3.0 An Adaptation Dashboard for Business Success – Facing the Elements

Business success in a changing climate is about foresight and flexibility. It’s also about making smart decisions under uncertainty. Lessons from NRT case studies and other sources show how businesses are taking action.

Despite a strong theoretical case for adaptation, preparing for future impacts is not common practice. Even getting started can be overwhelming for some, especially when “they don’t know what they don’t know.” The challenge is particularly acute for small- and medium-sized businesses with limited resources to direct to the issue. So, what steps can and should Canadian businesses take to reduce risks and seize opportunities in a changing climate? What are the benefits? This chapter showcases a framework for business success in a changing climate, sourced mainly from NRT’s case study research.

Despite a strong theoretical case for adaptation, preparing for future impacts is not common practice. Even getting started can be overwhelming for some, especially when “they don’t know what they don’t know.” The challenge is particularly acute for small- and medium-sized businesses with limited resources to direct to the issue. So, what steps can and should Canadian businesses take to reduce risks and seize opportunities in a changing climate? What are the benefits? This chapter showcases a framework for business success in a changing climate, sourced mainly from NRT’s case study research.

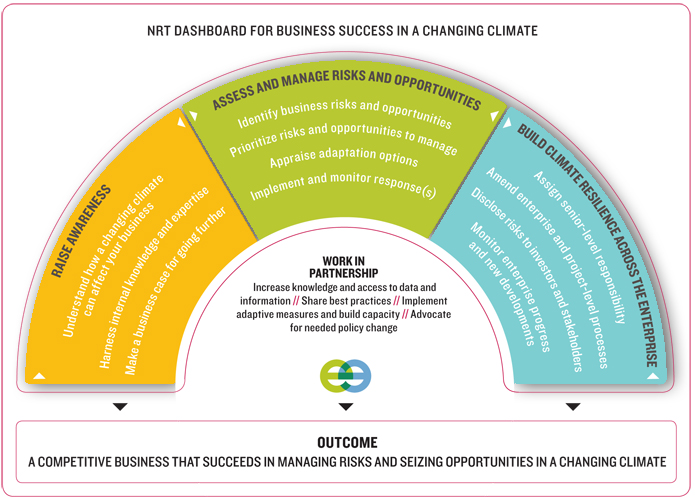

3.1 THE NRT DASHBOARD

FIGURE 3

In a changing climate, businesses that routinely incorporate climate change impacts and adaptation in major investment decisions and in decisions with long-term consequences will be better off than their competitors. The figure above sets out a dashboard for business success in a changing climate broken down into three phases. Because the range of changes in climatic variables and the resulting physical impacts (and in turn the range of possible business impacts) is broad, businesses first need to understand how shifts in climate conditions — both average and extreme — affect them. To prioritize actions, businesses move on to assessing specific risks and opportunities, as well as options to manage them, and then on to implementation. A further phase is then to integrate climate resilience across the — from the boardroom to the copy room.

The dashboard is not prescriptive. The “right” strategy for a firm will depend on risk exposure and a host of firm-specific factors, including capacity, risk tolerance, and current knowledge of problems and solutions. Some businesses may undertake all the steps laid out below, others will instead focus on a few.

// Understand how a changing climate can affect your business

// Harness internal knowledge and expertise

// Make a business case for going further

ASSESS AND MANAGE RISKS AND OPPORTUNITIES

// Identify business risks and opportunities

// Prioritize risks and opportunities to manage

// Appraise adaptation options

// Implement and monitor response(s)

BUILD CLIMATE RESILIENCE ACROSS THE ENTERPRISE

// Assign senior-level responsibility

// Amend enterprise and project-level processes

// Disclose risks to investors and stakeholders

// Monitor enterprise progress and new developments

// Increase knowledge and access to data and information

// Implement adaptive measures and build capacity

// Advocate for needed policy change

3.2 RAISE AWARENESS

Understand how a changing climate can affect your business

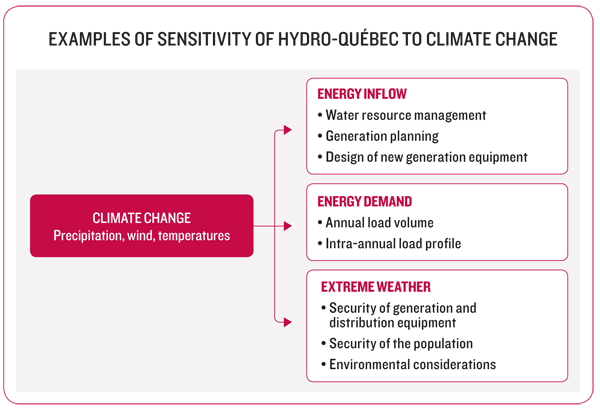

Several aspects of business are sensitive to changes in climate conditions and other environmental factors influenced by climate. It’s important to map out just what those aspects could be A high-level scan of regional climate projections and research on climate change impacts published by governments, research organizations, and others can help identify the climatic shifts and resulting impacts (both positive and negative) anticipated in regions where the business operates.[j]

