5.3 Key Actions

Framing the Future: Embracing the Low-Carbon Economy

STIMULATING INNOVATION

Innovation is one of the most important enablers of a low-carbon economy. Two trends in particular speak to the necessity for innovation in the low-carbon context: (1) intensified global competition and (2) continued and accelerated degradation of global ecosystems. As international competition increases, greater product/ service differentiation will occur, and carbon intensity is already emerging as an important performance metric. The global economy is growing to meet the increased needs of an expanding population, and there is a need for less resource-intensive and environmentally damaging methods of production to permit the continuation of economic growth. Innovation is essential to driving this change.

Just as Canada needs to reframe the traditional model of economic growth and prosperity to integrate a low-carbon focus, it needs to do the same for innovation policy. Although businesses implement innovations, governments shape the environment within which innovation occurs.100 Our research and stakeholder discussions indicate the need to sharpen the focus of Canada’s innovation agenda: an innovation agenda that is aimed at developing a stronger, more prevalent clean technology, or more specifically, LCGS sector, absolutely necessary if Canada is to advance toward a low-carbon economy. While innovation writ large is broadly a federal and provincial priority, low-carbon or cleantech innovation is only evident as a clear strategic priority for a limited number of provinces.d Setting an innovation policy agenda that is closely tied with clean and/or low-carbon technology will go a long way toward stimulating innovation. We see the following actions as priorities:

// To spur private sector innovation, governments must signal their commitment to achieving low-carbon objectives. Signals can take many forms, but could include policy instruments such as clean energy targets, standards for cleaner fuels, and more stringent energy efficiency requirements in building codes. With clear, sustained signals from government, investors would be more confident in supporting innovative ideas that move low-carbon technologies out of the labs and into the market.

// Policies that provide both “supply-push” and “demand-pull” will be necessary. An example of a demand-pull policy instrument is a feed-in tariff (FIT) program. An example of supply-push policy instrument is a tax credit for certain types of R&D. Canadian LCGS innovators could use more “push” in the form of organizations such as SDTC that provide both direct funding for demonstration projects and technical assistance and support. The need for additional organizations of this type is unclear, but long-term and expanded funding to existing organizations could go a long way in addressing unmet needs. The need for additional “pull” to increase demand for innovation is also apparent.101 In providing direct funding to support low-carbon innovation, Canada should be focused and seek to identify and support key strategic market niches. China, Korea, and others have created huge barriers to entry in the solar and wind markets through support to their respective manufacturers and exporters. Rather than attempting to compete head-to-head in these well-developed sectors, Canada should be investing in less developed and strategically important sectors such as CCS, and building on its existing manufacturing base and expertise in such areas as clean automobile manufacturing where there is a clear strategic benefit going forward.e Building on existing strengths in Canada’s resource base and areas of expertise, positions the country well to compete.

// Governments need to review and streamline innovation funding frameworks within which innovation occurs. Some in the innovation field have noted that overly burdensome regulations and policies often drive innovators to other countries to take their ideas to pilot or full scale.102 They have also noted that government support is frequently scattered under numerous federal and provincial programs with access requiring significant investment of time, effort, and resources. This presents a particular challenge for SMEs that form the majority of low-carbon innovators in Canada. It may be possible to address some of the noted challenges by reviewing policy and regulatory frameworks related to innovation and financing low-carbon technologies to ensure that they are efficient and yet robust enough to support development of the sector.

// Establishing innovation clusters could help narrow current gaps between innovators, particularly SMEs, potential users of the innovation, and investors. Although innovation clustersf are in their infancy in Canada, there is a need to quickly develop and support them to address these two key challenges, facilitate the exposure of their ideas and innovations to a global audience, and bring in the expertise and resources needed to attain the next level of development.

MOBILIZING INVESTMENT

The low-carbon transition requires investment in innovation across the full spectrum from technology research and development to demonstration and ultimately deployment. Investment in the physical infrastructure that supports the uptake of innovative products and processes is also critical. The scale of this investment — the investment required to drive the low-carbon transition such that it prevents dangerous climate changeg — is sizeable. The International Energy Agency estimates that an incremental annual investment of $158 billion in the decade from 2011 to 2020 and $1.1 trillion annually by 2035 will be required to achieve a global emissions pathway with a reasonable chance of limiting global average temperature rise to 2°C over pre-industrial levels.103

