals and fertilizer sector provide little to no acknowledgement of risks from the physical impacts of climate change in mandatory filings yet describe the potential for sea-level rise to disrupt transportation logistics and port access in addition to longer growing seasons in certain markets in their CDP responses. Oil and gas companies discuss risks from physical impacts such as shifts in water availability, shorter windows of opportunity for production or exploration in “winter access” areas, and warmer air temperatures affecting the efficient operation of equipment, but only in response to the CDP questionnaire.

2.3 EXPLORING BARRIERS TO TARGETED ACTION

Business awareness of the risks and opportunities posed by climate change is growing world-wide, but concrete efforts to systematically and explicitly integrate these risks into business planning, practices, and investments is less apparent.15 In 2009, for example, Acclimatise concluded that the largest UK businesses had not yet adjusted their business risk governance systems to enable preparedness for future physical impacts.16 More recently, analysis of global CDP responses by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development revealed that fewer than one in ten businesses aware of risks and opportunities from a changing climate were managing them.17

To examine the situation in Canada, we conducted 27 semi-structured interviews with businesses and industry associations across ten industry sectors.[e] We acknowledge that the sample size and self-selection in interview participation makes our findings indicative rather than representative of Canadian business views. However, these interviews, combined with our CDP and financial disclosure analysis, as well as discussions at stakeholder sessions lead to these observations:[f]

Some confuse GHG emissions mitigation, adapting to GHG emissions mitigation policy, and adapting to future climate. Businesses demonstrate a clear understanding of the importance of mitigation, and are adept at reporting efforts to achieve emissions reductions and energy efficiencies. In contrast, some confusion exists about what “adaptation” is. We noted instances in which businesses included adapting to a changing energy landscape and emissions reductions requirements in their definition. A 2009 survey by Natural Resources Canada noted that of roughly 40% of businesses claiming to be taking measures to adapt, 73% of them described mitigation actions and only 18% described adaptation actions.[g],18

Businesses routinely adapt to severe weather events but the extent of action to adapt to longer-term and gradual impacts of climate change is unclear. Outside of a few “climate-sensitive” industry sectors, such as forestry, agriculture, and tourism, a dominant perception is that climate change impacts are an extension of those related to severe weather, and that these impacts are familiar and manageable. Our interpretation of these views is that businesses’ consideration of risks from climate change is incomplete. It’s possible that they do not fully understand the risks accruing from gradual changes in climate conditions, from impacts beyond the “factory walls” such as supply chain interruptions, or from the adaptive responses of the financial sector that include adjustments in insurance coverage and affordability. Interviewees representing agriculture, forestry and tourism sectors, in contrast, indicated that future climate change could lead to substantial transformation for their industries. One emphasized that “adaptation will eclipse any discussion about emissions mitigation — it will become the policy issue within the next three-to-five years.”19

Costs and uncertainty make transforming core practices and business strategy in anticipation of future impacts hard to justify. It’s evident that businesses fail to grasp the value of making adjustments and investments today to foster resilience to impacts that may or may not materialize in the long term, even when that same corporation would benefit from these adjustments. One interviewee summarized the challenge of making the decision to adjust core practices and business strategy as follows: “It is difficult to plan for risks that are 20 to 40 years out and even harder to justify spending money now on risks that people don’t understand.”20 Stakeholder discussions reinforced this sentiment by highlighting difficulties in translating data and information on climate change and its impacts into economic risks and opportunities for a given firm.

A reactive approach — that is, adjusting as physical impacts of climate change occur — is seen as sufficient. A common view is that climate change is one type of business risk, managed like any other through existing corporate risk management and business continuity practices. Not only is the perception that existing management systems are sufficient to manage risks related to climate change, but also that business can handle slow, gradual changes by adjusting practices incrementally — just as it has always done with any type of change or new risk. Some businesses view gradual, creeping changes like the entrance of invasive species, shifting agricultural growing zones, sea-level rise, and declining water flows as too distant in time to worry about within current business planning. Our CDP analysis also confirmed this by revealing few instances of Canadian businesses reporting that they developed or adjusted plans to specifically address increasing risks associated with a changing climate. And the situation was similar for responding to opportunities: while over a third of the total survey responses indicated that firms perceived potential business opportunities related to the physical impacts of climate change, few businesses indicated that they were engaged in business planning activities specifically focused on seizing these opportunities.