FIGURE 4

The scan should look beyond the “factory walls,” to encompass the regions where upstream suppliers and downstream customers are based, as well as the corridors through which products and services move.

Firms should look backward to identify the business impacts of previous climate-related events likely to increase in frequency and intensity in a changing climate (e.g., storms, droughts, unusually hot or unusually cold seasons) and create an inventory of impacts, responses deployed, and their effectiveness.

Harness internal knowledge and expertise

Coming up with a business response to climate change has tended to be a task, at least initially, for environmental sustainability or corporate social responsibility officers. However, climate change impacts can have far-reaching consequences for businesses and therefore for employees across operations, legal, and finance units, to name a few. A changing climate could pose operational risks to the business, by, for example, increasing the scarcity of a resource that is an input to production. Legal liability risks could arise from climate-related damages to local communities. Gradual changes in climate variables and the physical impacts that flow from them can affect a business’s long-term financial performance and, if that’s the case, merit disclosure to investors.

By pooling knowledge and sharing expertise across business units, firms can develop a good picture of the links between climate change impacts and business objectives. Formal working groups, focused workshops, and information sharing through web-based platforms, are all examples of mechanisms to bring together a firm’s intellectual capital. Cultivating ownership of the adaptation challenge and developing a shared “climate change story” are additional benefits of prompt engagement across the organization. An early step is to ensure all participants have a solid understanding of the difference between adaptation and GHG emissions mitigation.36

Buy-in at senior levels can make or break an initiative that aims to build business capacity to do things differently. Early engagement of senior management can add perspective to the discussion and lead to issue-championing around the executive and board tables.

Make a business case for going further

The case for allocating scarce human and financial resources to assessing and managing risks and opportunities of climate change can be a tough sell: the perception looms large that up-front costs are high and payback is uncertain and long-term.

Articulating a business case, therefore, is a key early step. This is easier to do for businesses that have suffered recent, costly climate-related damages, particularly if brand and reputation issues were at stake. Businesses interested in taking a proactive stance can also cite experiences of competitors that have taken a hit due to recent extreme weather events.[l]

Firms can also use the generic business case presented in Chapter 2 to develop their own. It should identify vulnerabilities to current climate-related events, highlight the direct impacts the business could face due to inevitable climate change already underway and from future climate change, consider stakeholder positions shaping business reputation and licence to operate, point to the immediate and long-term benefits of investments in adaptation, show that there are simple and inexpensive ways to adapt, and finally highlight commercial opportunities in adaptation that first-movers can exploit.

Prompted by a study on the impacts of climate change on investment drivers, a group of investors asked an international extractive company about its climate risk-management practices. In turn, this led the extractive company to seek assistance from a specialized climate risk consultancy to undertake a high-level risk assessment, develop a strategic framework, and estimate the costs of climate change risks out to the 2020s and 2050s.38

3.3 Assess and manage risks and opportunities

Identify business risks and opportunities

The point of phase one is to gather basic information and intelligence on the possible implications of climate change for the business and to start building capacity and buy-in across the enterprise. This second phase involves a detailed assessment of the risks and opportunities for the business, and organizing this assessment along the following five areas is a good place to start.[m] Firms can also scope their assessment down to a specific component of the business’s operations that is critical to the bottom line or to a specific geographic site, for example. Starting small has the advantage of learning-by-doing without huge outlays in resources.39

// SITE CONDITIONS, PHYSICAL ASSETS, AND INFRASTRUCTURE. Climate change impacts could positively or negatively affect the suitability and performance of operation sites, physical assets, and privately owned infrastructure. For example, permafrost degradation could increase the operating costs of northern resource extraction sites. Machinery and buildings could underperform in warmer and wetter conditions. More volatile weather and more frequent freeze-thaw cycles may alter infrastructure repair and upgrade schedules.