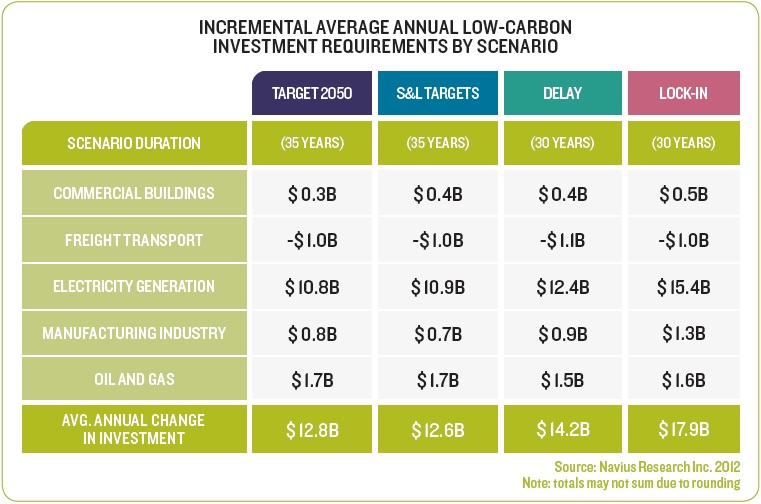

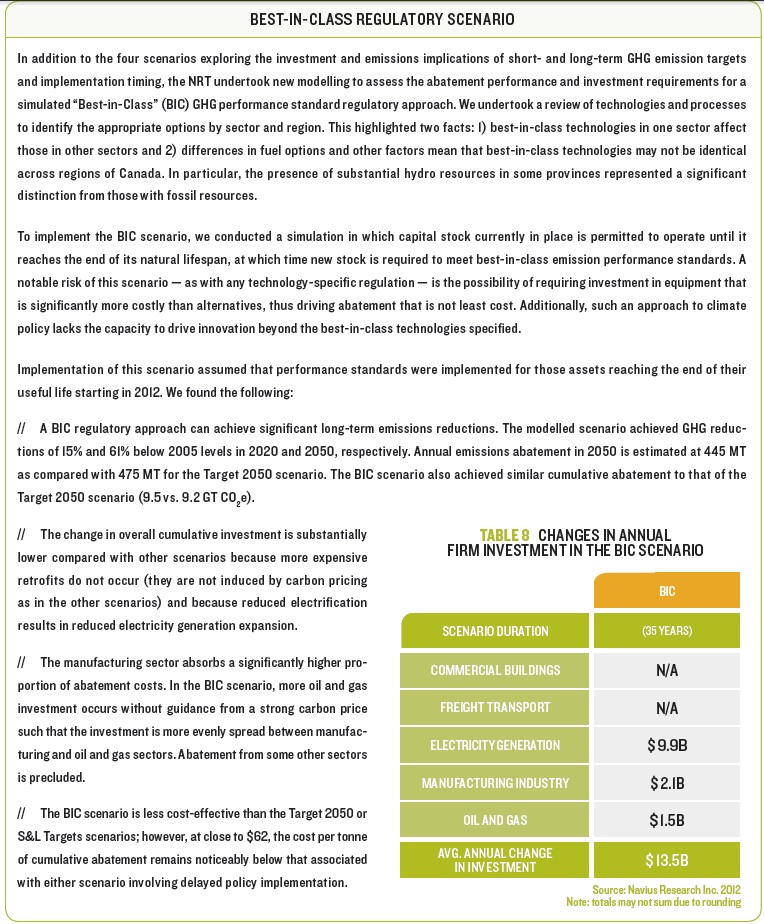

Canada needs to significantly step up its low-carbon investment with a focus on electricity infrastructure and the oil and gas sector. We estimate that for Canada to reduce GHG emissions by 65% below 2005 levels in 2050, annual investment on the order of $13 to $17 billion (Target 2050 and Lock-in SCENARIOS, respectively) could be necessary in addition to that already anticipated under existing and proposed policy measures.h Table 7 presents the forecasted investment requirements by scenario and sector (additional analysis concerning estimated investment required under a simulated regulatory approach is presented in Box 6). Roughly 85% of these annual amounts (i.e., between $11 and $15 billion) will need to be allocated to the electricity sector. For context, between 2000 and 2010, annual investments in the electric power sector averaged $12 billion.104 This means that Canada would need to roughly double the investment rate for the foreseeable future to meet the specified emissions reductions. Incremental investments modelled for the oil and gas sector are also noteworthy, amounting to $1.6 to $1.7 billion per year (or a 4–5% increase over current levels). This investment is largely focused on CCS. Additional investment in energy efficiency improvements, alternatively fuelled equipment, and building-shell retrofits in the commercial sector average between $360 and $560 million per year. Switching from road transportation to rail freight results in reduced investment requirements between $1.0 and $1.1 billion; however, the changes to investment in freight transport embody some additional uncertainty due to the infrastructure requirements of expanded rail service. Overall, the extra private sector investment amounts to an increase of between 5% and 8% per year over current levels, focused largely in the electricity and oil and gas sectors.