2.4 BUILDING A BUSINESS CASE

The effects of a changing climate are already evident in Canada and globally, and all firms — regardless of sector, location, and size — face both direct and indirect impacts to their business. Changing climate conditions and the resulting physical impacts (e.g., reduced water availability in some regions) can affect businesses’ financial, operational, environmental, and social performance. Businesses that proactively plan for a changing climate can avoid many of the worst effects of climate change and take advantage of opportunities.

The business case for each firm depends on a host of variables. For example, for Entergy, an electric utility that operates in the hurricane-prone U.S. Gulf Coast, the case for action hinges on preserving its customer base, the well-being of its employees and communities in which it operates, and billions of dollars in investment.21

However, an overall business case for acting in anticipation of impacts to come is clear for a number of reasons:

// THE CLIMATE IS ALREADY CHANGING; SOCIETY MUST ADAPT. society must adapt. Previous reports in the NRT’s Climate Prosperity series have clearly articulated that Canada and the world face continuing unavoidable change in climate conditions. Even if the world drastically decreases greenhouse gas emissions immediately, our environment, society and economy will need to cope with a changing climate for many decades as a result of emissions we have already put into the atmosphere. And, since reducing GHG emissions today will limit the speed and scale of climate change in the future, governments, communities, businesses, and households alike must take action to both adapt to the consequences of climate change already locked in and reduce future GHG emissions.

// BUSINESSES STAND TO BE DIRECTLY IMPACTED. Assets and supply chains, the health and safety of their employees, and the communities and environments in which they operate could all be affected.22 Some businesses are particularly vulnerable. These include firms that undertake activities sensitive to prevailing weather and climate, have complex supply chains, rely on long-lived fixed assets, or operate in environments that are at (or near) climate thresholds and transition zones (e.g., regions underlain by discontinuous permafrost). In a world of increasingly volatile weather, warmer temperatures, and shifting precipitation patterns, infrastructure and capital assets built to operate within design criteria and margins based on past climate conditions are at risk of failure. The impacts of climate change could increase the frequency by which design, operation, and safety thresholds are exceeded, imposing costs through maintenance and repairs, shortened asset lifespans, early decommissioning, or additional capital investment for new assets that may be necessary.

// BUSINESSES WILL ALSO FACE INDIRECT IMPACTS. Non-market forces such as policy and regulation and the activities of interest groups will significantly alter how businesses operate. The indirect impacts of climate change across businesses’ value chains are hard to ignore. Assessing the potential impacts of a changing climate for a business includes taking into account the position being adopted by investors, lenders, shareholders, insurers, and external partners like governments and communities. Stakeholder perceptions and expectations are likely to influence a business’s licence to operate and the regulatory environment, together with their reputation. A report by four institutional investors focusing on four climate-sensitive investment sectors stated that “climate change is now recognized as one of the most serious long-term challenges facing the investment community.”23 Some institutional investors have taken notice of these potential impacts on corporate value and actively encourage businesses to assess and disclose risks and opportunities of a changing climate as part of business strategy.24

// EARLY ACTION CAN BRING TANGIBLE BENEFITS. Businesses that move quickly to assess and manage the risks and opportunities of changing weather and climate can save money and position themselves to address evolving stakeholder expectations. Our recent NRT report Paying the Price: The Economic Impacts of Climate Change for Canada concluded that climate change could impose high costs on Canada and that small investments in adaptive measures could yield large savings.25 The benefits of adaptation are local, often accruing primarily to those fronting the costs.

In many cases, deferring adaptation, waiting for more and better information on future impacts, and relying on just-in-time solutions is more costly than taking a proactive stance.26 First, it’s often cheaper to incorporate climate change into capital investments upfront than to retrofit later. Second, building internal capacity to deal with climate change takes time. Developing the human resources, governance, and skills to effectively manage new challenges cannot be done overnight. Third, reacting with one-off adaptation actions to weather or climate events leaves businesses exposed to long-term shifts. Fourth, technology needs to be built over time; the “solutions” to all of our adaptation problems aren’t readily available on the market. Finally, investments to manage business risks from a changing climate can reduce businesses’ vulnerability to current weather, water, and other environmental risks.

// CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION DOESN’T HAVE TO BE COMPLEX OR COSTLY. By integrating risks from climate change alongside other business risks, firms can build on existing expertise in their organization — among sustainability, procurement, business continuity, and environmental managers — and embed adaptation thinking within existing management systems. Several low and no-cost measures can be taken to improve the performance of infrastructure and assets as well as save businesses money. To deal with rising flood risks, for example, businesses can re-locate critical equipment and objects of high financial value to upper floors or higher elevation. Water efficiency measures are a low-cost response to seasonal water stress. Natural ventilation and shading offer a cheap solution for businesses in cities exposed to extreme heat, with the added benefit of conserving energy.

// FIRST MOVERS WILL GAIN A COMPETITIVE EDGE. A changing climate presents commercial opportunities for businesses27 — opportunities to access new markets, develop new technologies and products, and stay ahead of regulation. These can be a source of competitive advantage — or disadvantage if a competitor gets there first. Businesses that are able to supply climate-sensitive goods (e.g., by growing crops that are less viable elsewhere) or that have adjusted their planning and decision-making processes with climate change can gain a competitive advantage.

2.5 KNOWING THE MOTIVATIONS FOR ACTION

As private-sector engagement on climate change adaptation is in its early stages, learning from the experiences of businesses already implementing strategies to prepare for future physical impacts is key. Direct dialogue with businesses is necessary to understand motivations, barriers, and enablers. From our thirteen case studies, we conclude that four factors stand out as motivations to adapt to climate change today.[h] These are entry points for governments and other actors seeking to engage business on the issue.

// SEEING IMPACTS FIRST-HAND: Many “early adapters” have experienced the impacts of climate change firsthand. When those impacts are costly or tarnish a firm’s brand and reputation, businesses tend to prioritize adaptation. First-hand experience transforms the issue of climate change from an abstract, distant problem to a real, imminent risk to performance and operations.

// UNDERSTANDING THE CONNECTION BETWEEN PHYSICAL IMPACTS AND BUSINESS SUCCESS: Early adapters understand how direct and indirect impacts of climate change affect businesses’ ability to meet certain objectives, be they financial targets, service level agreements, fiduciary responsibilities, or professional standards. Thus, an understanding of these interactions tends to be a pre-condition to taking the issue seriously.

// TUNING IN TO STAKEHOLDERS: Businesses that understand sustainability as a business imperative recognize climate change adaptation as a business performance issue. Forward-looking businesses are attuned to emerging global trends like heightened levels of scrutiny by investors, governments, banks, insurers, and NGOs regarding business climate change risk management and adaptation.[i] The potential for climate change to create or exacerbate tensions that lead to reputational damage, through impacts on the environment and local communities, is also a consideration. Businesses located in resilient communities will face fewer climate-related business disruptions caused by employee absences and interruptions in local supply chains.28

// EMPLOYING GOOD RISK MANAGEMENT: Distinguishing climate change adaptation from overall business risk management is often difficult. The distinction is artificial or arbitrary because firms view risks from climate change alongside other business risks. Adapting to climate change will require changes in the way firms do business, but firms with strong risk-management cultures are well positioned to implement adaptive measures that further enhance business risk management. The inseparability of adaptation and risk management also means that tracking private-sector progress in adapting to climate change will not be easy.

In addition to the four motivations of relevance today, another four loom on the horizon. These external pressures are likely to increase the uptake of adaptation in the future.

// REGULATION, LEGISLATION, AND STANDARDS: Some countries have introduced requirements to integrate climate change risk and adaptation within business planning and projects.29 Codes, standards, and guidelines shaping professional practice are beginning to embed future expectations of climate change to encourage behavioural change.30

// LEGAL LIABILITY: Legal professionals are beginning to consider risks from changing climate as “reasonably foreseeable.” Individuals with fiduciary responsibilities (e.g., company directors, trustees) and professional advisors (e.g., engineers, environmental and social impact consultants) may be failing in their duties if they do not proactively consider and disclose such risks.31 Although case law does not yet exist, litigation or the threat of litigation based on negligence or nuisance charges, for example, could drive adaptation.