// PROCESSES AND WORKFORCE. Climate conditions and climate hazards can influence industrial processes and workforce safety and productivity. Rising stream temperatures will hinder energy producers’ efforts to cool generation plants. Construction businesses, however, could benefit from a longer ground-ice free season. Storms and other weather extremes contribute to employee absenteeism. In a changing climate, outdoor workers could be less exposed to cold-weather hazards but more exposed to excessive heat.

// RAW MATERIALS, SUPPLY CHAINS, AND LOGISTICS. Rising numbers of extreme weather events and gradual shifts in climate will create winners and losers by disrupting flows of raw materials (like water and fibre) and products and services across supply chains. In a global economy, climate-related events abroad cause ripple effects domestically: a hurricane along the U.S. Eastern Seaboard can shut down a supplier’s plant in Southern Ontario. Commercial opportunities are also apparent: Canadian logistics businesses can move quickly to become leading providers of supply chain management solutions.

// PRODUCTS, SERVICES, AND MARKETS. A changing climate and responses to it could shift demand for the products and services the business provides.[n] A rise in demand for engineering services and changing patterns of summer and winter demand for power are just two examples.

// REGULATORY RISKS, CHANGING STANDARDS, AND BUSINESS REPUTATION. As awareness of climate change impacts becomes widespread, businesses in highly regulated sectors, such as energy and telecommunications, will see increased demand for assessment and disclosure of risks from climate change and actions to manage them. Governments, multi-lateral agencies, and professional bodies may also create new regulation and performance standards to this effect, tapping into the expertise of engineers and other professionals. Businesses’ reputations could suffer if stakeholders perceive them to be lagging or negligent on the issue. This provides a good incentive for businesses to work with stakeholders on shared adaptation challenges.

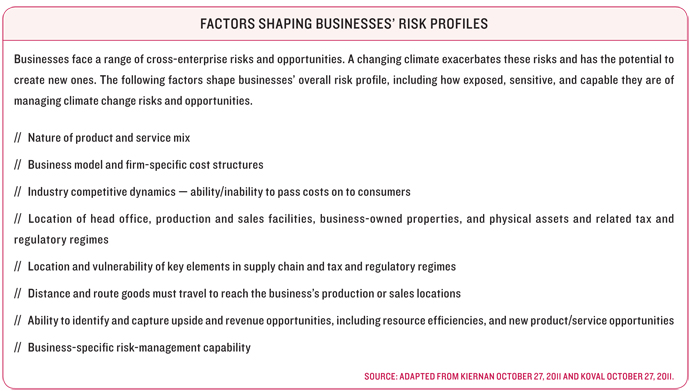

Prioritize risks and opportunities to manage

After completing a high-level scan, a business can then triage the long list of risks and opportunities into those that demand immediate action, should simply be monitored, or can be put aside. Risk is a function of the probability of an event occurring and the magnitude of the consequence should it occur. Exposure to the impacts of climate change is rarely — if ever — the only or most important factor determining a business’s overall risk profile (see Box 1). A business’ overall risk profile should guide the extent to which climate change risks require specific managed responses.

BOX 1

To prioritize risks and opportunities to act on, businesses can assess each in turn using pre-defined criteria covering the following dimensions:

// FINANCIAL RISK: To what extent could climate change risk or opportunity threaten or enhance overall business value? Do previous experiences within the business or for competitors show the financial implications of the risk or opportunity?

// TIMING: When are climate change impacts expected to materialize? What kind of lead time could the response require? Both questions are relevant here. For example, in renewing its forest management plan, a business managing large forested areas may prioritize early investments in adaptive measures because a given tree species could cope well with changing climate conditions over the next two decades but not over the 80 years or so that trees take to mature.

// ALIGNMENT WITH CORPORATE VALUES: What risks can the business absorb? At what point do they become unacceptable? Criteria like risk to health and safety, business reputation, and share value are among those that can help prioritize both upside and downside risks to manage.

// PROPORTIONALITY: Businesses face a range of risks, some completely unrelated to climate. The degree of effort to manage risks either created or exacerbated by the impacts of climate change should be comparable to other risks being actively managed.40

// KNOWLEDGE: The precise magnitude, timing, and location of climate change impacts will never be certain. But that’s not a valid reason to ignore climate change risk and defer action. Use the best available information to treat uncertainty about climate change and its impacts like any number of sources of business uncertainty (see Box 2).