Table 7

Patient and risk-tolerant capital needs to be made available to Canadian LCGS entrepreneurs to allow them to succeed. One of the most significant challenges to innovators, particularly SMEs, is a lack of access to risk capital — in some cases the barrier is venture capital, in others it is an issue of significant project financing required for full-scale developments. Related to this is the challenge of time required for an innovative idea to come to maturity; it typically takes between 10 and 15 yearsi to reach commercial maturity which means that the availability of patient, risk-tolerant capital will be a key driver to the LCGS industry’s success. Government policies must help de-risk the financing of new innovative technologies and ideas to significantly improve commercialization of low-carbon technologies. While the Canadian government continues to fund innovation and has recently placed greater emphasis on early-stage risk capital105, additional funding geared specifically toward LCGS would be helpful.

Box 6

Beyond putting in place the essential conditions for low-carbon growth and establishing policy certainty through clear economic signals in particular, action is required on the part of both governments and the private sector to succeed in meeting the necessary scale and pace of investment. We have identified two key areas for action:

Governments and financial institutions need to work together to substantially increase access to capital. The substantial investment required to finance the low-carbon transition requires deploying a combination of public- and private-sector capital at greater levels than today. While the public sector’s continued role is critical, particularly in investing in areas of significant provincial, regional, or national interest, or R&D where the spinoff benefits are large, private-sector sources of capital will need to play an increasingly prominent role going forward. For this to occur, a greater diversity of sources of capital is required than is available today. This involves reaching out and creating ways for those who currently are not investing in low carbon — including untapped sources of capital such as institutional investors (e.g., pension and insurance funds) and even individual investors to do so.

To increase access to these alternative sources of capital, financial institutions need to develop and popularize new vehicles for low-carbon investment. Secondary markets for low-carbon project finance debt packaged as “green bonds” could provide banks with the ability to make additional loans and create a promising growth area.106 For broad adoption, green bonds (and other low-carbon securities) would need to adhere to standards that provide investors with certainty about the underlying investments.107 Leases for energy-efficient equipment also have significant potential. In addition to requiring no up-front costs from the purchaser, leases provide the opportunity for aggregation of projects into larger quantities more suitable for debt financing through partnerships with utilities or banks.108

New approaches to financing are also required to reduce transaction costs due to project size and due diligence requirements. Low-carbon infrastructure and technology investments tend to be fragmented and unstructured, consisting of a large number of small projects requiring individual financing rather than a small number of large, more structured projects.109 At the same time, requirements for due diligence — regulatory, technical, commercial and financial — tend to be similar, leading to comparatively high transaction costs. This frequently renders the projects unsuitable for financing by large corporate and investment banks despite the potential benefit from their in-house expertise. The development of tools and products that aggregate both the risk and the financing requirements into larger, more structured transactions could lower overall transaction costs and provide an entry point for larger financial institutions.

Banks and other financial institutions need to strengthen their capacity to perform risk assessments of lowcarbon technologies and projects.110 Low-carbon technologies tend to be complex and relatively speaking, immature, leading investors to attach greater risk to LCGS investments.111 Many low-carbon investments also have long-term horizons with respect to payback periods and investors require the financial return on their investments to be guaranteed over this time frame. In addition, revenue streams for low-carbon technologies are typically more complex to estimate than traditional technologies, compounding the risk attached to them. For example, the intermittent nature of many renewable energy sources increases the uncertainty associated with the revenue stream. To better understand these added dimensions of investment risk and to facilitate the development of customized investment vehicles structured to mitigate such risks, banks and other financial institutions need to increase their advisory capacity on technical, regulatory, commercial, and financial aspects of low-carbon technologies and projects.112 Developing capacity to fairly assess the risk of these investments is of particular importance with respect to attracting investment by institutional investors such as pension and insurance funds, which tend to have low levels of risk tolerance.113,114

