Parallel Paths – 5.3 The NRTEE Transitional Policy Option

The NRTEE suggests that the fourth option – a contingent pricing approach – could provide the foundation for an effective strategy to manage current competitiveness risks in Canada-U.S. climate policy and achieve a reasonable and realistic balance between environmental and economic objectives.

In this section, we develop the key elements of a possible strategy for Canada to move forward now, building on our analysis of a contingent pricing tool and other policy ideas explored in the previous chapter. This Transitional Policy Option offers an innovative new approach that would allow Canada to drive investment in low-carbon technologies and to achieve real emission reductions. The option fosters policy certainty in Canada even in the wake of uncertainty in U.S. policy direction. It leaves Canada free to adjust and harmonize future climate policy elements with the U.S. as its own policy comes online, setting up Canada for eventual linkage with a U.S. system.

The Transitional Policy Option contains the following four elements:

1 // Contingent carbon pricing — to establish a price collar that limits the Canadian carbon price to be no more than $30 / tonne CO2e higher than the price in the U.S.;

2 // A national cap-and-trade system — with auctioning of permits and revenue recycling to cap emissions and address regional and sectoral concerns.

3 // Limited international permits and domestic offsets — to keep domestic carbon prices lower for Canadian firms, thus maintaining competitiveness, and further harmonizing with U.S. policy direction ; and

4 // Technology fund — to keep domestic carbon prices lower for Canadian firms, align carbon prices close to those in the U.S., and stimulate investment in needed emission reductions technologies.

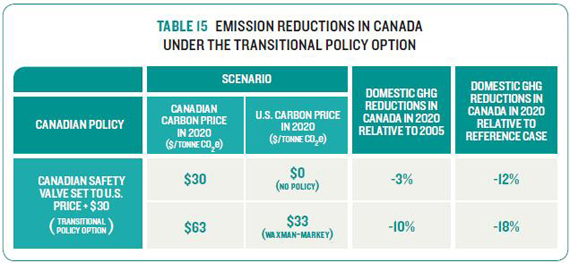

To assess the NRTEE’s transitional policy option, we explored modelling scenarios that consider implications both if Canada faces continued uncertain U.S. climate policy or if the U.S. implements a Waxman-Markey-like policy with an economy-wide carbon price through a cap-and-trade system, and extensive offsets that would likely keep the carbon price around $30 / tonne CO2e by 2020. We modelled U.S. policy in these scenarios as a stylized version of Waxman-Markey, as it is broadly representative as a real legislated policy for the U.S. Analyses of proposals such as Waxman-Markey, Kerry-Boxer and Kerry- Lieberman all impose comparable carbon prices of around $30/tonne CO2e and are thus broadly consistent with our representative scenario.

We find that a price differential of $30 / tonne above the U.S. price by 2020 would allow for real emission reductions in Canada while limiting competitiveness implications. This contingent carbon pricing differential acts as a price collar, placing a ceiling on just how high Canadian carbon prices rise. It results in actual emission reductions, which would be a first step down the road to long-term reductions, whether the U.S. implements policy or not. In economic terms, the price differential provides greater price certainty by guaranteeing the carbon price won’t rise too much above the U.S. price, but at the cost of quantity certainty in terms of achieving targeted emission reductions. The approach also allows Canada to pilot the institutions required to implement an operational cap-and trade system for eventual linkage with the United States.

If the U.S fails to implement a cap-and-trade system — and imposes no carbon price — Canada can implement its own modest but initial carbon pricing policy with a maximum carbon price of $30. If the U.S. implements policy as well, the Canadian carbon price can become more stringent to drive more emission reductions, though never become too much out of step with the U.S, thereby maintaining economic competitiveness. The price collar acts to moderate the risks of adverse economic outcomes both nationally and to specific sectors and regions.