BOX 2

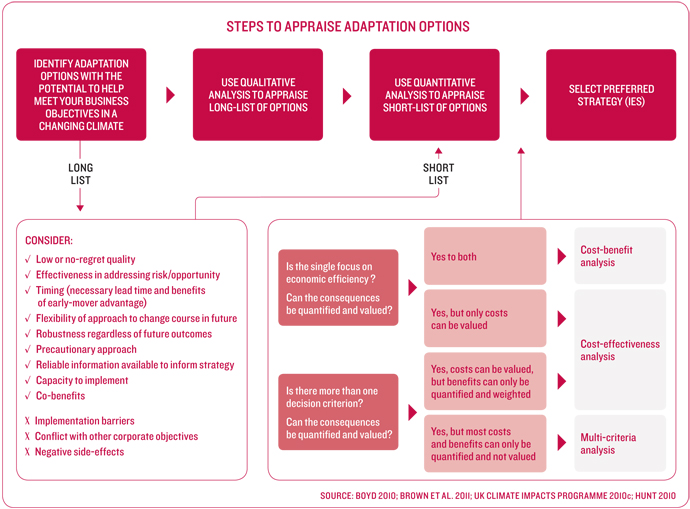

Appraise adaptation options

Prioritizing risks and opportunities to manage gives way to deciding what to do about them. In the appraisal process, options to both manage specific climate-related risks and build system resilience warrant attention. Throughout this appraisal, think beyond business boundaries, collaborating with infrastructure providers, suppliers, and others in the value chain. Vulnerability can be reduced by transferring or spreading risk, reducing risk exposure, and avoiding risk. Other options are accepting the loss and exploiting new opportunities.43

In choosing the most appropriate responses, businesses may benefit from the approach and criteria set out in Figure 5. Since we will never have complete information about the precise magnitude and timing of future climate change or its impacts at a given location, instead of pursuing “optimal” solutions, businesses subject to climate change risk should adopt strategies that minimize the cost of being wrong.44

FIGURE 5

In some cases postponing action to study the issue and try to narrow uncertainties makes sense, all the while monitoring for shifts in risk profiles.45

Implement and monitor response(s)

Key elements of an implementation plan include roles and responsibilities, resource requirements, possible implementation challenges and corresponding ways to address them, links to other business activities, tasks and timelines, and a stakeholder engagement and communication strategy.47

Implementation goes hand in hand with monitoring and evaluation. This means establishing key performance indicators, success criteria, procedures for collecting data, as well as mapping the process in a monitoring and evaluation strategy.48 Gathering baseline data is a key step in monitoring and evaluation. Evaluations conducted midstream not only flag needed course corrections but also inform future planning decisions,49 provided findings reach the right people. The results of some adaptive measures may take time to materialize. Plus, responses taken to adapt to climate change are often inseparable from good risk management, posing challenges to linking the implementation of adaptive measures to particular outcomes. In such cases it makes sense to use process indicators to assess performance. For example, monitoring can be used to evaluate whether and how corporate governance systems facilitate assessment, reporting, and management of risks and opportunities from a changing climate.

3.4 BUILD CLIMATE RESILIENCE ACROSS THE ENTERPRISE

Assign senior-level responsibility

Managing the risks and opportunities of climate change is a corporate governance issue. Senior leadership is an essential ingredient.50

Assigning responsibility for building climate resilience at senior levels sends a message to the whole business that the issue is a priority. Promoting risk awareness across the enterprise, strengthening coherence among businesses’ sustainability and financial units, and creating a mechanism for adaptation to efficiently infuse senior-level discussions and planning exercises are just a few possible benefits of this. Several businesses have a corporate climate change strategy. Including adaptation as part of it clarifies the corporate position to staff, articulating the need and rationale for integrating adaptation thinking across the business model.

Amend enterprise and project-level processes

Amending business management systems to integrate climate change risks is an effective and efficient way to hard-wire adaptation into the way firms do business.51 Firms already rely on a number of management systems that cut across business functions, emphasize continuous improvement, and are relevant to climate change adaptation. These include enterprise risk management, business continuity planning, quality assurance, and environmental management systems.[o] But the scope of the climate change adaptation challenge and coverage of the existing management systems is not a perfect match and some amendments are necessary. For example, a quality management system is unlikely to cover the risk of more costly or unavailable insurance posed by climate change.