Governments need to be open to providing incentives to encourage low-carbon investment. Incentives could balance the risk-reward ratios for low-carbon investment. Where perceived risk is high, balancing risk-reward ratios is necessary to improve the financial attractiveness of investments and to generate the desired levels of private sector investment.115,116 In some instances (for example with renewable energy technologies where grid parity has not yet been attained), support may be required for the development or introduction of emerging low-carbon technologies. Direct subsidies (e.g., feed-in tariffs) are often used in the absence of stability and clarity with respect to carbon markets.117 Other methods by which public funds are used to leverage private investment in low-carbon technologies include capital gains tax credits (direct equity or funds), tax-equity/debt schemes, and matching participation in venture capital equity investments. Such use of public funds can make sense where public spinoff benefits (e.g., from early stage R&D) are expected or where long-term benefits of initial investments are significant (e.g., increased deployment of renewable electricity technologies [RETs] brings them closer to grid parity) and would not be otherwise valued in private decisions (i.e., where there are specific market failures). Such incentives should be subject to regular review, keeping in mind requirements for long-term policy certainty and the principle of providing a level playing field across all technologies.

Incentives could also address barriers to low-carbon investments by Canadian households. High up-front costs can be a major barrier to consumer purchases of renewable micro-generation, electric vehicles, or low-carbon buildings, despite net savings over the lifetime of these technologies.118 Reducing up-front costs through low-interest loans, leases, or special mortgage arrangements would encourage purchasing decisions with carbon impacts in mind. Several of these programs are in existence in North America, but in Canada, the coverage of these programs is incomplete, and the strength of existing programs can be increased.

ENHANCING ACCESS TO LCGS MARKETS

Trade is and will continue to be critical to Canada’s prosperity. Trade related to Canada’s traditional, resourceoriented economic base and to low-carbon goods and services are both important. Ensuring access to key LCGS markets will support the growth of the low-carbon industrial base. Undertaking targeted activities, strengthening the international brand and, removing sector-specific barriers to trade are key strategies to pursue on a priority basis. A final priority lies in reducing the carbon intensity of the resource-oriented component of Canada’s economy; its continued success and access to global markets is at stake if Canada doesn’t act on this priority.

The federal and provincial governments should step up their roles in facilitating Canadian access to global LCGS markets. Canadian companies already target international markets disproportionately to the domestic one for two reasons: the small size of the domestic market and the absence of domestic signals to stimulate LCGS uptake. Access to global LCGS markets is currently inhibited by limited opportunity for domestic demonstration and by gaps among innovators, investors, and potential users of new products or processes. Governments need to make it easier for Canadian companies to tap into the growing global demand for LCGS. Key actions are as follows:

// Engage in international diplomacy to build the broad conditions necessary for investment and trade in Canadian LCGS. Canada should continue to actively participate in bilateral and international efforts to build capacity and remove barriers to investment in other countries. Tackling regulatory, policy, and technical barriers to the adoption of low-carbon energy applications in developing countries, in particular, not only encourages the flow of investment toward low-carbon energy provision but also opens up markets for countries that supply LCGS.119

// Proactively participate in the formulation of standards and labels of critical importance to Canadian exports. Canada should, for example, work to get a low-carbon fuel standard taken up by ISO for consistent application across states. Efforts to get hydropower recognized by U.S. federal and state governments as eligible for satisfying renewable portfolio standards requirements would position Canada’s electricity sector to benefit from access to premium rates for electricity exports.

// Convene stakeholders in LCGS innovation and promote LCGS sectors internationally. Governments can act as conveners to close the gaps between innovators, investors and users of innovative technology, particularly when it comes to SMEs. SMEs are leading low-carbon innovation in Canada. Our discussions with stakeholders suggest that their chances of success in global markets would greatly improve by connecting to and collaborating with large corporations that provide access to resources and expertise to help with commercialization. Governments are well situated to foster these strategic collaborations. Internationally, an expanded trade promotion and convening role by the Canadian government would support growth of Canada’s LCGS sectors. Such a role would involve linking up the strengths of Canada’s innovation with emerging international demand and potential sources of international finance. Benefits to Canadian innovators include reduced time, effort, and expense to gauge international interest and potential partnerships, which is important given the limited opportunity for domestic demonstration.j Indirect government endorsement of Canadian LCGS innovations would also benefit Canadian companies. Though not a standard requirement in dealing with most industrialized economies, government backing can be critical to sealing a deal in some emerging economies. The kind of government support described here will require the federal government to maintain a comprehensive global awareness of technology and innovation needs, as well as an in-depth and current understanding of solutions being developed within Canadian LCGS sectors.