// INSURANCE PRICING AND AVAILABILITY: Global insured losses have increased roughly five-fold since 1980, with climate trends partly to blame.32 A rise in claims often means a rise in insurance premiums, affecting businesses’ bottom-line. Insurers may also stop covering certain perils in high-risk areas.33 The threat of this removal provides an incentive for society to take adaptive measures at large, so as to maintain affordability and availability of coverage. Businesses that take adaptive measure to reduce their exposure could see lower insurance costs relative to competitors’.

// ACCESS TO CAPITAL: To date, short time horizons for investor decisions and a focus on regulatory risk from GHG emissions mitigation policy have limited investor pressures relating to climate change risk, putting a premium on adaptive measures with short payback periods. That might soon change. In 2010, 78% of North American asset managers responding to an international survey claimed to have considered the physical impacts of climate change in their investment decisions.34 Lending institutions are also beginning to integrate climate change impacts into credit risk analysis and updating their due diligence procedures accordingly.35

[b] The Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) is an international effort to track corporate progress on managing climate change risks and opportunities. Relying on voluntary responses to an annual survey of open-ended questions to large corporations, the CDP has amassed an extensive database of business responses since 2003. The NRT analysed 392 publicly available survey responses including 75 responses from 2010. The complete analysis is available upon request (Wellstead 2011).

[c] Report available upon request (Ceres and Climate Change Lawyers Network 2012).

[d] The sample size of 35 was enough for the Ontario Securities Commission to assess environmental reporting of Ontario issuers in 2007 and conclude that climate change disclosure was largely boilerplate and insufficient (National Instrument 51-716).

[e] Report available upon request (Deloitte 2011).

[f] Observation about the extent and quality of private-sector action on adaptation could understate actual levels of engagement. Firms tend to want to preserve the confidentiality of their climate change risk assessment and management activities. Some perceive risk disclosure as a competitive disadvantage. Others are concerned about disclosure of climate change risks to shareholders. Still others are concerned that stakeholders might interpret a public position on climate change adaptation as a cavalier attitude toward GHG emissions mitigation. The inseparability of adaptation from good risk management also presents challenges in drawing conclusions about the business adaptation.

[g] This sample size yields results that are accurate to within 5.6% 19 times out of 20. Businesses surveyed were primarily those seen as highly exposed to climate change including the resource sectors, tourism, and transportation so the survey is not representative of all Canadian businesses.

[h] The full case studies are available for download from http://…

[i] An example of the ascendance of adaptation as a policy and economic issue on the global stage is the World Economic Forum’s 2012 Global Risks Report. It highlights the failure of climate change adaptation as one of the most likely and impactful risks facing governments and businesses globally (World Economic Forum 2012).

[12] Carbon Disclosure Project 2010; B. Burrows 2011

[13] Sauchyn 2010

[14] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2011

[15] Acclimatise 2009; Agrawala et al. 2011; PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (U.K.) 2010

[16] Acclimatise 2009

[17] Agrawala et al. 2011

[18] Environics Research Group 2010; Horton and Richardson 2011

[19] Deloitte 2011

[20] Deloitte 2011

[21] National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy 2012. Facing the Elements: Building Business Resilience in a Changing Climate (Case Studies)

[22] Firth and Colley 2006; Sussman and Freed 2008

[23] Insight Investment et al. 2008

[24] Investor Group on Climate Change 2012; Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change 2010

[25] National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy 2011

[26] Hallegate, Lecocq, and de Perthuis 2011; Acclimatise 2009; GHK 2010

[27] UK Trade & Investment 2011; GHK 2010

[28] United Nations Global Compact et al. 2011

[29] Ministère de l’écologie du développement durable des transports et du logement 2011; United Kingdom 2008;

Cameco case study in National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy 2012

[30] Canadian Institute of Planners ND; Engineers Canada 2009; Canadian Standards Association 2008; International Council on Mining and Metals 2009

[31] Koval October 27, 2011

[32] Robinson October 27, 2011

[33] LeBlanc and Linkin 2010

[34] Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change et al. 2010

[35] World Bank Group Global Environment Facility Program 2006; National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy 2012