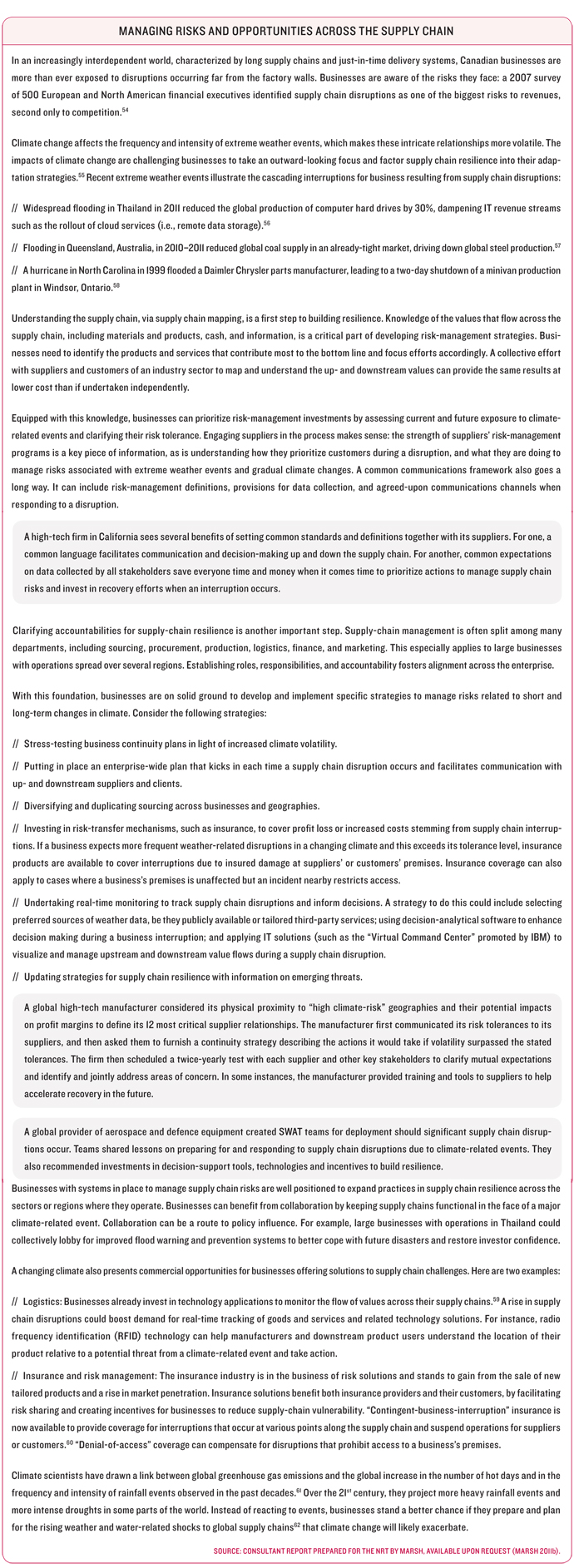

Taking stock of enterprise-wide processes and guidelines that merit adjustments in light of climate change is a good place to start. What, if anything, needs to be done so adaptation thinking factors into key decision points, including siting decisions, long-term planning, and capital asset plans?52 Are contracting and procurement processes sufficiently flexible to accommodate disruptions in raw material availability in a changing climate? Should infrastructure projects require additional and explicit consideration of future climate conditions, and at what stages? How can relationships with suppliers and customers foster resilience across the supply chain (see Box 3)?

BOX 3

Disclose risks to investors and stakeholders

Quality disclosure is the backbone of strong capital markets and stakeholder confidence. By law, publicly traded companies must report material risks and associated management actions to investors under continuous disclosure obligations. In 2010, the Canadian Securities Administrators issued guidance to clarify how environmental risks, including climate change, may be material and how this disclosure should be presented.63 According to this guidance and advice published by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants, businesses should do the following:

// Provide business-specific instead of boilerplate disclosure of material risks.

// Disclose existing and planned risk management, adaptation, and mitigation strategies along with expected implementation costs.

// Employ robust controls and procedures to identify and manage material risks.

// Not assume information furnished on their website or through voluntary reporting initiatives replaces the need to disclose material risks in their financial filings. Consistency is important.

// Consult several sources to identify material information for inclusion in annual securities filings. These include CDP survey responses (the business’s own response as well as peer businesses’ responses), industry research papers (for sector-based impacts), corporate social responsibility or sustainability reports, enterprise risk-management reports, board minutes, and strategic statements and plans.64

“Best practices” in disclosing risks from the impacts of climate change and related adaptive measures in financial filings do not yet exist, but monitoring disclosure practices of industry sector peers helps anticipate increased demand for enhanced quantity and quality of disclosure from investors and stakeholders.