// Put in place domestic procurement policies and technology verification programs. Canada’s small market and low risk tolerance when it comes to technology adoption means Canadian entrepreneurs often seek out international markets to prove the viability of their products and services before ever entering the domestic market. The added effort and expense by Canadian entrepreneurs to go international is incurred despite the noted preference of international purchasers for domestic demonstration. Domestic low-carbon technology testing, evaluation, and validation through government procurement and the development of a rigorous and internationally recognized low-carbon technology verification program (e.g., the U.S. EPA’s Environmental Technology Verification program) would provide significant support to Canadian firms.

The federal government needs to strengthen Canada’s international “brand,” particularly on climate policy. Canada’s brand is a form of currency in itself, influencing the ability of Canadian firms to trade and invest internationally, and affecting the inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI). Canada’s domestic and international climate policy positions and the communication of those positions on the international stage shape perceptions of Canada on a host of other issues and topics. The reality is that Canada is currently subject to substantial international criticism over climate policy and fossil resource development.k This has the potential to jeopardize trade and investment related to Canada’s current heavily resource-oriented economic base as markets begin to discriminate and investors begin to hedge against climate-related risks.

Improvements to Canada’s brand will come from actions that elaborate and demonstrate the country’s commitment to reduce GHG emissions and build capacity to engage domestically and internationally on climate change policy. This could include building effective and realistic pricing of carbon to meet current and future goals; developing and communicating clear, transparent, and realistic plans to meet Canada’s internationally-pledged target for 2020; and establishing a clear GHG reduction target for 2050. Canada should also seek opportunities to build on its strengths in the financial sector and its commitment to providing “fast start financing” (under the Copenhagen Accord and Cancun Agreements) as a contribution to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) Green Climate Fund. Canada should continue contributing to bilateral and regional initiatives, such as the multi-lateral commitment tackling short-lived climate pollutants.l

Federal and provincial governments should remove sector-specific barriers to trade. Where illegitimate trade barriers exist and Canada has a long-term interest in maintaining the viability of a strong sector, the federal government should consider measures available to it under international trade law. For example, the U.S. recently enacted countervailing duties to address alleged “dumping” of solar PV equipment by Chinese manufacturers. Where interprovincial barriers to trade exist, provinces should collaborate to remove them. For example, domestic content requirements in Québec and Ontario disadvantage firms in other Canadian provinces that could sell into their markets. Content requirements could be framed so as to broadly benefit Canadian production as opposed to targeting exclusively in-province production, though it should be noted that Ontario’s domestic content requirements are currently being appealed internationally through the WTO. Specific interprovincial barriers include a regulatory vacuum on ownership of geothermal resources and the lack of key infrastructure such as interprovincial transmission capacity.

Governments should support the development of low-carbon thermal energy and electricity sources to limit the “carbon exposure” of key sectors. Of particular concern are Canada’s energy-intensive tradeexposed (EITE) sectors. Addressing the carbon exposure of these sectors represents an opportunity for domestic LCGS innovation. However, government support for LCGS innovation, such as we discussed above, combined with flexible and adaptive regulatory and environmental approval frameworks (and in particular, provincial frameworks) are necessary. Regulators tend to be inherently risk-averse, and new technologies, new approaches, and new fuels can present evaluation challenges. New proposals and approval applications in heavy industry also frequently generate substantial interest from local community members, presenting a need for significant communications efforts and community engagement. Governments can actively promote positive innovation by developing approval frameworks that encourage demonstration projects and the generation of data required for technology verification and further development.

FOSTERING TALENT AND SKILLS DEVELOPMENT

Our collective talent can be a driver of a low-carbon transition, but a lack of preparation can be a barrier. A low-carbon transition will cause a shift in demand for certain occupations, may result in the emergence of new occupations, and may require existing occupations to take on new skillsets. However, issues of labour shortages and skills gaps can curtail growth and cause structural unemployment. Globally, the International Labour Organization (ILO) states that present shortages are already hindering a global low-carbon transition.120

Federal and provincial governments must increase their knowledge of the human resource requirements of LCGS sectors and of economy-wide changes to employment resulting from a low-carbon transition. Canada’s ability to prepare for the low-carbon transition is currently hindered by gaps in knowledge, including the absence of official statistics on skills requirements and employment levels in LCGS sectors and related occupations. Without such understanding, developing, coordinating and deploying training and employment programs to facilitate low-carbon growth is difficult for all labour market actors.

