Paying the Price – Coastal Areas

Canadians living in coastal areas are accustomed to the hazards of shifting sea levels and storm surges. Climate change will exacerbate existing risks, exposing 3,000 to 13,000 more homes to flooding by mid-century.

Canada has a vast coastline stretching 243,000 kilometres along three marine coasts. One in six Canadians lives within 20 kilometres of a marine coast.44 Coasts are an important source of recreation and livelihoods for many more. Coastal communities have a long history of contending with the hazards of flooding and erosion, but climate change is a new force that heightens risks to people, property, and the environment along coastal areas.

Canada has a vast coastline stretching 243,000 kilometres along three marine coasts. One in six Canadians lives within 20 kilometres of a marine coast.44 Coasts are an important source of recreation and livelihoods for many more. Coastal communities have a long history of contending with the hazards of flooding and erosion, but climate change is a new force that heightens risks to people, property, and the environment along coastal areas.

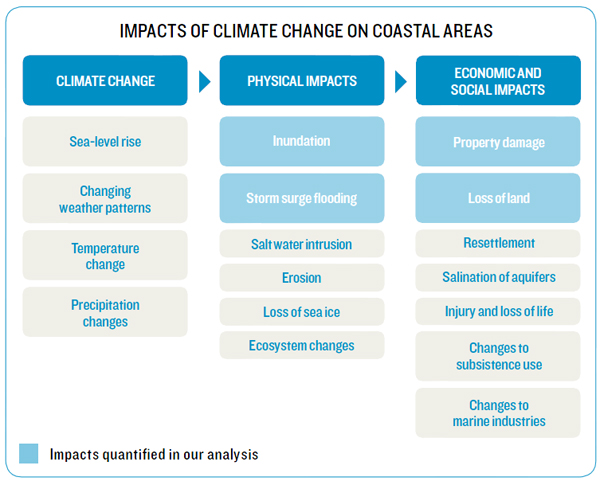

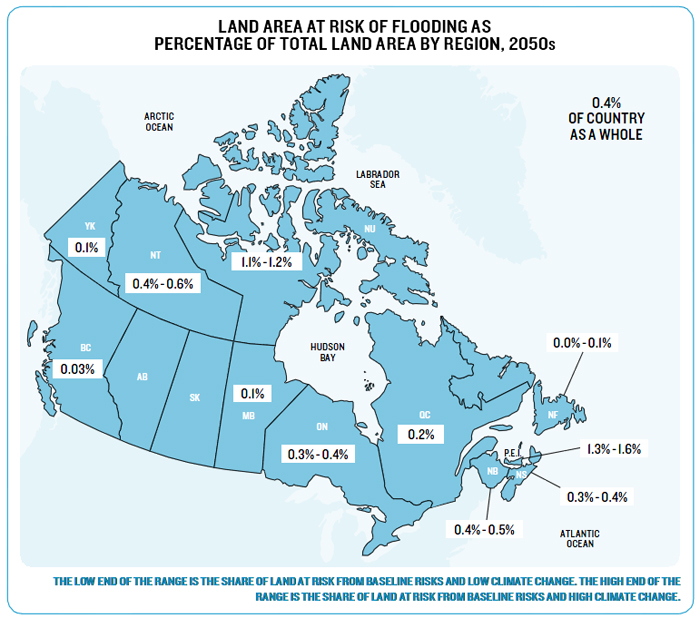

In a changing climate, the combined effects of accelerated coastal erosion, sea-level rise, and a greater frequency and intensity of storm surges could lead to permanent loss of land, temporary flooding, freshwater salination, damage to property, and disruption of key economic activities, among other impacts. Our understanding of the way that climate change could impact the coasts has recently improved. A nationwide study assessed Canada’s sensitivity to sea-level rise and found that one-third of our coastline is moderately or highly sensitive including 80% of the Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island coasts. The high concentration of people and expensive infrastructure in Metro Vancouver make this area particularly vulnerable. A few local and regional studies have assessed the impacts and costs of climate change for built infrastructure and homes, with most of them focusing on the East Coast. Beyond this, little research exists estimating the likely costs of climate change for Canadian coastal areas; this study will begin to fill that gap.

COASTAL FLOODING IMPACTS

-

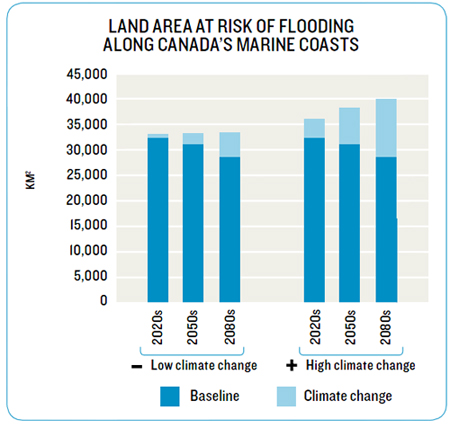

By the 2050s, in a given year, between 33,000 and 38,000 square kilometres (km2) of land will be at risk of flooding, with between 2,000 and 7,000 km2 of this area at risk due to climate change

-

Impacts are uneven across regions.

-

By the 2050s, in any given year, 16,000 to 28,000 dwellings will be at risk of permanent flooding from sea-level rise and temporary flooding from storm surges.

-

The majority of dwellings at risk are in British Columbia — about 8,900 to 18,700 by the 2050s

ECONOMIC IMPACTS

-

The annual cost of flooding of dwellings due to baseline risks and climate change could be $4 billion to $17 billion by the 2050s.

-

In absolute numbers, most of these costs are associated with dwelling damages in British Columbia

-

Per capita costs are highest in Nunavut, British Columbia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island.

-

Overall, these costs could represent 0.2% to 0.3% of Canada’s GDP each year by the 2050s while cumulative costs over the century could range from $109 billion to $379 billion using a 3% discount rate.

ADAPTATION STRATEGIES

Strategies to adapt to sea-level rise and the risk of storm surges are well known and fall into three broad categories: retreat, accommodate, and protect. “Retreat” involves moving away from vulnerable areas, “accommodate” involves, for example, redesigning homes and changing land use practices in a way that copes better with flooding and saltwater intrusion, and “protect” includes natural and engineered coastal defences to reduce flooding.

Our goal was to assess the cost effectiveness of two adaptation strategies of national application:

(1) Climate-wise development planning: The first strategy prohibits future construction in areas expected to be at risk of flooding by 2100 in a high climate change scenario. In this proactive strategy, the number of dwellings at risk of flooding stays at current levels, with existing dwellings being rebuilt following storm surges. No additional growth is allowed in these areas.

(2) Strategic retreat: The second strategy entails a gradual abandonment of newly flooded areas. That is, we assume that the flooding takes place and the reactive adaptive response is to relocate to a safe area.

Both adaptation strategies reduce the costs of climate change but strategic retreat yields benefits one order of magnitude higher than climate-wise planning. This is because in the climate-wise planning strategy, existing homes that are flooded by storm surges continue to be rebuilt over and over during the century, accumulating costs each time. With a policy of strategic retreat, damaged homes are abandoned and the price of rebuilding them is invested instead into homes in less risky areas.

When both adaptation strategies are pursued in combination, they could lower the cumulative costs of climate change impacts down to $1 billion to $6 billion over the century. Using climatewise planning and strategic retreat in combination, cumulative damages are just 3% to 4% of the costs without adaptation to climate change.