In its 2010 securities filings, the Greater Toronto Airports Authority (GTAA) noted that climate change may lead to more severe weather, creating flooding risk for airports. The GTAA is spending roughly $100,000 to identify improvements and adjustments in operational practices to prevent storm flooding.65

Because of the many similarities between Canadian and U.S. securities reporting requirements, an example of “good” disclosure of physical risks from climate change by an American issuer is worth noting.

In its 2009 filings, Chiquita Brands International, Inc. reported that “unfavorable growing conditions… may result in lower sales volume and… increased costs due to expenditures for additional agricultural techniques or agrichemicals, the repair of infrastructure, and the replanting of damaged or destroyed crops.” It then reported financial impacts related to a flooding event in 2008, which allowed them to quantify the scale of the risk facing the company.66

Monitor enterprise progress and new developments

Leading-edge businesses stay attuned to advancements in climate science and adaptation research and scan for new risks and opportunities on the horizon. As the landscape changes, businesses then factor new information into their ongoing process of assessing and managing risks (i.e., phase two in the dashboard). These businesses also step back from the micro-assessment of each individual strategy and take an enterprise-wide view of their progress in adapting to the risks and opportunities of a changing climate.

Anglian Water, a large private water utility in the U.K., views climate change as among the greatest risks to the business due to the expected reduction in summer rainfall and the already dry nature of the region. It has put in place several adaptive measures to secure alternative supplies and to promote conservation among its customers. The company relies on asset performance indicators to monitor its climate resilience. Anglian Water believes that a flexible approach to adaptation is critical, and plans to use its ongoing review process to identify new risks and adaptive responses over time.67

The U.K.’s Thames tidal floodplain is home to 1.25 million residents, £200 billion in current property value, and a network of flood defence measures including the Thames Barrier. The U.K. Environment Agency held consultations and conducted in-depth analysis to identify flood risks out to 2100, taking into account anticipated climate change and its consequences on sea level, high tide level, and wave height. Because of the degree of uncertainty about changes in the far future, the Thames Estuary 2100 Plan is flexible and iterative: reviews against a set of key indicators every 10 years inform flood management actions, including selecting, adjusting, accelerating, or postponing action.68

3.5 Work in partnership

Each of the three phases in our dashboard can include working in partnership. Some good ideas how are set out below.

Increase knowledge and access to data and information

Working in partnership with like-minded businesses is efficient: businesses can gain valuable knowledge and information at low cost. Businesses in a same industry sector are often sensitive to similar types of climate change impacts. By working through an industry association, for example, businesses can leverage resources to undertake a sectoral risk and opportunity assessment or to come up with key indicators to measure adaptation performance. Such partnerships could work on a regional basis as well, in this case involving a number of industry sectors and leveraging resources to study local impacts of climate change.

Outsourcing specific knowledge gaps, tool development, or other services to external experts is also an option to consider for all phases of the process. A key question is how much to rely on external advisors instead of investing in building internal business capacity. Businesses can tap into knowledge through consulting firms, academics, regional climate service centres, and other businesses confronting the same issues.

Share best practices

In this emerging field, sharing best practices can only help accelerate action and reduce transaction costs. Industry associations can create forums for this information-sharing to occur, particularly when competition among businesses is limited (e.g., where regional monopolies exist). Professional bodies and trade associations have a role to play in disseminating best practices by integrating climate change adaptation into standard professional guidance.

The International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC) is raising the profile of climate change among its members. FIDIC issued a final draft policy on climate change in October 2011, stating that, because of changing climate conditions, engineers should be careful in relying on historic design conditions, also emphasizing the need for a heightened level of care and innovation in providing design services.69

The Canadian Electricity Association (CEA) held a joint workshop between its Generation Council and Sustainable Electricity Steering Committee in spring 2011 to explore climate change impacts and adaptation issues for the sector. In the two-day workshop, the 12 participating utilities learned about drivers for adapting to climate change, including insurance, legal liability, and risks to infrastructure; they also shared best practices, challenges, and lessons learned. This workshop launched CEA’s engagement with its members to help advance climate resilience across the electricity sector.70

Implement adaptive measures and build capacity

Firm-level action can accomplish a lot; however, implementing adaptation strategies can require engagement by others. Collaboration to reduce risks across a supply chain, to manage shared access to a limited resource, to build community resilience, and to enhance ecosystem resilience are a few examples.

Industries like insurance, engineering, and construction could become providers of adaptation solutions, and may want to work in partnership to highlight the role they can play to support adaptation.