ECO Canada, an industry-led environmental-careers organization, reports that there is a need for better information on the skills and employment needs of Canada’s growing green economy.121 Governments must lay the groundwork by generating employment and economic statistics for current and emerging LCGS sectors.

Federal and provincial governments need to collaborate on the design and implementation of a coordinated jobs policy that explicitly addresses LCGS sector needs in the context of broader economic development objectives and competing demands for human resources. Energy and climate policies must be linked with job creation and skills development strategies. There is sufficient information to move forward and encourage training for skills Canada knows will be in demand. Other major industrialized nations, as well as many emerging economies, have moved forward with aggressive low-carbon growth plans, many of which are linked to job creation and skills strategies.122 Coherence between these two priorities is the key to a successful transition, as the ILO noted in its foundational report comparing 21 such strategies. 123 The lack of such a strategy risks losing economic and employment opportunities associated with the low-carbon economy. Science, technology, engineering, and math — the so-called STEM skills — form the core skillsets upon which many more detailed occupations are formed. These skillsets have been in high demand in the past, are presently, and will continue to be in the future. These skills are also essential in building a leading-edge, innovative low-carbon economy. The most recent C-Suite Surveym acknowledges that the hardest jobs to fill are those that require STEM skills.124 Skills for efficient and low-carbon buildings will also be in very high demand. Governments should ensure that the scale of training for low-carbon trades exists, is accessible, and meets high standards.

[d] Some provinces such as Québec, Ontario, and British Columbia are taking a lead in this realm with the introduction of legislation and programs that are clearly supportive of and aimed at developing robust, prosperous, cleantech sectors.

[e] SDTC in particular has established a strong track record of screening projects and financing those with strong potential and manageable risk profiles.

[f] Innovation clusters (also called innovation ecosystems) consist of interactions between business, universities, and government in a manner that provides the necessary ingredients to foster innovation (University of Alberta 2011), and “support and sustain the creation and growth of new ventures” (Council of Canadian Academies 2009). Several clusters supporting cleantech innovation exist in Canada, including MaRS and Écotech Québec.

[g] See Hansen 2006 and Metz et al. 2007 for discussions on what constitutes dangerous climate change and why.

[h] The discussion of future low-carbon investment requirements in Canada draws from a research report prepared for the NRT by Navius Research Inc. (Navius Research Inc. 2012), available upon request.

[i] In its analysis for the 2010 SDTC Cleantech Growth and Go-To-Market Report, the Russell Mitchell Group presents a benchmark for the maturation timeline for highgrowth technology-based companies. The authors suggest that high-growth technology-based companies achieve revenues of $100 million within 10 years of start-up. Based on survey results, they estimate that Canadian cleantech companies take between 10 and 15 years to reach this revenue benchmark (Sustainable Development Technology Canada and Russell Mitchell Group 2010).

[j] A similar concept for broader science and technology R&D collaboration already exists in the form of ISTP (International Science and Technology Partnerships) Canada which is intended to stimulate early-stage partnership development, facilitate the creation of partnerships between Canadian companies and research organizations and their international counterparts, and invest in cooperative R&D projects with high commercial potential (International Science and Technology Partnerships Canada Inc. 2009).

[k] For example, see Carrington and Vaughan 2011; Conway-Smith 2011.

[l] For more detail, see: United Nations Environment Programme 2012b.

[m] The C-Suite Survey is a quarterly opinion survey commissioned by Business News Network and The Global and Mail. It is aimed at chief executive, chief financial, and chief operating officers of Canada’s largest 1000 companies. (The Gandalf Group 2011).

[100] OECD 2011d

[101] Public Policy Forum 2011b; Bell and Weis 2009

[102] Analytica Advisors 2011

[103] International Energy Agency 2011a

[104] Statistics Canada 2012d; as cited in Navius Research Inc. 2012

[105] Government of Canada 2012b

[106] Accenture 2011

[107] Accenture 2011

[108] Accenture 2011

[109] Accenture 2011

[110] Accenture 2011

[111] Accenture 2011

[112] Accenture 2011

[113] The Confederation of British Industries 2011

[114] Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change et al. 2011

[115] Parhelion and Standard & Poor’s 2010

[116] Justice 2009

[117] Accenture 2011

[118] Environmental Commissioner of Ontario 2010

[119] Cosbey, Stiebert, and Dion 2012

[120] International Labour Office 2011c

[121] ECO Canada 2012

[122] International Labour Office 2011b

[123] International Labour Office 2011b

[124] The Gandalf Group 2012