NATIONAL CAP-AND-TRADE SYSTEM

The contingent carbon pricing policy is given effect through an economy-wide national cap-and-trade system. A continental or harmonized carbon trading system is stated federal government policy. Several provinces have been actively developing an integrated trading regime with several U.S. states under the Western Climate Initiative. Continuing progress on this front makes sense. As recommended in the NRTEE’s Achieving 2050 report, this would put in place a market-based instrument to allow for the buying and selling of carbon pollution permits by regulated firms or industry sectors. This would generate revenue for government that could be recycled back to firms or provinces to address local competitiveness or economic concerns. One approach would be to allocate some free emissions permits to emissions-intensive and trade-exposed industry based on historical emissions intensity. Tracking how the U.S. is considering this approach and whether similar allocations should be made-in-Canada would add a further level of harmonization. Alternatively, permits could be auctioned and substantial revenue recycled to reducing taxes. Free allocations or recycling to corporate taxes can address regional impacts and prevent revenue from being transferred from capital and emissions-intensive Alberta and Saskatchewan in an inequitable way.71

As the NRTEE proposed in Achieving 2050, targeted regulations can complement a capand- trade system by expanding coverage of the program to include emissions difficult to include under a cap-and-trade system and by addressing market barriers for technological innovation and deployment to enable the carbon price to incent low-carbon technology. Canada could continue to harmonize with the U.S. on regulatory mechanisms as it has on vehicle emission standards.

ACCESS TO INTERNATIONAL PERMITS AND DOMESTIC OFFSETS

Since international reductions will likely be available at a relatively lower cost than in Canada, allowing firms to comply with a cap through international permits would allow greater global emission reductions as a result of Canadian policy, without the very high carbon price required under a Canada-only approach. If the international carbon permits purchased are credible, this approach would not reduce the environmental credibility of the policy, though other concerns about equity issues and perverse effects of offset funding in the developing world could emerge. However, investment in international reductions would result in financial flows out of Canada, representing lost opportunity to invest in reductions within Canada.

Similarly, domestic offsets from Canadian forestry and agriculture could provide lowercost reductions if complementary regulations cannot be used to drive reductions in these sectors. Indeed, the low carbon price expected in the U.S. under policies such as the Waxman- Markey bill is largely due to expectations that a large share of U.S. emission reductions will come from land-use changes that increase forests’ ability to act as a carbon sink. Again, this approach will constrain costs while still achieving emission reductions, as long as institutional capacity exists to ensure that the land-use changes are permanent and would not have happened without the offset investment. Nevertheless, if these cost containment mechanisms are available to American firms, they should also be available to Canadian firms as part of a harmonized policy approach between the two countries.

Use of both international and domestic offsets would be limited to ensure that the bulk of compliance would be achieved through domestic abatement or investment in low-carbon technologies in Canada. A finite percentage of compliance for Canadian firms would be allowed through these mechanisms.72

TECHNOLOGY FUND

As part of contingent pricing, Canada could set a maximum carbon price through a safety valve such as a technology fund. Firms could purchase additional emissions permits from the government at a fixed price (set at no more than $30 above the U.S. carbon price). The government revenue generated from these purchases would be deposited into a new, national Low-Carbon Technology Fund devoted to the development and deployment of low-carbon technologies. NRTEE analysis suggests that the fund would generate revenue of around $0.5 billion in 2020 if both countries implemented policy, and around $2.0 billion if only Canada implemented policy. Table 16 below compares the approximate levels of revenue that could be expected from these two scenarios. To put these values in context, in Achieving 2050, the NRTEE found that to achieve Canadian targets, additional investment in low-carbon technologies as a result of policy would have to reach around $2.2 billion a year, so clearly some progress would be made now, better positioning Canada for the future.

[71] In our modelling of the Transitional Policy Option, we applied a system of full auction with full recycling back to income and corporate tax (50% to each). Our scenarios (as presented in Chapter 4) illustrate that substantial recycling to corporate taxes significantly reduces regional economic impacts. Similar distributional outcomes could be achieved with different approaches to providing allocations for free based on some combination of output or emissions intensity.

[72] In our modelling analysis of the Transitional Policy Option, international permits are limited to 25% of compliance, and only domestic landfill gas offsets are included.

[73] The revenue to be generated may vary given that the costs of abatement and methods by which firms will comply with a policy are unknown However, these values are estimated for the Alberta and Turning the Corner funds based on assumptions from published material on the policies.