Advocate for needed policy change

As the impacts of climate change intensify, policy and regulatory change is sure to follow. Businesses may find it advantageous to work collaboratively to engage with governments on the issue. Existing and future government policy frameworks have the potential to help or hinder industry’s progress in managing climate change risks and opportunities, and government agencies are starting to use an adaptation lens in policy and program development and review.p In some cases, new policies that mandate assessment of climate change risk or specific management actions among the private sector may also be necessary. Being at the table as policies are adjusted or new ones created is key.

Intact Financial Corporation, a major insurer operating in Canada, teamed up with the University of Waterloo to support research and policy action on six climate change adaptation challenges for Canada: agriculture, biodiversity, city infrastructure, First Nations, freshwater resources, and insurance. The project includes an outreach plan and through it, a commitment to engage policymakers, among others.71

3.6 Strategies for small-and mid-sized enterprises

Small businesses are an important source of jobs and economic prosperity in Canada. The 2.4 million SMEs[q] across the country contribute 45% of Canada’s gross domestic product,72 are responsible for 43% of Canadian exports,73 and employ 70% of Canada’s private sector workforce.74

Although about half of SMEs rank climate change among the top environmental issues for their business,75 capacity issues and short planning horizons can make it difficult to manage the risk and opportunities of a changing climate. Unlike larger businesses, SMEs often lack the resources to fund or undertake comprehensive studies, or to spend on preventative measures with large up-front costs. They may not have the management systems in place to integrate climate change information into business decisions. Furthermore, some SMEs may be inclined to dismiss the need to prepare for future climate change as too complex or too distant to consider.

Yet the ability of Canada’s SMEs to thrive in a changing climate and take advantage of new commercial opportunities is critically important. Results from one survey suggest that more than half of Canada’s SMEs are unprepared for an unexpected disruption to their business, and almost as many small business owners are unfamiliar with the concept of business continuity planning.76 That same survey noted that roughly 40% of small business owners had suffered a significant disruption to their business, with 80% of those disruptions lasting at least five days.

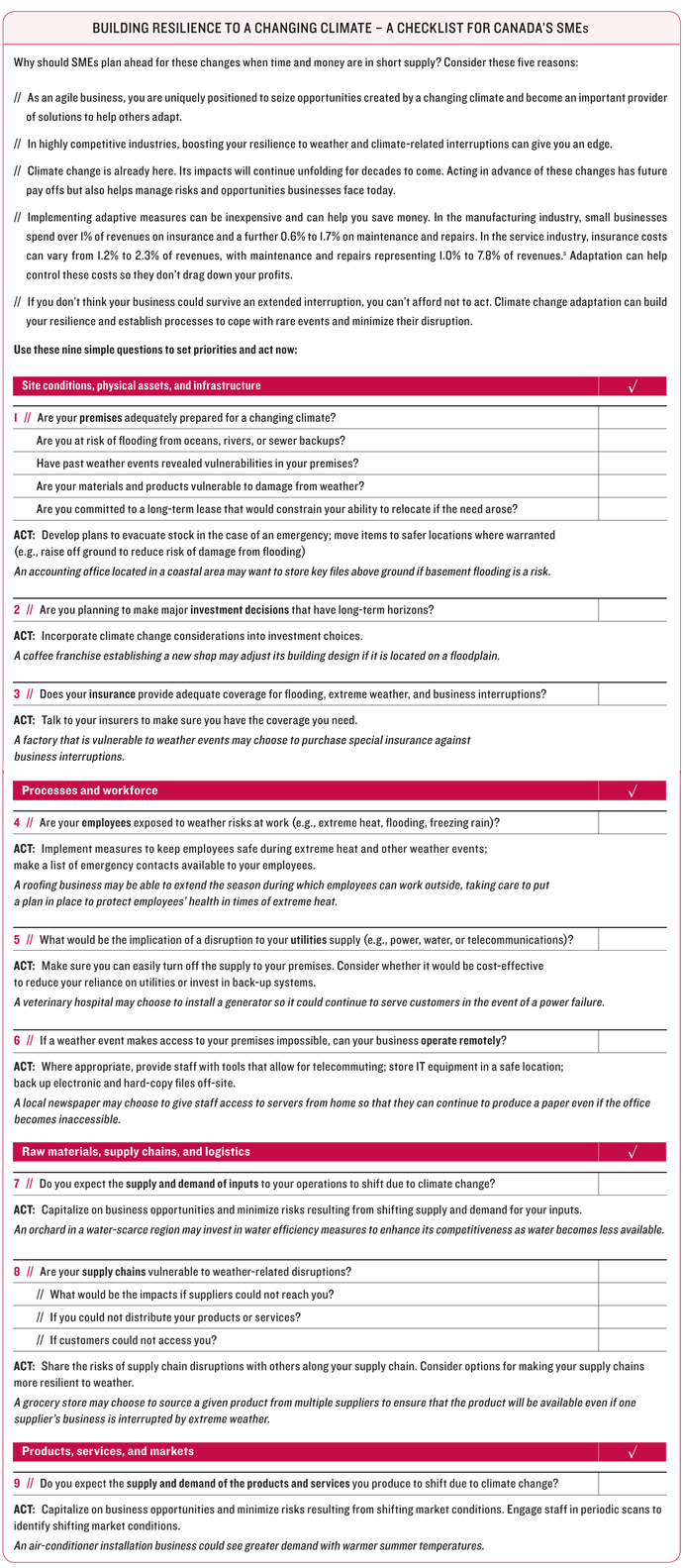

Because many of the tactics and strategies in this chapter are likely most relevant for large businesses, we dedicate Box 4 to SMEs.[r] It includes examples and questions designed to raise awareness of risks and opportunities from climate change and actions to address them.

BOX 4

[j] Appendix 6.2 lists resources to help with this step.

[k] Unless otherwise noted, all corporate examples are taken from NRT’s Facing the Elements: Building Business Resilience in a Changing Climate – Case Studies Report. The extracts in this Advisory Report are direct citations or paraphrasing.

[l] Although no single extreme weather event can be attributed to climate change, business impacts of extreme weather events highlight exposure to current climate conditions, which could grow as climate conditions shift.

[m] The categories we present more or less align with the themes covered in the U.K. Climate Impacts Programme’s risk assessments (UK Climate Impacts Program 2010c; Willows and Connell 2003). It also makes sense to use categories embedded in firms’ existing management systems.

[n] A changing climate, and related physical and social impacts, could very well trigger temporary or permanent displacement of people and communities away from places that have become inhospitable (UNEP 2012), potentially resulting in market dislocations.

[o] See Appendix 6.2 for links to some of these management systems.

[p] For example, British Columbia’s climate change adaptation strategy includes “make adaptation a part of government business” as one of its three strategies (British Columbia Ministry of Environment 2010).

[q] The Canadian Chamber of Commerce defines SMEs as companies “with less than 500 employees and annual sales of $30,000 to $5,000,000” (The Canadian Chamber of Commerce 2011). The number of SMEs is based on figures provided in Industry Canada 2011, and assumes “indeterminate” businesses are small.

[r] The tips in this section may be less applicable to the smallest SMEs, likely with the least resources to dedicate to the task.

[36] British Standards Institution 2011

[37] Willows and Connell 2003

[38] Amado December 15, 2011

[39] British Standards Institution 2011

[40] UK Climate Impacts Program 2010c

[41] Hallegate, Lecocq, and de Perthuis 2011

[42] Stirling 2010

[43] UK Climate Impacts Program 2010c

[44] Hallegate 2009 as cited in National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy 2010

[45] UK Climate Impacts Program 2010c

[46] Williams October 27, 2011

[47] UK Climate Impacts Program 2010c

[48] UK Climate Impacts Program 2010c

[49] Pringle 2011

[50] Cogan 2006

[51] British Standards Institution 2011

[52] UK Climate Impacts Program 2010c

[53] Odendahl October 27, 2011

[54] FM Global 2007

[55] CSR Asia 2010; Ernst & Young 2010

[56] Bilton 2011

[57] BBC 2011

[58] McGillivray 2000

[59] Zurich 2011

[60] Zurich 2011a

[61] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2011

[62] Carbon Disclosure Project 2012

[63] Canadian Securities Administrators 2010

[64] Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants 2008

[65] Greater Toronto Airports Authority 2011 as cited in Ceres and Climate Change Lawyers Network 2012

[66] Ceres 2011

[67] Anglian Water 2011

[68] Environment Agency 2009

[69] FIDIC 2011

[70] M. Turner, Canadian Electricity Association, personal communications, 2012

[71] Intact and University of Waterloo ND

[72] Canadian Federation of Independent Business 2011

[73] Industry Canada 2011a

[74] Statistics Canada 2005; as cited in Canadian Federation of Independent Business 2011

[75] Canadian Federation of Independent Business 2007

[76] Angus Reid Strategies 2009